The other question is about being in multigenerational households or large households, or if you’re in a shelter or single-room occupancy hotel with other roommates. With COVID-19, we had hotels, places where people could go to be able to isolate safely. That certainly should be part of the discussion about what the city offers for people living in very crowded circumstances to try to limit spread.

Secondly, we know that household transmission can occur. We are still trying to understand exactly how much, and thinking about the best ways to protect against that.

Are there some common themes about monkeypox, misinformation that you and the groups you’re working with are hearing on the regular? Something that just keeps popping up out there that just needs to be immediately debunked?

One of the biggest things that we need to keep addressing is the stigma associated with [monkeypox].

Certainly, while anybody could be affected with monkeypox, we are certainly seeing that this current outbreak is predominantly affecting men who have sex with men, gay, bisexual men and trans people. [We should continue] to mention that without making it sound like we are saying, “Oh, it’s a gay disease.” Continually mentioning who’s most infected helps us to direct resources to the community that is most affected, and most needs it.

I think there’s a lot of questions about how it’s transmitted. Really emphasizing right now that the predominant mode of transmission is close contact — mostly through sexual encounters — is important so that people know what their risk is.

It’s not to say that not everyone can be at risk, but we need to know who’s at highest risk right now. And so I think the questions about transmission, risk groups and addressing stigma are some of our top priorities.

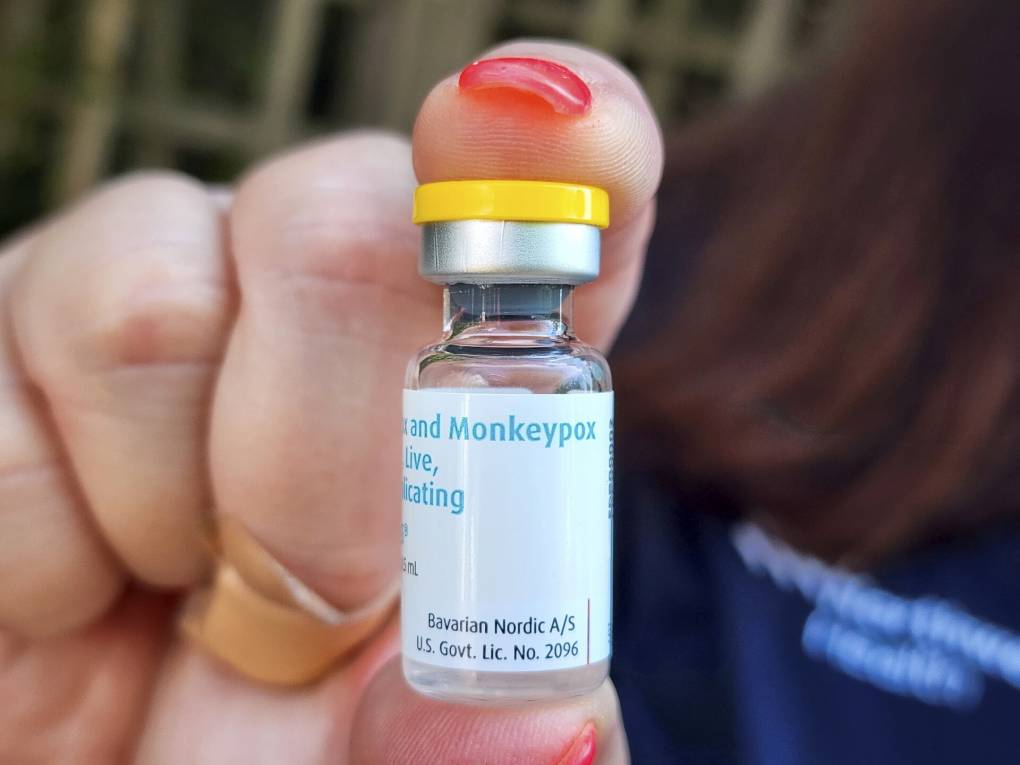

Now that the entire state of California is under a public health emergency from monkeypox, what difference does this make to expanding testing and vaccination?

Declaring this a public health emergency was the right thing to do so that we can have the resources to respond in a swift manner.

I will say, I have taken care of many patients with monkeypox. I’m one of the clinicians who is delivering TPOXX for the most severe cases, and seeing patients suffer with this disease — the pain that it causes — is heartbreaking.

We have tools to address this outbreak and we need to do it swiftly. This public health emergency is one of the pieces that will allow us to do it. We have a lot of work to do, especially in terms of addressing it equitably. But this is one component to get us there.