“Wait a minute…” All heads turned as a student, who only moments before was silently typing away at her computer, slowly rose from her seat, eyes locked on the screen in front of her. After what seemed like an entire minute of silence, she looked straight at her teacher and said, “…this is all a lie!” 28 pairs of eyes slowly moved from her to her teacher, who sat smirking at the front of the room. “You are absolutely right,” the teacher replied, “but can you prove it?”

Students should not only be expected to find information online but, perhaps even more importantly, they also need to be taught how to be critical of the information they find there, and how to corroborate, analyze and judge it’s validity. Most teachers would identify this as an important 21st-century skill, but how do you teach it?

At Hill-Murray School outside of St. Paul, Minnesota, we decided that this skill was important enough to include into the digital literacy lessons our students complete every year as a way of helping them develop the skills they need to survive and thrive in a technology-rich learning environment. I was lucky enough to lead a collaborative team of teachers and counselors that planned and delivered lessons focused on topics like cyber safety, cyber bullying and effective digital communication, along with a particularly engaging lesson that focuses on information literacy.

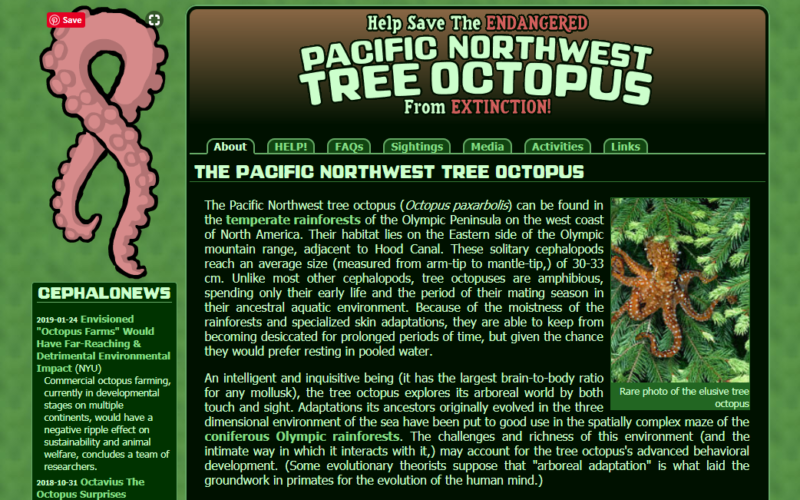

Early on in the year, students learn about evaluating information with a fun and engaging lesson as part of our school’s digital citizenship curriculum. The lesson begins with some “invisible theater” where the teacher tells her students that they are going to be learning about online advocacy and provides them the link to a website as an example. As students open the link in their browsers, the teacher explains how websites can be used to advocate for a cause they believe in, even one that isn’t well known. The website discusses the plight of the Pacific Tree Octopus, an endangered species that most people have never heard of because corporate lumber interests have suppressed knowledge of its existence so they can continue to log in its habitat. This made the students upset, connecting with them emotionally and pulling them into the lesson. On the surface, the website looks very legitimate with all sorts of sources, updated news feeds and lots of illustrations and professional-looking artwork. The teacher tells the students to spend some time evaluating how a website like this one can help create concern for the tree octopus and what kinds of methods it uses to try to get the public to take action.

While the website may pass a cursory examination, it doesn’t generally take long for one inquisitive or detail-oriented student to begin to see the multitude of problems with the site. Clicking on links results in 404 errors. There is a suspicious absence of scientific attributions on the site. And many of the pictures of the endangered tree octopus are actually stuffed animals or plastic toys stuck in trees. After a few minutes, students begin to share their findings with each other and their curiosity quickly turns into skepticism, which is exactly the process we want our students to engage in when they approach any unknown or suspect source of online information. On the day I was helping to facilitate the lesson, it was at this point that our previously-mentioned rabblerouser stood up and decried the authenticity of the site in front of the entire class.