Do Now U

Should global efforts to completely eradicate polio continue or is elimination of the disease enough? #DoNowUPolio

How to Do Now

To respond to the Do Now U, you can comment below or post your response on social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, Vine, Flickr, Google +, etc. Just be sure to include #DoNowUPolio and @KQEDedspace in your posts.

Learn More about Polio and Disease Eradication

An Egyptian tablet from around 1400 BCE depicts the first ancient polio victim, a man with his leg deformed by what appears to be wild poliovirus (WPV). Even though polio has been around for a long time, it became a real issue in the 20th century when epidemics broke out in Europe. Most polio victims show minor symptoms, if any at all. The worst effects of polio occur in about 1 percent of infections, when the disease enters the central nervous system, causing paralytic disease or paralysis. Polio is typically transmitted by contaminated food and water sources and, in the years preceding 1961 when Albert Sabin developed a cost-effective polio vaccine, half a million people died or became paralyzed because of polio per year.

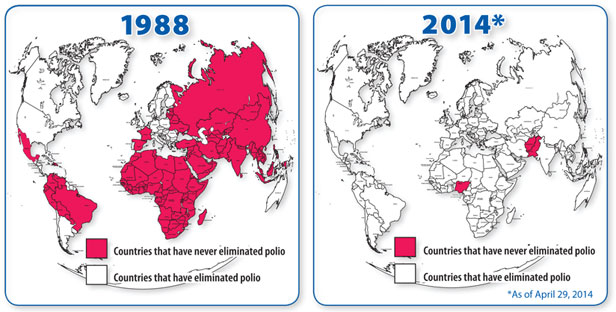

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), which includes immunization and education campaigns, has decreased polio cases about 99 percent since 1988. Despite great progress, in 2000 (the World Health Organization’s target year for complete elimination), polio cases were still reported within 23 nations. As we continue to push back an anticipated date for eradication, some ask why hasn’t polio been eradicated and whether or not eradication should be the goal at all. In the field of infectious diseases, scientists differentiate between control (reducing the incidence of a disease); elimination (stopping transmission of the disease in specific geographic areas); and eradication (reaching zero cases worldwide). So far, only one disease, smallpox, has been eradicated. We’ve become effective at the control and elimination of polio, but the eradication of the final 1 percent of WPV cases in the three remaining endemic countries (Pakistan, Nigeria, and Afghanistan) will be challenging.

Smallpox is the only disease to be completely eradicated, and since it is easy to identify, the entire 10-year process cost only $100 million. Because so many polio cases are invisible, the campaign to detect, contain and eliminate polio has lasted 27 years and has cost $4 billion. Complete eradication and necessary follow-up is predicted to cost an additional $1.2 billion and will depend heavily upon foreign aid. The two existing types of polio vaccines present a difficult trade-off: live oral polio vaccines (OPVs) are inexpensive and easy to distribute but pose a small risk of vaccine-derived infection. Inactivated polio vaccines (IPVs) are safer but expensive and require training to distribute. Complete polio eradication will be impossible unless the expensive transition to IPVs is made. Instability in conflict areas, and misinformation leading to people resisting or refusing the vaccine further complicate polio’s endgame.