Bias often shows up in knee-jerk reactions to discussions about changing the texts students read. And if teachers haven’t considered the factors that influence their thinking, or how their experiences and upbringing might inform what they do in the classroom, then adding new texts to the curriculum won’t be as transformative for students as it could be. After all, teachers set the tone; they’re the models and wield power over students’ lives.

Torres explained that a core part of this work is recognizing that every text has a particular perspective and was written at a particular time. That’s not necessarily good or bad, but teachers must recognize that context, and help students to interrogate what it could mean for the text. She points out that literature cannot be divorced from the social, political and cultural context in which it was made. So when teachers have nostalgia for certain texts, it comes with more weight than they may at first realize.

“Literature written by white authors tends to exclude or misrepresent the experiences of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color),” Torres said. “We want own-voices texts. And there are lots of authors who will back up that desire.”

She also urged teachers to think carefully about how much space they create in their classrooms for students to voice discomfort with specific texts or their opinions about alternatives. “We have to really consider how are we rewarding conformity and punishing resistance,” Torres said.

As teachers dig into self-exploration work at the foundation of the #DisruptTexts movement, Torres boils it down to five points:

- Figure out where you are. Be honest about where you are. Recognize people won’t all be in the same place.

- Look for tools that will help you expand your world with your students. Listen to students.

- Be honest with yourself about whether you’re creating ways for students to push back safely.

- Consider ways to empower students by involving them in the practice of decolonizing thinking.

- Recognize the ways we are all complicit in perpetuating systemic oppression and consequently responsible for dismantling it.

“This is not work that someone else needs to do,” Torres said. “This is work we all need to do.”

Pillar #2: Center black, Indigenous, and voices of color in literature

A quick search of the most commonly read high school texts turns up a lot of white male authors: Fitzgerald, Shakespeare, Golding, Hawthorne. No one is saying some of these texts aren’t worthy of study. The concern is that there isn’t balance.

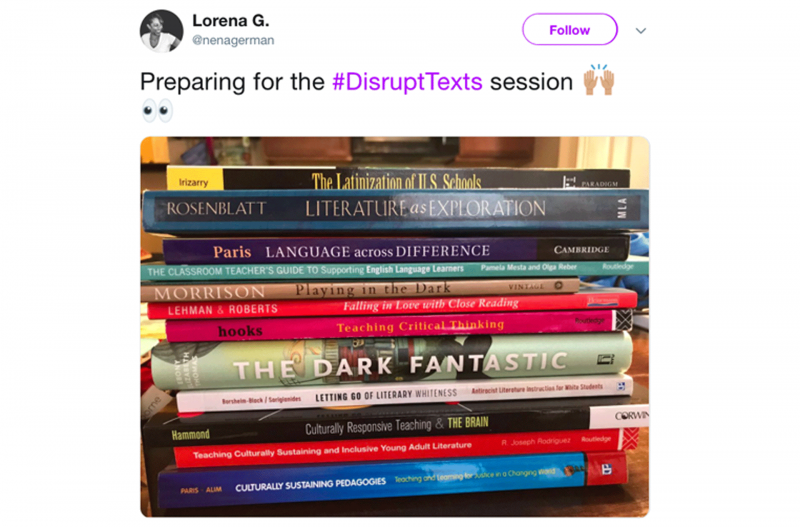

“So much of our literary canon is centered on the white gaze and written by white male authors,” said Lorena Germán.

“The issue is when the curriculum is all of that, and when the canon is mostly that.” Sometimes that white gaze has even been internalized by authors of color, which is why it’s important to remember the vast diversity of experience within communities of color. Just as one white man doesn’t speak for all white people, one black author does not speak to the experiences of all black people.

The dominance of white-authored texts in the curriculum is a problem for Germán and the other #DisruptTexts founders. They don’t see those stories connecting with their students, and worse, some of those stories actively exclude their students.

“It is for white people, by white people, and about white people,” Germán said. “That is the message that is received. That is the message I received in school.”

Germán urged teachers to find books that explore “the intersections and the margins,” to look for complex identities that resist stereotypes. She’d like to see teachers fill what Ebony Elizabeth Thomas calls the “racial imagination gap,” the implicit message, even in fantastical works, that people of color are the villains and monsters.

To center BIPOC voices and narratives Germán suggests:

- Strategic pairing. Put texts in conversation with one another. Ask: How does one text fill the gaps of another?

- Intentionally replace some texts. “There are some books that in and of themselves are problematic,” Germán said. “They feature characters that are straight-up racist or sexist. That is true. We can replace those texts.”

- Strategically create counternarratives. Push against tendencies to put people in boxes. Instead, think of ways to add complexity and change perceptions.

Pillar #3: Apply a critical literacy lens to our teaching practices

“It’s not just about having a checklist of diverse books,” said Tricia Ebarvia. She referenced Chad Everett’s work when she said, “There is no such thing as a diverse book. When you say diverse book, diverse for whom?”

Ebarvia explained that at its core, critical literacy is understanding that the world is a socially constructed text that can be read and analyzed like other texts. “There is no neutral,” Ebarvia said, which means school is not about acquiring knowledge, but rather thinking deeply about the meaning we ascribe to that knowledge.

Critical literacy is not a unit of study, but rather a way of reading the world. When teachers help students to read the world critically it can open up powerful conversations. It may even give students permission to share their lived experiences, or ways they do and don’t see themselves in school texts, in unexpected ways. And, it highlights the systems in which we work, live and read.

Ebarvia described some ways she teaches critical literacy with her high school students. She assigns the introductory essay in Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s book “Writing on the Wall” to students. In it he describes how most people look at him and see only a basketball player. They don’t know that he’s also an author, a historian and a social justice ambassador. Through this essay, Ebarvia introduces students to the idea of what’s “above the line and below the line.” In this example, basketball is “above the line,” it’s what people know about Abdul-Jabbar. The other aspects of his identity are “below the line.”

This simple formulation works for all kinds of analysis. Ebarvia asks students to think about their school. What’s the above the line information? And because they are insiders there, what’s below the line, that maybe Ebarvia, as a teacher, doesn’t know?

Ebarvia likes this exercise because it gets students thinking about the dominant narrative and the less explicit ones. It allows her to teach books like The Great Gatsby with integrity. If the dominant narrative in The Great Gatsby is about “the American Dream,” what is the non-dominant narrative? Whose dream? What characters are centered? Who is at the margin and why? What points of view can she bring in from outside the text?

Ebarvia tries to build text sets that are diverse and inclusive. She recommends asking for students’ help building those text sets. Think expansively about what constitutes “text.” Maybe a rap song speaks to the gaps of experience and perception in a white-authored text, for example.

Another exercise Ebarvia does with students is a writing reflection that asks students to reflect on who they are and how that identity and lived experience affects how they read the text. But she also pushes them to think beyond their own frame.

As a __________ (identity), I see __________ (issue) with/as __________ (opinion/perspective) because in my experience,__________ (support).

However, I recognize that that my view may be limited because__________.

In order to deepen my understanding of this issue, here are some of the questions I need to explore: __________.

Pillar #4: Work in community with others, especially BIPOC

“Community is built on accountability,” said Dr. Kim Parker. She urged educators to work at de-centering whiteness in schools and in the curriculum. She called on white educator allies to lift up the voices of BIPOC colleagues, especially those who don’t already get a lot of attention.

“We’re not trying to save anyone,” Parker said. “We’re trying to be in service with.”

That means honoring the knowledge and power in the community, the connectors and the ways of getting things done. Be humble. Listen.

She called on white educators who believe in this work to stand up for it to administrators, parents and other teachers. “For the white people in the room, your voices carry so much more weight than ours do, honestly,” Parker said.

And she referenced Elena Aguilar’s theory about “spheres of control.” What can you control? The internal work is something each person can control. What can you influence? Teachers influence students and colleagues all around them, and some push beyond that to Twitter, conferences and the broader education community. Everything else is outside your control.