"There were a few kids that really liked it," O'Malley said, "and I saw them go and get their friends and bring their friends back and say, 'You need to try this, this is so good.'"

But of course, like everything in school, even fun has a message.

"We are offering a festival for 'California Thursdays' to tie farm to school, into the lunchroom, so (students) learn the connection," said Michelle Drake, director of food and nutrition for Elk Grove Unified School District.

"This district is the fifth-largest district in the state of California, and we feed about 35,000 kids a day," Drake said.

Today in the cafeteria, all those kids are getting whole wheat penne pasta with chorizo and kale. All the food is from local farms, Drake says.

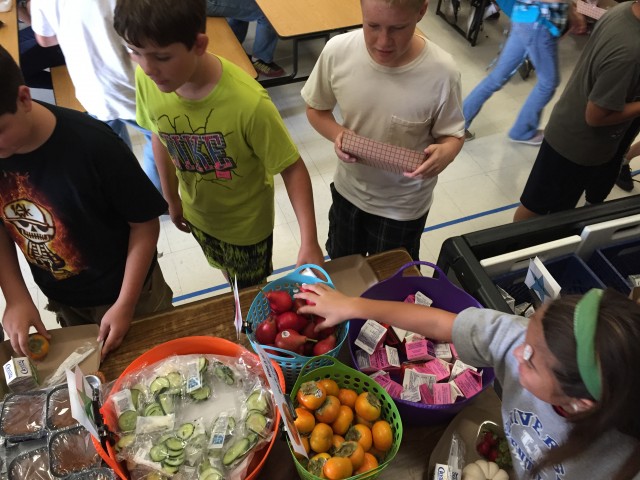

"I've got persimmons on the lunch line today," she said. "How many kids have ever had a local persimmon?"

In all, the "California Thursdays" program serves lunch for nearly 1 million schoolchildren in the state. That's about 1,700 schools in 15 districts.

Karen Brown is creative director of the Center for Ecoliteracy, a nonprofit based in Berkeley working with schools on sustainability. While the districts pay for the food, she says, Ecoliteracy keeps cost down by doing all the legwork including contacting farmers and setting up the kitchens.

Brown said their first test school district was in Oakland -- and what they found there was typical of many school cafeterias across the state.

"They weren't even doing freshly prepared food then," Brown said. "They were mostly just doing heat and serve."

So workers from Ecoliteracy had to set up the kitchens, pretty much from scratch.

"For me, one of the things I find the most remarkable," Brown said, "is that they didn't have measuring cups. They serve 7 million meals a year in Oakland Unified, and they didn't have any measuring cups."

Changing the habits of our cafeterias and the diets of our children is crucial, Brown said.

"One-third of the kids in America are overweight or obese," she said. "A lot of children get 35 percent of their calories every day at school. Some kids get more than half. So it's very important that those meals be as healthy as possible."

Back at the Elk Grove cafeteria, food director Michelle Drake is bracing for the next wave of kids, making sure there's enough tomatoes, strawberries, pomegranates and carrots on the fruit and vegetable cart.

"We thought it was cool we put color rainbow cauliflower -- so we have purple, green and yellow cauliflower," Drake said. "Kids love it just because it's colorful."

A fifth-grader named Audrey checked out the bright orange persimmons. She grabbed one from the pile and took a nibble, then a bite and seemed to decide it was okay.

"I liked it. It was really good," Audrey said. "It was sweet. It was kind of like a light peach, like a really light peach flavor. But it's really good."

Which, of course, brings joy to the ears of project organizers.

It's how health can start: One child, liking one persimmon. It's a microcosm of a shift in the taste buds and eating habits of a generation that doesn't know how to cook -- and snacks on Kit-Kats and corn chips.

One thing, though, said Audrey:

"It tastes better without the skin. It'd be easier if they had it without the skin when they give it to you," she said.

Ah, see? You get them to try other foods, bring those food ideas home to their families, that's great. But now you have a discerning eater on your hands.

Maybe that's the point.

David Gorn is senior reporter for California Healthline.