Although Cornell later readmitted him to the program, Latthivongskorn worried that medical schools would not want to admit a student who was living in the country illegally. He feared that schools might balk at a student who would have no guarantee of being able to practice medicine in the future.

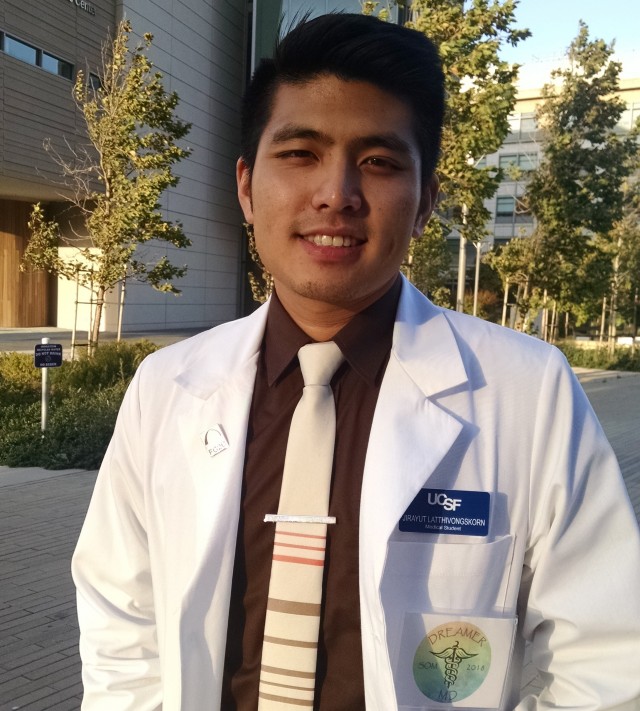

Speed forward two years to last Friday. UCSF formally admitted its new medical school class, and one of the 149 students is Latthivongskorn. UCSF says he is its first undocumented immigrant student. Along with the other students, he was ceremoniously awarded a physician's white coat.

The ceremony marks the official start of a student's medical training. I talked to New about his achievement and the obstacles that lie ahead.

(Below are excerpts from our conversation; questions and comments edited for clarity.)

Mina Kim: What does it mean to you to reach this milestone?

New Latthivongskorn: Definitely surreal, thinking about how much work it took to get here and how many people and family friends and community really supported me.

MK: Are you guaranteed to do your residency, at which point you’ll need to be employed by a hospital?

NL: With Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, DACA, I have a work permit so I would be able to. However, there is always uncertainty with immigration and policy, and what would happen to [DACA] two years, five years down the road.

MK: How are you financing medical school when you're not eligible for federal loans?

NL: I am very fortunate that the university is able to provide some form of grant funding, private funding that the university has, donations from alumni or various funding sources that the university has. And that’s only possible because of the California DREAM Act, which is a state law that provides for private funding to be accessible by a person like myself.

That helps with a chunk of my tuition. (But) housing and other fees, I essentially have to come up with on my own. I’ve been looking into private loans. I am applying vigorously for private scholarships.

MK: How do you respond to the issue of fairness? Is it fair to give a spot at a top medical school to an undocumented student, the child of a family that broke the law?

NL: Now, DACA means students are able to get a work permit, they're able to get residency, they're able to get licensed, so what are the real practical concerns of admitting an undocumented immigrant. Financial aid is a big issue.

The real purpose is being able to train someone who will be able to effect change and improve health for the communities around us. Myself and other folks who are undocumented understand these communities. We have grown up here, we have experienced being at the edge of no access to health care. I think that we bring a really important perspective that can be seen as a positive and as an added perspective, instead of immigration status being seen as a minus.

MK: Two years ago, after you were re-accepted as the first undocumented student to a Cornell internship, you told me:

"It's not just about myself anymore; it's bigger than myself. If I go and I do well and they really see this is what is possible from an undocumented student, it could potentially open up a lot more doors for a lot of other students who right now are in the same boat as me."

MK: Is that a pressure you continue to feel, and has it intensified by being the first undocumented medical student at UCSF?

NL: It definitely is still very much present, and in many ways the stakes have gone up now that I am in medical school. I’ll try to not only do well in school, but I’m always conscious of how it will be for the next undocumented student coming through the door.

Jirayut Latthivongskorn helped create a website that's a resource for other undocumented immigrants who want to pursue health careers.