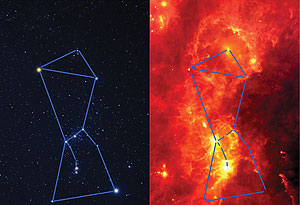

More than meets the eye: The constellation Orion

More than meets the eye: The constellation Orion

in visible light (left) and infrared (right)

Visible light image: Akira Fujii;

Infrared image: Infrared Astronomical SatelliteSome months ago my blog, "SOFIA: Fly By Night," talked about the up-and-coming astronomy ace of the night skies, SOFIA: the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy--a 2.5 meter infrared telescope built into a Boeing 747 airplane.

SOFIA's been flying, and is gearing up to begin its first science flights in the not so distant future. SOFIA even put in an appearance in Bay Area skies a couple of weeks ago with a quick visit to NASA/Ames Research Center in Mountain View--then it was off again to its base of operations in the Mojave Desert.

Having worked on SOFIA's predecessor, the Gerard P. Kuiper Airborne Observatory (KAO), in the last seven years of its operation, I thought I'd focus a bit on the science of airborne infrared astronomy, touching a bit on science done on the KAO over its 21-year career at NASA/Ames.

Why put a telescope on an airplane? Earth's atmosphere, while transparent to the visible light the human eye can detect, is less so to many other wavelengths of light, including most infrared light. In fact, the water vapor in our atmosphere is pretty much opaque to a wide range of infrared wavelengths.

KAO flew at and altitude of 41,000 feet to get above as much as 99% of Earth's atmospheric water vapor, giving astronomers a view of the infrared emissions from objects in space almost as if the telescope was out in space.