The European Space Agency's (ESA) Rosetta spacecraft is currently hibernating its way through space, en route to comet (get your pen ready) 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which is also currently in comet-hibernation far out in space. At this moment, in fact, the comet is almost as far from the Sun as it gets: about 5.6 Astronomical Units, or a little beyond the orbit of Jupiter. The comet and the spacecraft will rendezvous in 2014, then together swing closest to the Sun in mid-2015, at a distance somewhat within Mars' orbit (1.29 AU).

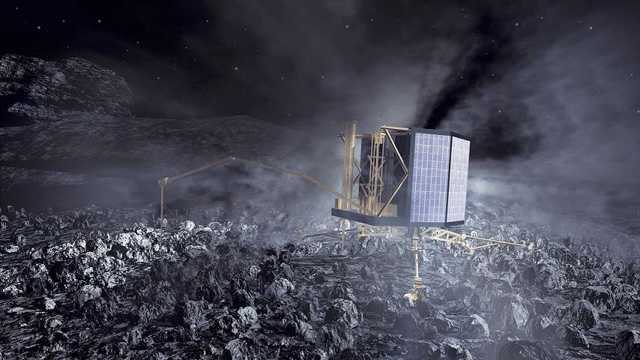

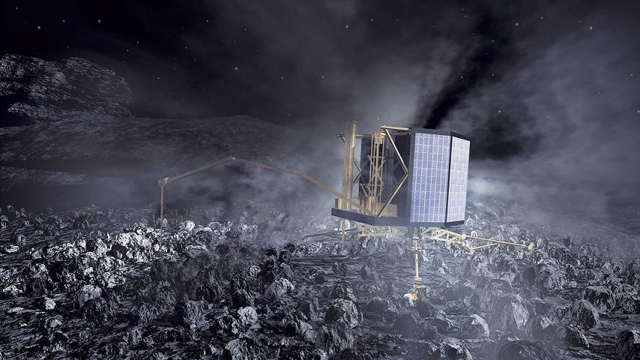

The TRUE mission of Rosetta, and its lander Philae, are not to save the comet from destruction, or to destroy it—but a kind of combination of the two: to observe and study it while the comet is in the process of falling apart, under duress from the Sun. The Rosetta orbiter and Philae lander will accompany the comet from a point in space still relatively distant from the Sun, and follow it along its eccentric orbit sunward. The comet and its stalking spacecraft will swing by the Sun, then outward into deep space again.

All the while, we will witness, for the first time, the process of a comet heating up under increasingly intense solar radiation, up close—not only up close from orbit, but with an observer "on the ground" as well.

We've watched comets do their Inner Solar System dance with the Sun since prehistoric times. The image of a comet that probably comes to your mind is what humans have watched in the skies, periodically, since long before telescopes: the fuzzy knot of the comet's coma—the shroud of gas surrounding the icy nucleus—and the long blurry, feather-like smear of its tail, blown off into space by the solar wind. This is the characteristic appearance of comets that human eyes are able to see, at least the ones that come close enough to the Sun to be warmed and exude a tail (or tails—usually one tail of gas, another of dust) and close enough to Earth to become a fixture in our night skies.

In recent years we've begun to witness comets up close with several fly-by spacecraft missions: comets Halley, Hartley 2, Wild 2, and some others. The Stardust mission actually captured dust particles from the tail of its comet quarry and returned the sample to Earth.

Rosetta will not only be our first up-close look at Comet 67P (etc.), it will be the first mission to follow the progress of a comet as it swings by the Sun, erupting in all its comet glory, then back out again toward another deep freeze cycle. It will also be the first landing on a comet ever. Should be pretty exciting.

I expect the time-compressed movie constructed from images taken by Rosetta and Philae to show a lot of explosions, sharp icy shrapnel bouncing off of armor…oh, and of course a treasure trove of less flashy but more substantial scientific knowledge of the life and times of a frozen time capsule that hasn't changed much since the formation of the Solar System five billion years ago….