Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: San Francisco and its surrounding Bay Area have long been known as a gay capital of the world.

Music starts

After all, it’s here, where the first lesbian civil rights group was formed, the Daughters of Bilitis.

And where Harvey Milk became an iconic gay public official! [tape]

Harvey Milk: I will fight to represent my constituents. I will fight to represent the city and county of San Francisco. I will fight to give those people who once walked away hope, so that those people will walk back in. Thank you very much. [clapping]

Olivia Allen-Price: It was the birthplace of the Gay pride flag. And it’s where city hall is lit up in a rainbow for pride month. This is the Bay Area that our question asker, Henry Lie, knows well.

Music stops

Henry Lie: I’m originally from Pacifica…went to high school at Terranova High School.

Olivia Allen-Price: Henry always thought of Pacifica as an extension of San Francisco — it’s just a few miles south, after all. And, there’s not a whole lot that surprises Henry about his hometown. That is until he learned about a moment in Pacifica’s history that left him with a ton of questions.

Henry Lie: We have this museum.. I think I was there and saw like a footnote or something and it just said like, oh yeah, Hazel’s Inn raid where, you know, there was a large gathering of LGBTQ+ identifying people and a bunch of people were arrested, couple of people charged.

Olivia Allen-Price: Henry had stumbled across a forgotten moment in history — a massive police raid that took place in 1956, part of a crusade to push LGBTQ people out of the Bay Area.

Ominous music starts

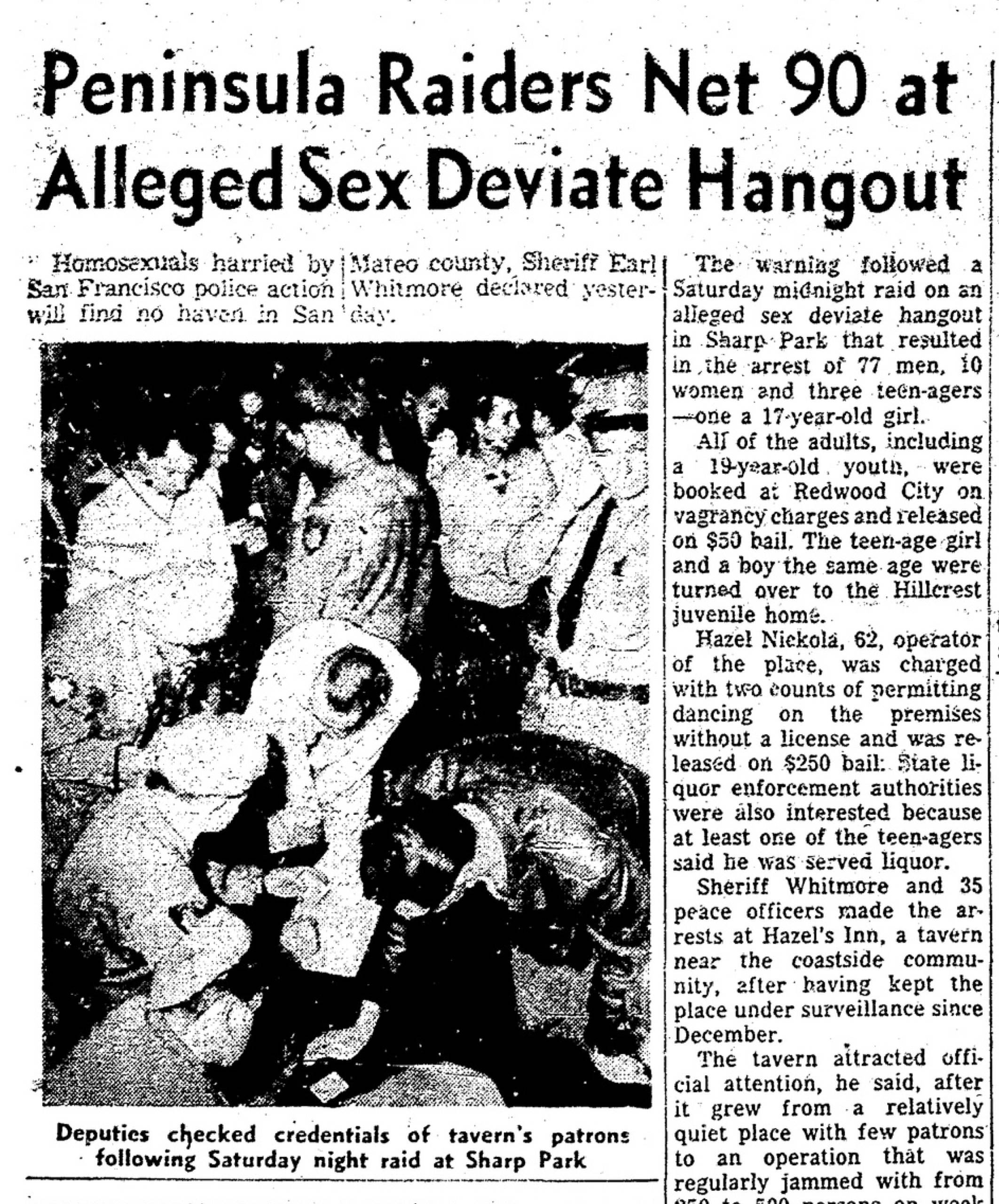

Local newspapers documented the raid.

Voice Over 1: San Francisco Examiner: Ninety persons, mostly men, were booked at the San Mateo County jail yesterday after a vice raid on a tavern suspected of being a gathering place for sex deviates.

Voice Over 2: San Mateo Times: The raid, according to Sheriff Whitmore, “was to let homosexuals know we’re not going to tolerate their congregation in this county.”

Voice Over 3: Redwood City Tribune: Mrs. Nicola, owner of Hazel’s Inn, is charged with operating a resort for sexual deviates.

Olivia Allen-Price: Big questions began surfacing for Henry.

Henry Lie: And I was like, whoa, I’ve never even heard of Hazel’s Inn. This says this was in Pacifica. Why have I never heard of it?

Olivia Allen-Price: So he came to Bay Curious, hoping to find out more.

Henry Lie: Could you dive deeper into the Hazel’s Inn raid in Pacifica and the effects that it had on the LGBTQ plus community in the greater Bay area in the late 1950s?

Bay Curious theme music starts

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen-Price and this is Bay Curious. This week, we’re going back to the gay bars of the 1950s to learn about a moment in time when the San Francisco Bay Area was far less welcoming.

All that coming right up.

Theme music ends

Sponsor Break

Olivia Allen-Price: To dig deeper into Bay Area queer history, KQED’s Ana De Almeida Amaral takes us to Pacifica.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Pacifica is a beautiful place, with sprawling views of the ocean and stunning beaches. It has that small town feel, complete with a tiny museum showcasing its history.

Laura Del Rosso: This is our little museum…

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Laura Del Rosso was born and raised in Pacifica, and serves as a docent and board member for the Pacifica Coastside Museum.

Laura Del Rosso: This whole area around here was full of speakeasies, taverns, restaurants, and brothels during Prohibition.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: It seems hard to imagine now, but this small town was once infamous for its nightlife.

Laura Del Rosso: Some people think that San Mateo County coast was actually the wettest place in the whole United States, meaning there was more booze here and in Half Moon Bay area than anywhere else in the country.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: While the historical society has long been aware of the clandestine nightlife during Prohibition, it wasn’t until a few years ago that they started uncovering the history of a hushed queer nightlife scene that took hold right here, in the 1950’s.

Jazzy music starts

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Hazel’s Inn was a tavern in Sharp Park, now a neighborhood in Pacifica. ^The bar is long gone^, but in 1956 the Pacifica Tribune, described it as a large and homey space, with knick-nacks above a mahogany bar, a shuffle board, a dance floor and a jukebox.

Hazel’s Inn was owned and run by Hazel Nikola, a straight woman in her 60s.

Laura Del Rosso: From what we understand then, after she got a divorce she was running the place by herself.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And the place was popular! Sometimes there were up to 500 patrons in a weekend. For a long time it catered mostly to locals and tourists on holiday at the beach, but then in 1955 and 56, the LGBT community made it their spot.

Laura Del Rosso: When the gay men started coming from San Francisco, she welcomed them. And she was non-judgmental. However, it’s obvious that somebody was not happy and did contact the sheriff.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: But before we can get to that night — the night of the Hazel’s Inn raid — we have to ask why here? Miles from San Francisco, hidden in a small town, far from any other gay nightlife, why was Hazel’s Inn the place that attracted hundreds of LGBTQ people?

Ana De Almeida Amaral: To answer this question, I went to the archives at the GLBT historical society — where collections documenting the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Trans community are housed.

There, I met Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd. She’s an oral historian with the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: I was professor of women and gender studies at San Francisco State for decades.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: She’s one of the few people who has researched queer nightlife in the 1950’s.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: 1956, 90 persons, mostly men were booked at the San Mateo county jail…

Ana De Almeida Amaral: At the archives we read some of the newspaper clippings about Hazel’s Inn.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: Suspected of being a gathering place for sex deviates…

Ana De Almeida Amaral: She did a lot of her research back in the 1990s and was able to interview dozens of queer people who lived in the Bay Area in the 1940s and 50s. Most of them have since passed away, so her work and these archives are some of the last links to this story.

Piano music starts

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Back in the 1940s, San Francisco already had a queer nightlife scene, but at the time it was illegal to be gay. And bars that were caught serving queer people… that was illegal too.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: If you were not a legal kind of person, then you couldn’t like buy a drink in a bar.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: But the law changed in 1951— when the Black Cat Cafe, in San Francisco, had its liquor license suspended for serving members of the LGBT community. The owner appealed the decision to the California Supreme court. The case is known as Stouman vs. Riley and it’s a big moment in queer civil rights history.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: The argument was that it’s not illegal to be a homosexual, it’s illegal to do homosexual acts.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: The court agreed. And the ruling became one of the first civil rights protections for LGBTQ people.

Music ends

Ana De Almeida Amaral: For the first time, they had the protected right to assemble. Gay men and lesbian women could buy drinks at bars and hang out with other queer friends.

That is as long as there were no homosexual acts taking place that were deemed “illegal or immoral.”

Like many legal decisions, it was a vague but powerful protection.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: I know it seems really regressive now, right? But the decision was liberating because the conclusion was that it wasn’t Status that was illegal, it was behavior.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And so queer nightlife in the Bay Area blossomed.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: In the early 1950s, I would say it was the heyday of gay nightlife in San Francisco.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And really iconic gay bars came into the picture. The Black Cat Cafe was running again, Tommy’s Place and Ann’s 440 opened. And these places became sanctuaries for the LGBT community to be together.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: There were maybe four or five quote unquote lesbian bars in North Beach in walking distance of each other at any point in time between like, let’s say, 1948 and 1955. So it’s like a really interesting community that evolved.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And this was really important because in the 1950s it was still not super safe to be gay. Many queer folks were closeted by day in order to keep their jobs. But at night…at the bar…there was a freedom that didn’t really exist anywhere else.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: And it was before the state caught wind of what was happening.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: But then a panic started to take hold in the United States…

Senator McCarthy archival tape: Are you a member of the communist conspiracy as of this moment?

Ana De Almeida Amaral: A conservative mindset took hold in American politics and culture — ushering in a time of suspicion and fear.

Senator McCarthy archival tape: Our nation may very well die, and I ask you caused it?

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And quickly, LGBT people become targets at the federal, state and local level.

President Eisenhower signed an executive order in 1953 banning gay people from federal work, labeling them as having immoral conduct and “sexual perversion.”

And, in 1955 California created a new state agency called the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control or the ABC. An agency whose sole job was to ensure that licensed bars abided by legal and moral codes.

And from the moment the department of Alcoholic Beverage control was created a top priority for them was to…

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: Shut down the gay bars.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And they did this by finding ways around those vague protections won in the Stouman v. Riley case.

While queer people were granted the right to assemble, “homosexual acts” were still illegal, so authorities started taking an interest in the specifics of what that meant.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: There’s a question about like, well then what exactly are the behaviors that are illegal? Like, do you have to like see someone, having sex in the bar? Or is it kissing? What about fondling? What about sitting on a lap? What about holding hands? What about dancing close? So all this stuff was like, then started being hashed out, you know, this is an illegal act.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control started collaborating with a bunch of law enforcement agencies throughout the Bay Area to ferret out people engaged in those acts.

By 1955, the gay bars in San Francisco were getting less and less safe.

And as harassment and policing increased, the LGBT community began looking for new places to gather outside of San Francisco, away from well-known gay bars, and they ended up down the coast, at Hazel’s Inn.

Sound design of a raucous bar scene

The only testimonies about what happened on Feb. 19, 1956, the night that Hazel’s Inn was raided, come from court documents and hearings at the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board. Laurence E. Strong, an ABC agent, described in detail what was happening at the bar.

That night, the dance floor was alive, and the bar was filled with around 200 patrons, mostly men. These men wrapped their arms around each other and embraced one another while dancing.

He also described how one patron sat on another man’s lap and how two other men held hands. In the corner of the bar, a couple embraced as one nestled his head into the other’s shoulder. Some men pinched each other’s butts and fondled each other while dancing. Women danced close together with other women. Men were seen powdering their faces and women wore slacks and sports coats.

It sounds like a scene of queer joy.

Music turns tense

Suddenly, 35 law enforcement agents stormed the bar — a mix of San Mateo county sheriff’s officers and ABC agents began arresting people. The sheriff jumped on to the bar and announced:

Voice over: “This is a raid!”

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Patrons were forced to walk past a line of agents. And one by one, agents picked out people they had seen showing queer affection.

Dr. Boyd says that the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board had been watching Hazel’s Inn for months, gathering evidence and building a case that behavior there was “illegal and immoral.”

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: They had undercover agents in the bars. And they would go in twos or threes and they would watch each other. And somebody would get an interested person, and then would sort of lead them on, until there was some kind of physical, sexual, or flirtatious engagement that involved touching. It was entrapment. And that was a common and acceptable practice.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Ninety people were arrested that night at Hazel’s Inn, including Hazel Nikola — the owner. The bar’s liquor license was quickly revoked for being quote “a resort for sexual perverts” and for serving someone underaged.

The mass arrest caught the attention of a variety of civil rights groups, including the ACLU who represented 30 defendants. Most of those arrested were cleared of charges, but the damage had already been done. People were outed in the newspapers.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: There would be a list of the people and their address and sometimes their occupation.

Voice over: The San Mateo Times: Local persons arrested were: Iris Ann Glasgow, 24 years old. Clerk. 1515 James Street, Redwood City.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Many of these people were publicly named as “sexual perverts”. That often meant being ostracized or losing their job.

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: People were so fearful.

Cello music starts

Ana De Almeida Amaral: As for the bar, Hazel fought the revocation of her liquor license for two years but the court ultimately sided with the ABC.

Laura Del Rosso: I think she was just really bitter about what happened here.

Music ends

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Back in the Pacifica Coastside museum, Laura reflected on what the raid did to Hazel Nikola.

Laura Del Rosso: She lost her liquor license and things just kind of went downhill for her. You have that information on the thing. And she ended up, she ended closing. She was very, very bitter at the end. She felt like she was really an important part of the community and that they had kind of betrayed her. She left Sharp Park and went to live somewhere else. And never came back.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: For the queer community, the effects were even more devastating. The Hazel’s Inn Raid became a playbook for the state to target the queer community over the next 15 years. (Surveillance, raids, and the revocation of liquor licenses.) It was a strategy to push LGBTQ people out of the Bay Area.

But it didn’t work.

Despite this aggressive policing and repression, the gay bars never died.

Queer patrons, and bartenders, and bar owners found ways to keep going. They found ways to spot surveillance in their bars, they organized and worked to keep the police out of their spaces.

Historian Dr. Boyd again:

Dr. Nan Alamilla Boyd: My takeaway from history as a historian is that during these times of repression. There’s cultural innovation that happens. You can’t really name it yet, right? But it’s taking shape you know, that there’s something coming.

Music starts

Ana De Almeida Amaral: During those years of extreme repression, queer activists were making connections, organizing, and laying the groundwork for the next several decades of activism that would see LGBTQ rights expand.

The Bay Area has changed a lot since the raid at Hazel’s Inn. But still, a fearless commitment to community and authenticity — the spirit that kept these gay bars alive — lives on here.

Olivia Allen-Price: That was reporter Ana De Almeida Amaral. Featuring the voices of Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman, Carly Severn, Christopher Beale and Paul Lancour for archival material.

Did you know that Bay Curious listeners help choose which questions we answer on the podcast? Each month we have a new voting round up at BayCurious.org, with three fascinating questions to choose from. This month…

Question 1: Did the Navy airship America crash land into several houses? What happened to the crew?

Question 2: Why is San Francisco home to so many federal and statewide courts? Why aren’t they in Sacramento or Los Angeles?

Question 3: I want to learn more about San Francisco upzoning and how people feel about it in the Richmond and Sunset districts.

Olivia Allen-Price: Cast your vote with one click at BayCurious.org.

Henry Lie: Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Olivia Allen-Price: Become a member today at kqed.org/donate. Our show is produced by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale and me Olivia Allen-Price. With extra support from Katie Sprenger, Matt Morales, Tim Olsen, Maha Sanad, Jen Chien, Ethan Toven-Lindsey and everyone on team KQED.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Have a wonderful week.