When Jacqui Young studied pre-calculus as a high school junior, she found the experience unexpectedly fulfilling. She didn’t consider herself a “math person,” but pre-calc came more easily to her than it did to most of her peers, and she spent a lot of time helping fellow students grasp the concepts. “It felt good to be able to understand something and then be able to walk someone else through it,” she said. “It was so gratifying, and made me want to stay on top of the subject.”

Satisfaction and engagement may not be the most common feelings among students studying introductory calculus. According to Jo Boaler, a professor of math education at Stanford, roughly 50 percent of the population feels anxious about math. That emotional discomfort often begins in elementary school, lingering over students’ later encounters with algebra and geometry, and tainting the subject with apprehension—or outright loathing.

Professor Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, associate professor of education, psychology, and neuroscience at the University of Southern California has explored how emotions are tied to learning. “Emotions are a piece of thinking,” she told me; “we think of anything because our emotions push us that way.” Even subjects widely considered to be outside the realm of emotion, like math, evoke powerful feelings among those studying it, which can then propel or thwart further learning.

Is there a way to separate negative emotions from the subject, so that more students experience math with a sense of satisfaction and pleasure? Immordino-Yang believes so. “It’s not about making math ‘fun’,” she added; games and prizes tend to be quick fixes. Instead, it’s about encouraging the sense of accomplishment that comes from deep understanding of difficult concepts. “It’s about making it satisfying, interesting, and fulfilling.”

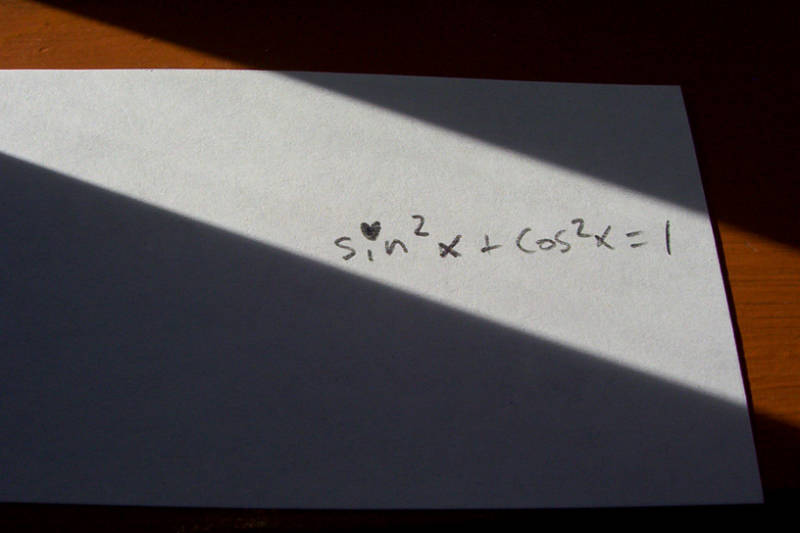

Adam Leaman, who teaches variations of algebra, trigonometry and calculus to high schoolers in Summit, N.J., said that a sense of awe about mathematics drew him to the subject beginning with algebra 2. “There’s something satisfying about knowing there’s an answer and knowing I have the ability to get it,” he said. Today, he sees the same pattern with his students: they are most engaged when they’re figuring out hard problems.