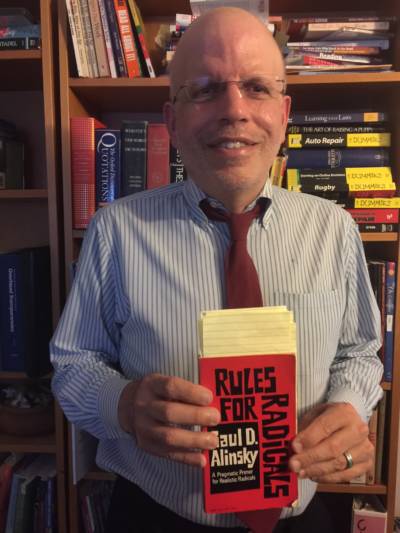

Educator, blogger and author Larry Ferlazzo teaches high school English and social studies, along with English language development, to a mostly English Language Learner population at Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento, California. He also writes columns for Education Week and The New York Times Learning Network. Ferlazzo said the book that has made the biggest impact on his life is Rules for Radicals, by sociologist and community organizer Saul Alinsky. Written in the early ‘70s as a successor to Reverie for Radicals, Alinsky's Rules for Radicals presents what Ferlazzo calls “a very pragmatic perspective on how to make change.” Ferlazzo said that reading the book changed the course of his life, and the book stepped in to articulate what he had been feeling about how to make change in communities.

Ferlazzo recently told MindShift how the book has impacted his life as both a community organizer and educator. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Ferlazzo: Rules for Radicals is a non-fiction book written by a man named Saul Alinsky, and it was written in the early 70s. He is sort of considered the father of modern-day community organizing. I was a community organizer for 19 years before becoming a teacher.

But prior to becoming an organizer, I spent seven years as part of the Catholic Worker Movement. The social justice perspective of the Worker is prophetic witness, that you’ve witnessed the world through civil disobedience and nonviolent protests. I think certainly there’s value in that, but I was feeling increasingly discontented with the idea of prophetic witness, it didn’t feel it was producing change in the world. And I heard about Alinsky and read his book and learned more about it, the perspective of: do you want to be right? Or do you want to be effective?

That’s the subject of the book: a very pragmatic perspective on how to make change. How I apply that to schools, and how I applied that to when I was organizing, was, you start where people are, not where you are. You build relationships, get to know what their self-interests are, and go from there.

For example, in the classroom, I’m teaching one day, we were doing a natural disasters unit in 9th grade, and students were supposed to write what they felt was the worst natural disaster to experience, and there was a student who refused to do it. He’d never done much writing. And I had really gone through developing relationships -- part of what Alinsky pushed was that you get to know people and get to know their self-interests, so I knew that he was really interested in sports. I said, “Well, why don’t you write an essay about who you think the best football team is?” He said, “I could do that?” I said, “Yeah!” You know, keeping my eye on the prize, the focus was helping students develop the ability to write a persuasive essay, not to really write about what the worst natural disaster is. He got very enthusiastic about that, and after he completed that he said, “Hey, Mr. Ferlazzo, can I write one about my favorite basketball team?” So I said, sure. A week or two later, there was an all-teacher meeting with this child’s parent, and she had tears in her eyes holding one of his essays, and she said it was the first essay that he had ever written in any school.

Even though I’ve never taught the whole book, I have used quotes of it in IB [International Baccalaureate] Theory of Knowledge class. One thing Alinsky really pushes is to always have an element of doubt in your beliefs. Be wary of anyone who doesn’t. In Theory of Knowledge, that’s a really important part, is always to recognize the difference between knowledge and beliefs.

Even though I’ve never taught the whole book, I have used quotes of it in IB [International Baccalaureate] Theory of Knowledge class. One thing Alinsky really pushes is to always have an element of doubt in your beliefs. Be wary of anyone who doesn’t. In Theory of Knowledge, that’s a really important part, is always to recognize the difference between knowledge and beliefs.