A body of research has shown that telling children that they’re smart and implying that their success depends on it fosters fixed mindsets. When these children later experience struggle, they tend to conclude that their ability is not high after all, and as a result they lose confidence, so our praise has the opposite effect of what we intended. On the other hand, praising hard work or strategies used, things that children control, has been shown to support a growth mindset.

This research was designed to learn more about one of the ways to support a growth mindset, not to identify all there is to fostering a growth mindset. When people newer to the growth mindset framework initially learn about this research, they sometimes conclude that we should simply praise children for working hard. But this is a nascent level of understanding. First, exhorting students to work hard would be an attempt to directly change behaviors without changing the underlying belief about the nature of abilities.

Second, students often haven’t learned that working hard involves thinking hard, which involves reflecting on and changing our strategies so we become more and more effective learners over time, and we need to guide them to come to understand this. For example, a novice teacher who sees a student trying very hard but not making any progress may think “well, at least she’s working hard, so I’ll praise her effort,” but if the student continues to do what she’s doing, or even more of it, it’s unlikely to lead to success. Instead, the teacher can coach the student to try different approaches to working, studying, and learning, so that she is thinking more deeply (i.e. mentally working harder) to become a better learner, and of course the teacher should do the same: reflect on how to adjust instruction. “It’s not just about effort. You also need to learn skills that let you use your brain in a smarter way. . . to get better at something.” (Yeager & Dweck, 2012.)

Third, cultivating growth mindsets involves a gradual process of releasing responsibility to students for them to become more self-sufficient learners, and praise is a communications technique that tends to be more helpful earlier in that process of building agency. Later on, adults can ask students questions that prompt them to reflect, so that they’re progressing down the path toward independence.

Fourth, praise and coaching are not the only, or most powerful, ways to foster growth mindsets. For example, another method is modeling lifelong learning and making it visible, which gets us to the next confusion.

Confusion #3: Growth mindset is about changing young people, not adults

Some recent criticisms paint growth mindset work as solely focused on the students and not the adults. This is a misunderstanding of what growth mindset efforts are about. In our work with educators, we encourage the adults to start with themselves. If we don’t work to shift our own mindset about ourselves and our students, then we won’t work to change many other important things in the system necessary to improve education. Furthermore, our efforts to foster growth mindsets in students are likely to fail because we will say and do things that reflect our fixed mindset beliefs, which students will notice. We must deeply explore mindsets within ourselves and then gradually work to develop our own growth mindsets and our habits as learners. This means authentically working to become better at what we do throughout our lives, including how we teach and how we create contexts that help students thrive, and making our learning process visible to one another and to students.

We encourage the schools we serve to train teachers early in their growth mindset efforts, involving reflections and discussions on adult beliefs and continuous improvement practices. We provide professional learning resources to help them do so. Dr. Dweck and other mindset researchers speak about the importance of fostering a growth mindset in adults and have researched the mindsets of educators, managers, leaders, and other grownups. Growth mindset research is about learning how we humans can all become more motivated and effective learners, not about how we can change students but not ourselves.

Confusion #4: All that matters is what’s in the mind

Another confusion about mindset is that the only determinant of success is our mindset. But that’s not the case. Context, culture, environment, and systems matter. For one thing, people's mindsets (as well as other beliefs and behaviors) are strongly shaped by the people around them. Beyond that, people's destiny is not only a function of what's within them, but also of what's around them. A lot of the early mindset research studies focused on individual's minds because they were seeking to understand how humans work. But mindset researchers recognize, research, and speak about the importance of shifting culture, context, and systems, and both researchers and practitioners actively work on that aspect of change efforts.

Confusion #5: Improvement is all about changing beliefs and not doing anything else

Related to that, another confusion we see, also reflected in recent commentaries, is that growth mindset work is solely about fostering the belief that we can improve, but not about changing the educational system or actually doing anything about that belief. Carol Dweck has talked extensively about changing learning tasks, testing practices, and grading systems. Too many tasks and teaching approaches are superficial, irrelevant, unengaging, and not learner-centered. We do need to change these tasks, the curriculum, and the pedagogy. We need to change the idea that school is about testing rather than about learning. We also need to better tackle broader issues such as childhood trauma and lack of exposure to early reading. People who dive deeper into growth mindsets learn about how important these issues are and how we might begin to address them, and a growth mindset helps them take on the challenges. As David Yeager and Gregory Walton point out:

[Mindset] interventions complement—and do not replace—traditional educational reforms. They do not teach students academic content or skills, restructure schools, or improve teacher training. Instead, they allow students to take better advantage of learning opportunities that are present in schools and tap into existing recursive processes to generate long-lasting effects . . . Indeed, [Mindset] interventions may make the effects of high-quality educational reforms such as improved instruction or curricula more apparent (Yeager & Walton, 2011).

Deepening our understanding over time

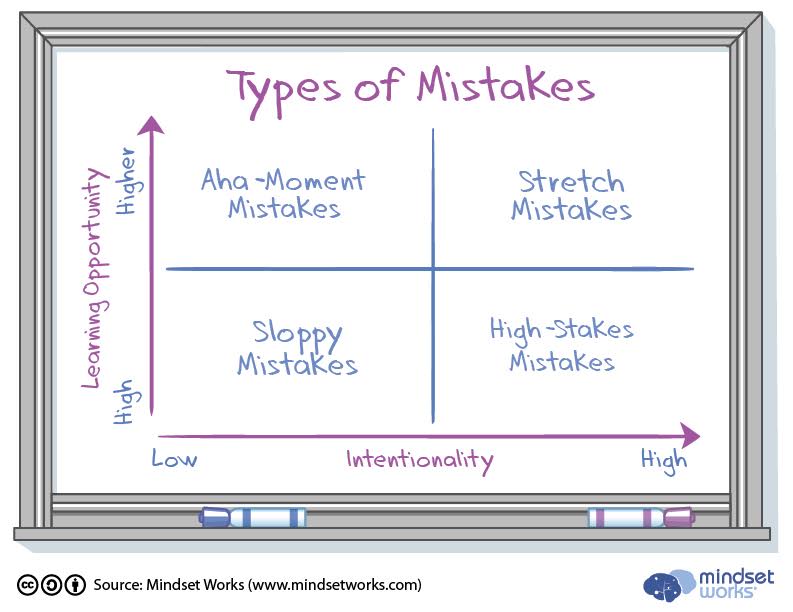

As with anything else, the deeper we go into mindsets, the deeper our understanding becomes. Over time, more nuanced questions arise, such as about the relationship between mindset and performance, results, failure, potential, assessments, mistakes, and many other things. For example, early on a teacher who is learning about mindset may start oversimplifying mistakes as always being ‘good’, but this can confuse learners, as mistakes are not always something we should seek to do. With time we start distinguishing stretch mistakes, sloppy mistakes, aha-moment mistakes, and high-stakes mistakes.

Growth Mindset Enables Change

Research has shown that developing a growth mindset is beneficial in a variety of contexts, from education to the workplace to interpersonal relationships to sports to health. It leads people to take on challenges they can learn from, to find more effective ways to improve, to persevere in the face of setbacks, and to make greater progress, all of which we need to further cultivate in education. Furthermore, there is evidence that its benefits are most pronounced for people who face negative stereotypes, such as underserved minorities and females in STEM, and as a result growth mindset efforts can narrow the achievement gap.

Let’s Learn Together

Growth mindset is a seemingly simple concept, but there is a lot of nuance to the framework and its applications. I hope that this article helps clarify common misconceptions. We invite people to continue diving deeper into this body of work and engage in explorations together. We welcome further feedback because it takes a village, or more precisely, all of us, to foster better learning.