It has been a bitter pill for me to swallow as a parent and as a bibliophile: my son does not love to read. Sure, I read to him daily when he was a toddler, and even once he learned to read to himself, we still spent many evenings reading books aloud as a family. (Thank you, J.K. Rowling for that.) But he's never been one to pick up a book on his own accord, even though bookshelves line almost every room of our house and even though I've got endless suggestions for books that I just know he'll love.

It has been a bitter pill for me to swallow as a parent and as a bibliophile: my son does not love to read. Sure, I read to him daily when he was a toddler, and even once he learned to read to himself, we still spent many evenings reading books aloud as a family. (Thank you, J.K. Rowling for that.) But he's never been one to pick up a book on his own accord, even though bookshelves line almost every room of our house and even though I've got endless suggestions for books that I just know he'll love.

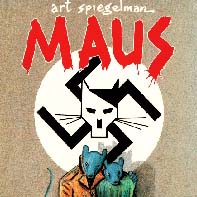

My son did not love to read, that is, until he was assigned Art Spiegelman's Maus: A Survivor's Tale. For those unfamiliar with the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, it's a graphic novel relating the biography of Spiegelman's father, a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. In the novel, the Jews are depicted as mice, and the Germans as cats. It's one of the most powerful pieces of literature about the Holocaust, I'd argue, and while its format as a graphic novel makes it very accessible, that isn't to say that the content is "watered down."

Though graphic novels can be an entry point for struggling or disinterested readers into the world of books, graphic novels and comic books have long been deemed the enemy of literacy. That was the attitude expressed earlier this month by sixth-grade language arts teacher Bill Ferriter, who wrote a great series on graphic novels on his blog The Tempered Radical. Commenters, I think, helped change Ferriter's mind somewhat, challenging him on his original argument that graphic novels were the literary equivalent of the reality TV show Jersey Shore.

But while schools move to embrace graphic novels and comic books in the classroom, the publishing industry's move to digital formats raises another set of challenges and possibilities for the genre. How will the move to electronic versions of comics and graphic novels change the way in which they are accessed, read, and -- most importantly, arguably with this genre -- shared?

That sharing piece has always been an important part of the comic book subculture, where often you hear about new series and new artists and new storytellers because a friend shares it with you. But as e-books typically come with rights restrictions, it isn't possible to lend someone your beloved digital copy of, say, Neil Gaiman's The Sandman. Some comic book publishers are recognizing the importance of sharing as an integral part of the comic culture and as such are making some -- the first issue, for example available without digital rights management (DRM), specifically so others can share them.