Trouble viewing the video? Stream or download it on PBS LearningMedia.

Article by Lauren Farrar

“What if you could drop microscopes literally around the world from an airplane?” Manu Prakash, a professor of bioengineering at Stanford University would often joke with his team.

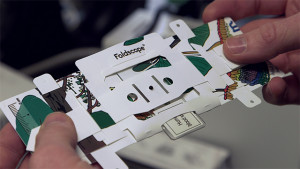

This musing actually heavily influenced the design of their new microscope, a paper origami microscope. They call it a Foldscope. The microscope is printed on waterproof paper. The user punches out the pieces and folds them together to create a fully functional microscope. It works with standard microscope slides and requires no batteries or electricity to operate. You simply hold the Foldscope up to a light source (like the sun) and look through the salt grain-sized lens to view the sample on the slide. The high curvature of the tiny lenses used in the Foldscope allows small objects to be highly magnified. This little invention costs less than a dollar to produce and could have major implications for global health and for science education.

Prakash grew up in small towns in India where access to healthcare and diagnostic tools, like microscopes, weren’t always easy to come by. He has traveled extensively throughout developing countries and has seen firsthand how diseases like malaria, African sleeping sickness and schistosomiasis can go untreated or are mistreated because patients are not properly diagnosed. Diagnosis of diseases like these usually require a microscope to identify the presence of a particular parasite so that the proper treatment can be administered. But remote or resource poor areas don’t always have access to these heavy, expensive microscopes used in other parts of the world. Standard microscopes are also difficult to transport when doctors travel from village to village to diagnose and treat patients. And even when remote places do have microscopes, there is little support to maintain them or parts available to fix them if they break.