If you’ve spent any time in the company of canines, you’ve probably observed their uncanny ability to sniff out the teeniest morsel of food on the kitchen floor, or locate the lone crumb lurking in the sliver of space beneath a couch. In many homes, dogs render an indispensable service every evening by searching out and “vacuuming” the fallen bits of dinner. Of course, dogs’ noses are being put to use for much greater good, such as detecting bombs, finding missing persons, and sniffing out drugs or other illicit objects. And now biologists have found yet another use for those cold, wet, miraculous noses: preserving biodiversity.

Around the world canines are being enlisted to track rare wildlife, sleuth out invasive species, and detect otherwise imperceptible changes that could harm wilderness areas and watersheds. But are these canines really providing significant support to conservation efforts, or is it just another excuse to bring your dog to work?

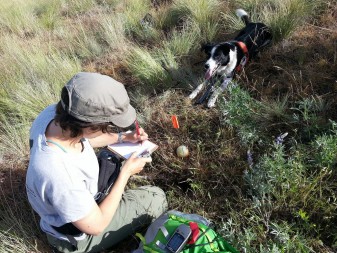

According to biologist Pete Coppolillo, putting dogs to work for conservation is not only effective but also an increasingly established methodology used by scientists and wilderness management authorities. As the executive director of a Montana-based nonprofit called Working Dogs for Conservation (WDC), Coppolillo and his colleagues have trained and dispatched dogs across 18 states and 11 countries. These wonder dogs have helped eradicate invasive weeds threatening to edge out native plants in Montana’s grasslands, identify beetle-infested trees in Minnesota forests, and detect and remove illegal wire snares set by poachers in Zambia. In the name of preserving biodiversity, these bold canines have sallied forth in ATVs, helicopters, and even on the backs of elephants to traverse the muddy roads of Myanmar during monsoon season.

But one of the most useful roles that dogs play in support of conservation is sniffing out scat (AKA animal poop). “Thanks to advances in technology and reduction of lab costs, analyses of scat can reveal not just what the animals are eating…but if they have elevated levels of hormones, and even genetic information,” said Coppolillo. Yielding important clues about life cycles, health, family groupings, and habitat range, these scatological portraits help us to better understand and protect wildlife. Scat analysis can also point to larger environmental problems, added Coppolillo, such as the presence of heavy metals, pharmaceuticals, and other toxins that can pervade both land and aquatic ecosystems.

Historically, the main methods for studying wildlife have required scientists to capture animals and outfit them with GPS collars for tracking or extract blood and tissue samples, invasive techniques that can pose threats to animals and researchers alike. Biologists and wildlife authorities have also gone to great expense to search for animals using small aircraft, with hope of determining things like population density and territorial range.