One of the last things the 112th Congress did in 2012 was to enact legislation that turns Pinnacles National Monument into the nation's 59th national park. It will replace Yosemite as the nearest national park to the Bay Area, so we should familiarize ourselves with its wealth of natural attractions -- including the geological.

Pinnacles has a lot to offer besides rocks and tectonics. It's a crucial northern outpost of the California condor and a stronghold of good habitat for all kinds of animals and plants. The park is reported, among other things, to be the most species-rich area in the world for wild bees. The park's plant checklist is 20 pages long, covering five major habitats. The views from its namesake peaks are phenomenal, and its night skies are dark as can be.

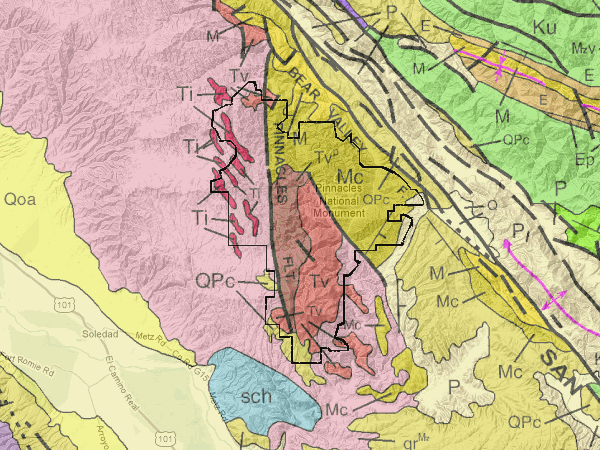

The pinnacles of Pinnacles are spires of volcanic rocks: rhyolite, dacite, andesite. These are remnants of a small volcanic complex that dates from early Miocene time, about 23 million years ago. That is quite a bit older than the volcanic centers of the Bay Area proper, which date from the late Miocene, but its tectonic origin is the same: the rearrangement of the Pacific and North America plates that created the San Andreas fault system.

The original volcano was probably not right on the new fault but east of it, and it was located near Lancaster in Southern California. We know this because soon after the volcano finished its business, the fault system took hold of it and wrenched it apart. Pinnacles is the western portion. The eastern portion is still down there, where geologists know it as the Neenach Volcanics. That's where I picked up this specimen of rhyolite, just like what you'll see at Pinnacles.

The Pinnacles/Neenach connection, or piercing point, documents about 315 kilometers of movement across the San Andreas fault. It's one of the fault's best-known piercing points.