The first sniffles of flu season are upon us: a friend of mine was struck down, and couldn't join me in attending a science dialogue on Sunday night. This was darkly humorous, as the topic of the evening was pandemics.

Provocatively titled "Is Nature or Man the Most Effective Bioterrorist?", the free event was co-hosted by Wonderfest (The Bay Area Beacon of Science) and Ask A Scientist (a lecture series for curious humans). The speakers hailed from Stanford: two-time Nobel nominee Stanley Falkow, professor of microbiology and immunology, and David Relman, professor of medicine and chair of the Forum on Microbial Threats (really!).

Falkow opened by summarizing the natural history of human-microbe interactions, from chronic "heritage diseases" like herpes--with us since hunter-gatherer days--to acute "crowd diseases" like measles that cropped up (see what I did there?) when people began to settle in larger populations to farm.

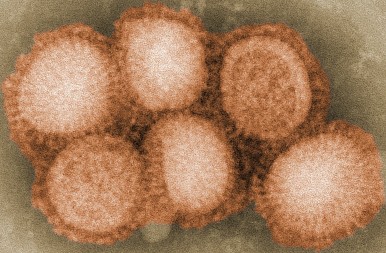

Human history has seen some pretty scary pandemics, from the Black Death in Europe to smallpox in the New World. But we survived long enough to invent vaccines and antibiotics, and mortality due to infectious disease has plummeted. The 2009 flu pandemic was a ghost of 1918. Does nature even have a chance anymore of winning "most effective bioterrorist"?

It might. We live in an ever more crowded, ever more connected world, and pathogens adapt to human behavior--right down to evolving antibiotic resistance. In 2007, says Falkow, "I thought nature had done a hell of a good job, and it was going to be hard to beat."