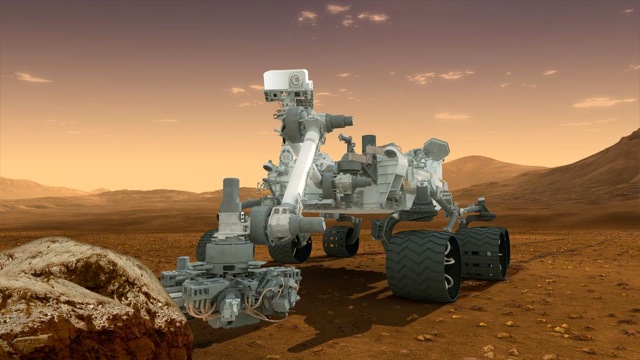

On August 5, the world was abuzz about a rover named Curiosity landing on Mars. Now that feat of masterful engineering is over, the rover wakes up, starts its instruments and begins its business of chemistry.

More specifically, Curiosity is looking for elements and molecules that could be clues to past life on the planet. Elemental analysis is one of the most basic things chemists do, as it helps them figure out products formed in a reaction.

In graduate school, I worked in a lab that built complicated molecules that could be potential medicines. I mixed powders and liquids in a flask, waited for a reaction and then set about identifying what I made.

Most of the time I started a reaction knowing what the products should be. Sometimes I retrieved those products. Other times the reaction took an unexpected turn and I collected products with too few or too many atoms. That's when the chemical detective work began. Knowing what products the reaction created, I used my knowledge of chemistry, the reaction conditions, and the materials in the flask to guess how those side products might have formed.

Curiosity, the wandering robotic chemist, might find molecular products like methane or protein building blocks possibly formed by past life on Mars and now trapped in rocks and minerals. But scientists analyzing the significance of those clues have an extra challenge that I didn’t: They don’t know reaction conditions on the planet, like time, temperature and acidity, which could affect how those products formed.