Did you know there’s chemistry in art conservation? Conservators want to know the chemical composition of paints and sculptures so that they can restore damaged areas or prevent delicate materials from degrading. Sometimes they're measuring the elements in pigments with X-rays. Other times scientists try to figure out how a pigment changes as it ages so that they know how to handle the altered areas.

The best instruments get that information without damaging the artwork, often with light beams. Near-infrared light can help scientists identify the chemical composition of degradable plastics and iron ink. It also penetrates a painting’s surface, helping restorers find any lines or cracks below the top layer of paint.

A new technique developed by Italian researchers offers a clearer picture of pictures hidden underneath frescoes. The scientists shine a low power halogen lamp on the fresco and detect the reflected mid-wave infrared (IR) light with a wavelength about 3 micrometers long. That’s about 4 times longer than the wavelength of red light, which is the longest waves our eyes see.

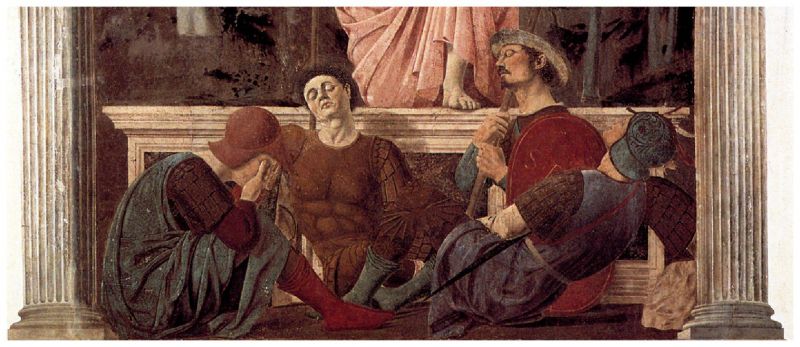

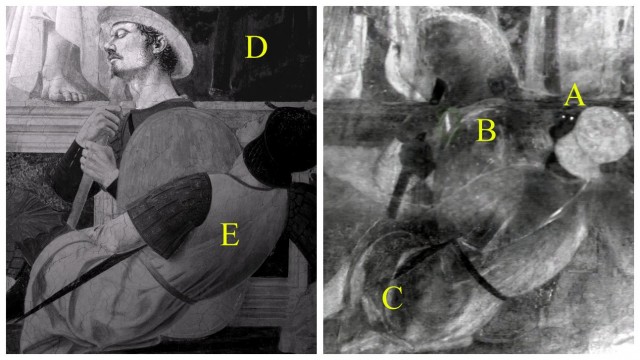

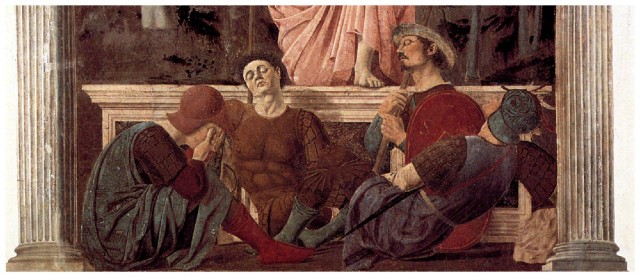

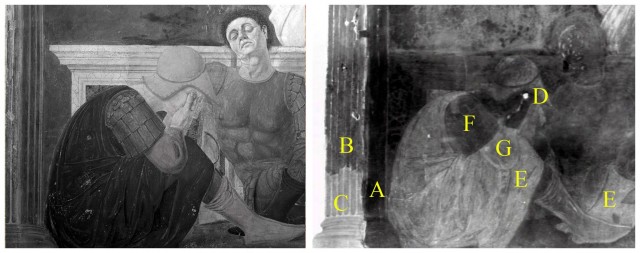

To test their new method, the researchers set up their lamps near a mural in an Italian art museum while visitors were mulling about. They took pictures of “The Resurrection” by Piero della Francesca (above) when it was bathed in visible, near-IR (wavelength 0.75-2.5 micrometers) and mid-range IR light.

Under visible and near-IR light, the shoulder and sleeve of one soldier appear the same color. But the two areas reflect light differently when using the new imaging method (see F and G in the picture above). That means they were painted with different pigments.