For 18 days before the ransomware attack actually commenced, the implanted malware sat dormant in KQED’s computer system. It was probably sniffing out usernames and associated passwords—plus the systems each unlocked. Eventually, the malware got hold of an account with the ability to enter anywhere and do anything, called a domain admin account.

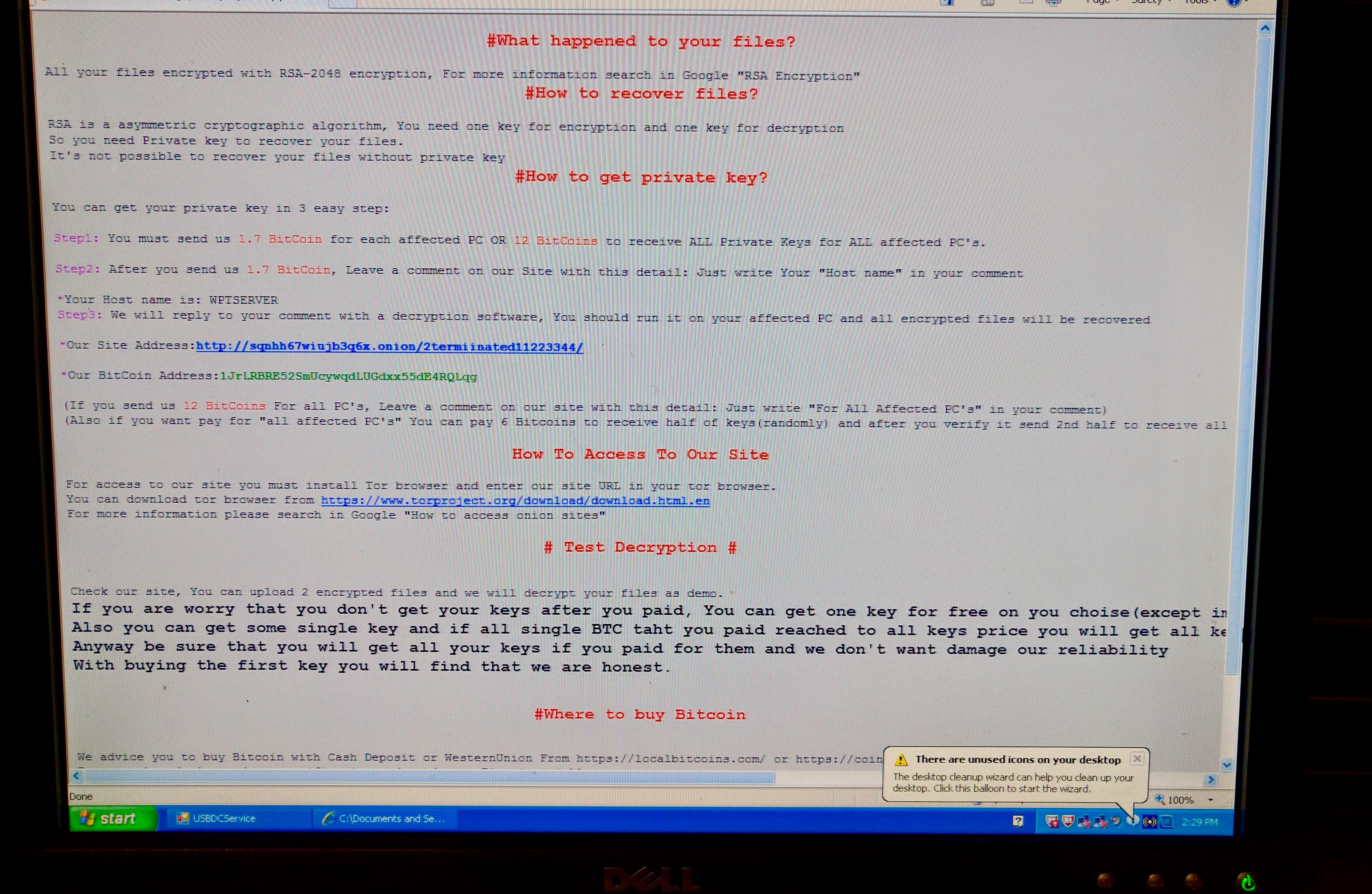

That allowed the malware to propagate throughout the network, infecting machines, locking up files and informing staff members via desktop messages that they were now official ransomware victims.

You can limit the widespread nature of a malware infection by managing a sort of security trap related to a Microsoft networking tool called Active Directory. It stores accounts, the systems that each account is allowed access to and the level of access each account is afforded.

KQED's problem was that many of our systems were grouped together in Active Directory, under what’s called a domain. The reason for this is convenience: When different systems are part of a single domain, people can use the same user ID and password for each. So someone logging onto their computer in the morning could then do work on the audio content management system and financial software, or the audio and video editing software systems, all with the same user ID and password—no need to remember a different set for each.

The downside of this setup is if intruders get hold of a single high-level account, they can go from system to system, infecting each.