Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: We start today’s episode in Garin Regional Park – high in the hills overlooking Hayward. If you drive over this way, you might pass by an intriguing sign. That’s what happened to Tony Divito of San Mateo.

Tony Divito: I saw a sign for a Ukrainian farm in Hayward. I just wanted to know the backstory.

Olivia Allen-Price: Deep in the park is California registered historical landmark #1025.

VOICE: “Ukraina” is the site of the farm and burial place of the Ukrainian patriot and exiled orthodox priest Agapius Honcharenko (1832-1916) and his wife Albina.

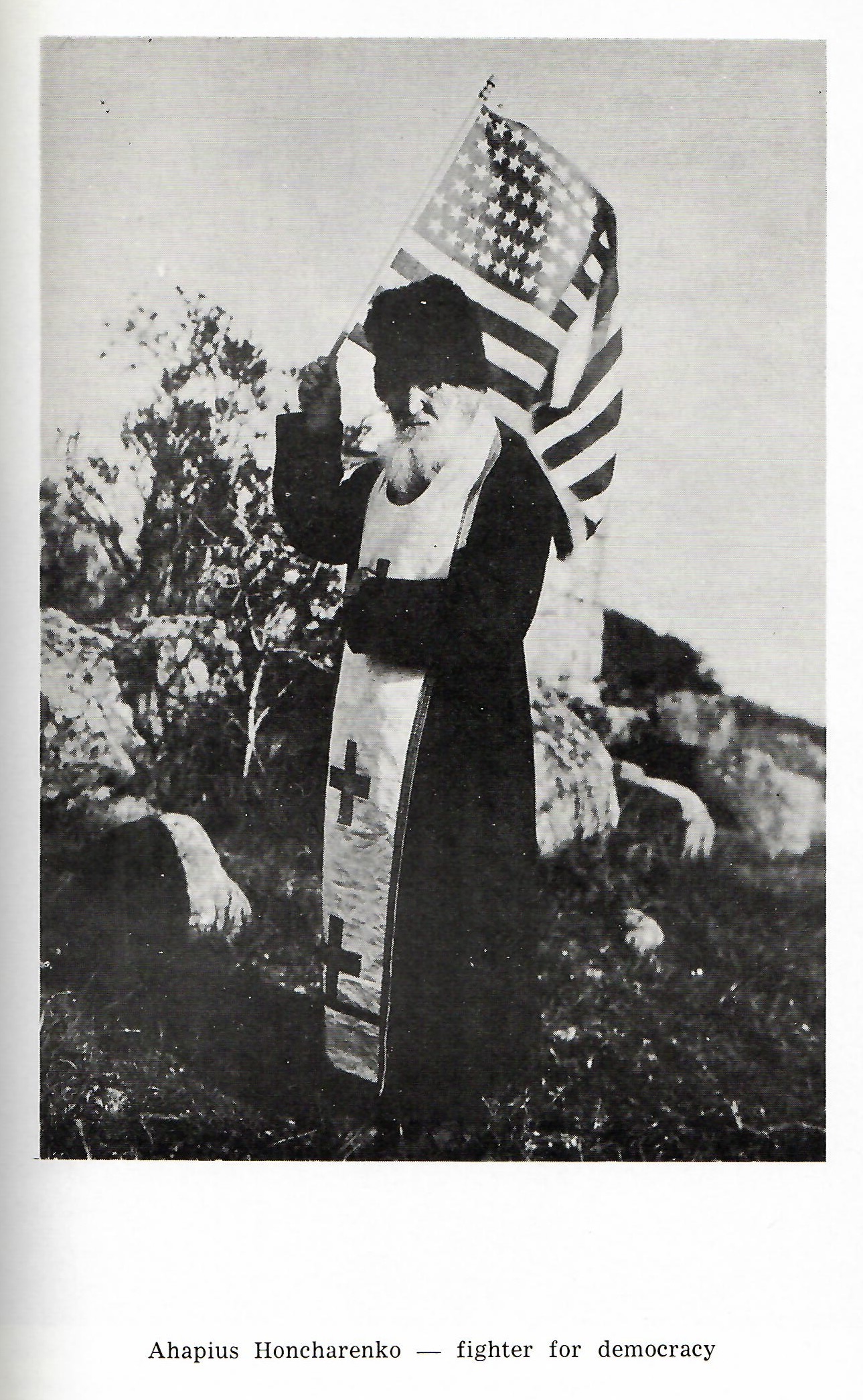

Olivia Allen-Price: It’s a serene setting now, but the life of this guy – Agapius Honcharenko – was anything but. He spent much of his life fleeing Russian forces, traveling the globe and stirring up revolutionary inklings in his wake. Not exactly the image you might expect from an orthodox priest. Today on the show, we’ll delve into what made Honcharenko so notable that more than 100 years after his death, he’s still celebrated by local communities. Buckle up, it’s a wild ride! I’m Olivia Allen-Price. You’re listening to Bay Curious.

Sponsor Message

Olivia Allen-Price: In the 19th century, all sorts of curious characters washed up on California’s shores, looking for fortune, a fresh start, or in the case of Father Agapius Honcharenko … a safe place to hide. KQED’s Rachael Myrow found a group of people who gather every year to honor him. She went to find out why…

Singing in Ukrainian

Rachael Myrow: The mood was contemplative, even somber, at the 9th annual Park Ukraina Hike and Panahdya — a memorial service for Honcharenko. Representatives from local Ukrainian churches hiked a mile to offer prayers over the grave of a remarkable man who established a farm here on this hilltop.

Man reading a prayer in Ukrainian

Rachael Myrow: Software engineer, Alla Kashaba was among the 20 or so in attendance. She lives in Los Altos now, but comes originally from Karghiv, in eastern Ukraine.

Alla Kashaba: He was very interesting person, and I hope someday someone will make an interesting movie about him, like, adventure movie. All about how he hide from Russian forces? I don’t know how to translate this. All across the globe. So he was running from them in London, in Egypt, in Jerusalem, and ended up in America.

Rachael Myrow: Intriguing, no?? Let’s step back in time to understand what exactly this man was running from. Born Andrii Humnytsky in what is now central Ukraine in 1832, this guy was destined to become an Orthodox priest like his father. He certainly caught the eye of the highest-ranking church leader in Ukraine at the time, a man named Metropolitan Philaret.

Jars Balan: The Metropolitan of the Orthodox Church in Ukraine at that time, Metropolitan Philaret, saw that this guy was smart and capable, and made him his personal assistant.

Rachael Myrow: That’s Jars Balan, a researcher at the Institute of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Alberta. He’s written the definitive research paper on our man Humnytsky, and he spoke at the unveiling of that plaque in Hayward. Balan says, from childhood, Humnytsky felt a fierce pride in his Ukrainian ancestry and his Christian spirituality. He took the monastic name Agapius, derived from the Greek word agape, meaning selfless love, and pretty much from the start, his politics leaned progressive.

Jars Balan: Because he got to travel around with the Metropolitan, he visited a lot of communities, and he was appalled by the poverty in these villages. This is still a time of serfdom, and the church even had serfs, and he found that appalling.

Rachael Myrow: The word SLAV is where English speakers get the word slave, because Slavs became synonymous with enslavement in the Middle Ages. A serf, for those of you not up on your Eastern European history, is an agricultural laborer bound to work on their lord’s estate. Humnytsky hated the practice.

Jars Balan: In fact, when he was [in] his first level of ordination, and he gave his ordination sermon, he called on the church to melt down all the gold and precious jewels, all the golden precious metals, and use the money to feed, to help the poor.

Rachael Myrow: Sounds Christian in the OG sense, but this talk did not go over well in mid-19th-century Ukraine. Still, Humnytsky would not cool his revolutionary jets. He got acquainted with – and radicalized by – locals who, decades before, were involved in a failed attempt to overthrow the czar, the emperor of Russia.

Humnytsky’s boss, the Metropolitan, saw trouble brewing, so he sent him out of the country. Because Ukraine was part of Russia at the time, he sent Humnytsky to serve in the chapel of the Imperial Russian Consulate in Greece. But there, too, Humnytsky fell in with like-minded revolutionaries. He started writing for a dissident journal called Kolokol. In English, The Bell.

After publishing searing articles calling for the emancipation of serfs and criticizing the Orthodox Church’s support for Tsarist autocracy, Humnytsky was arrested and imprisoned in the hold of the Russian warship, which set sail for what is now Istanbul.

Jars Balan: He managed to arrange an escape when they were holding him in Istanbul. He had an aunt who was in Moscow. She had some connections, managed to pull a few strings, maybe pay a few bribes.

Rachael Myrow: In his memoirs written decades later, the dissident priest recalled his optimism as a young man:

Voice actor reading from Humnytsky’s memoirs: “I escaped for an eternal glory, to be a Kozak in the free world.”

Rachael Myrow: Things didn’t quite pan out that way.

Rachael Myrow: In point of fact, this episode was just the start of a life on the run from Russian justice. Repeatedly over the years that followed, he’d pop up in a new location, work all sorts of odd hustles, and then the Russians would catch up with him. For instance, he had a facility with languages, so in London, he was a Russian language tutor to Greeks, and a specialist in old coins at the British Museum.

Jars Balan: How he picked up the specialty, I’m not sure, but I said he was a very bright guy and interested in history and archeology and theology and all kinds of things.

Rachael Myrow: It’s around this time that Humnytsky began using “Honcharenko” as his nom de plume. And – I mean, you can’t make this stuff up, this guy was extraordinarily bright – he picked up a craft – typesetting – that would come in handy later in his life.

Jars Balan: …in a printer shop and learned how to print. He translated a rare sort of, I think it was a 15th century book called Stoflau // calling for reforms in the Orthodox Church.

Rachael Myrow: Troublemaker, right? And remember, everywhere Humnytsky goes, he makes friends with anarchists, dissidents and revolutionaries. But he never lost his passion for spirituality. In fact, he returned to Greece for additional professional training.

Sound of monks chanting

Rachael Myrow: …on a remote peninsula in the northeast. It’s home to the largest monastic community in the world, a UNESCO World Heritage Site today, and an excellent place to hide from the Russians.

This meant Humnytsky was now able to lead prayers, conduct marriages and baptisms, and otherwise tend to lay people’s spiritual needs.

Humnytsky bounced around for years. Jerusalem, the mountains of Lebanon, Cairo, where he survived a knifing paid for by the local Russian consulate.

Not long after, he decided to make a break for the New World, quite likely because he wanted to put as much space as he could between himself and the Russians. In 1865, in his early thirties, he landed in Boston, headed to New York, then New Orleans. But even on this side of the Atlantic, local Russians would eventually figure out Father Agapius was not actually a Greek with remarkably good command of Russian.

Around this time, Andrii Humnytsky changed his name – not just his nom de plum – to Agapius, or Ahapi, Honcharenko, to avoid detection from the Russians.

Also, while in New York, he married the daughter of one of the Italian radicals he met in the U.S., a young school teacher named Albina Citi.

Jars Balan: Not to the liking, particularly of her family.

Rachael Myrow: Her deeply anti-religious family was put off by this…

Jars Balan: … bearded orthodox priest in wearing cassocks and things. But they were in love, and they wanted to go to the West Coast.

Rachael Myrow: So, in his mid-30s, Honcharenko landed in San Francisco with his wife, Albina. Remember how he learned about printing in London? He bought a set of Cyrillic fonts and launched the Alaska Herald — with a Ukrainian-language supplement. That was one of the very first Ukrainian publications in North America, and a must-read for Ukrainian expats from New York to Siberia. A must-read for a lot of Russian expats, too.

Jars Balan: He was successful in getting the paper going. He got funding from the American government initially.

Rachael Myrow: Here’s an excerpt of an issue celebrating the publication’s second year:

Voice reading from newspaper article: From the day of its birth it assumed a certain attitude, and it has unflinchingly maintained its position and consistency during these two years. It has struggled hard and bitterly because it was on the side of right and justice, and they who champion the oppressed seldom find their work either cheerful or remunerative.

Rachael Myrow: OK, so Honcharenko could get a little strident and self-aggrandizing…

Voice reading from newspaper article: Of course, it has encountered severe hostility at the hands of those whom it has exposed; of course, it has made enemies for itself by the score.

Rachael Myrow: The problem for Honcharenko was that he was a critic of imperial malfeasance wherever he saw it, and eventually, he bit the hand that fed him, none other than the U.S. government, a primary backer of the Alaska Herald.

Jars Balan: Because the administration that the Americans set up had problems with corruption. He was critical of the way the American administration treated Native people. He had some environmental concerns. When he became critical of what was going on in Alaska, they pulled the funding.

Rachael Myrow: Meanwhile, the Russian Orthodox Church relocated its U.S. base of operations from Sitka in Alaska to San Francisco in California. And it came to their attention that a renegade priest was holding services in the city. And that’s when the couple decided to decamp for Alameda County.

Rachael Myrow: Honcharenko sold his printing press, bought a 40-acre farm in the hills above Hayward, named the place “Ukraina,” and settled into a relatively calmer life for the next 40-odd years. He led weekly Orthodox church services on the farm for local and visiting Slavic immigrants, conducted baptisms, and weddings. The couple also gardened. They sent numerous samples of plants and vegetables to the editors of the California Horticulturalist and Floral Magazine, who wrote back to praise the “monster squash,” and “some of the finest sugar table corn and nutmeg melons we have ever tasted.”

Jars Balan: His life was amazing. He was eccentric, he was quirky. He had strange ideas about some things; there’s no doubt. But when you look at the trajectory of his life, it’s an amazing story.

Rachael Myrow: He continued to publish articles and even a memoir in 1894. His homestead became a stopping place for fellow countrymen passing through. For half a minute, a small group of dreamers tried a utopian colony on his land. The venture failed, but it burnished Honcharenko’s reputation and ensured his lasting memory in the Ukrainian diaspora.

Jars Balan: There are stories that say, no, no, he exaggerated or that he made up stories about his life and everything like that. He might have exaggerated certain things, but there are a lot of things that my research has shown actually were based in fact.

Rachael Myrow: The last years were hard. Their daughter died when she was just ten years old. The subsistence farming wasn’t enough to subsist on. But they’d given so much to so many over the decades, a lot of locals returned the favor.

Jars Balan: They were very poor at the end, and really dependent on the charity of ranchers in the surrounding community who took an interest in him and helped the two of them out in their last years. So his life wasn’t any easy life.

Rachael Myrow: Honcharenko died at the age of 84 in 1916, a little over a year after his wife. His death was front-page news in several papers, and his life inspired a couple of biographies, but it wasn’t until 1997 that the California Historical Resources Commission designated his ranch and gravesite a state historical landmark, and a couple years later, a cairn and plaque honoring Honcharenko were unveiled there.

Sounds from the celebration: Odyn, dva, tray. Slava Ukraini! Slava Ukraini! Hey, I want to hear it again! Slava Ukraini! Slava Ukraini! OK, that’s better.

Rachael Myrow: Back at Garin Regional Park, the group of Ukrainian-Americans we met at the start of this story takes a group photo, with the Ukrainian national salute that translates to “Glory to Ukraine!” This bucolic hilltop with its historic marker and park panels tells the broad arc: émigré priest, dissident publisher, gentleman farmer. Ukrainians here and abroad remember, but what about the rest of us? This whole story is certainly news to our question-asker, Tony.

Tony Divito: I think we’re incredibly fortunate and lucky to have him as part of Bay Area history. It goes with our history of allowing refuge, of allowing people from desperate situations to come here and thrive here and contribute to our community.

Rachael Myrow: His story was just, like, epic. Right? Like it’s, you know…

Tony Divito: It deserves, you know, a series. Like a television mini-series or an audiobook of some sort.

Rachael Myrow: Hit me up for the writers’ room, guys!

Olivia Allen-Price: That was KQED’s Rachael Myrow. Special thanks to Gabriela Glueck, who literally went the extra mile up that hill to help us report this story, and to Dan Brekke, who read Honcharenko’s archival writings.

Tony Divito sent in today’s question, and I want you to be like Tony! Head to BayCurious.org to submit a question you’ve been wondering about. We are always on the lookout for great questions and yours could be what we tackle on next! Again, head to BayCurious.org to ask.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Our show is produced by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

Extra support from Maha Sanad, Katie Sprenger, Jen Chien, Ethan Toven-Lindsey, Dan Brekke and everyone on team KQED.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by the Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price. See ya next time.