Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Morgan Sung: Okay. So a few weeks ago, my friend Candice Lim joined us on the show.

Candice Lim: Morgan, I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but I do think we are entering a recession culture era.

Morgan Sung: We ended up having to cut some stuff out of that episode, but I wanted to bring this part back because I can’t stop thinking about it.

Candice Lim: Do you remember back in 2016, 2017, there was this song called “Cut It” by OT Genesis and it became a dance trend. What’s funny is that I missed that boat, but the boat is back because a week ago, I opened my For You page and there are four white boys dancing in a Wayfair customized apartment and they’re doing 2020-esque TikTok dances. Can I play one for you now?

O.T. Genasis: Cut it, cut it cut it cut it

Candice Lim: So I think this video also alarms me because it does make me believe that white boy swag is back and white boy swag is a recession indicator. After this, I saw so many more videos of white guys trying to dance to the song. Please notice I said try. And I think that cut it getting revived on TikTok — it’s white boys trying to have a swag-a-thon. Sorry, producer just asked what does white boy swag mean, Morgan, please step in.

Morgan Sung: White boy swag, in this meme context we’re talking about here, is this phenomenon in which white teenage boys get really into dancing to hip-hop, and it seems to trend right before some kind of economic downturn, like how, in 2007, Soulja Boy released “Crank That (Soulja Boy),” right? That year, every suburban kid was doing that dance in a little snapback hat. That’s white boy swag. And then 2008, financial crisis.

Candice Lim: So here’s the deal. Morgan, I’m obsessed with recession indicators because it’s like a joke, right? Like for me to try to create correlation between white guys dancing on TikTok and the reason I can’t buy eggs, it’s stupid. But I like recession indicators because I think it’s really funny to talk about how the economy does affect culture.

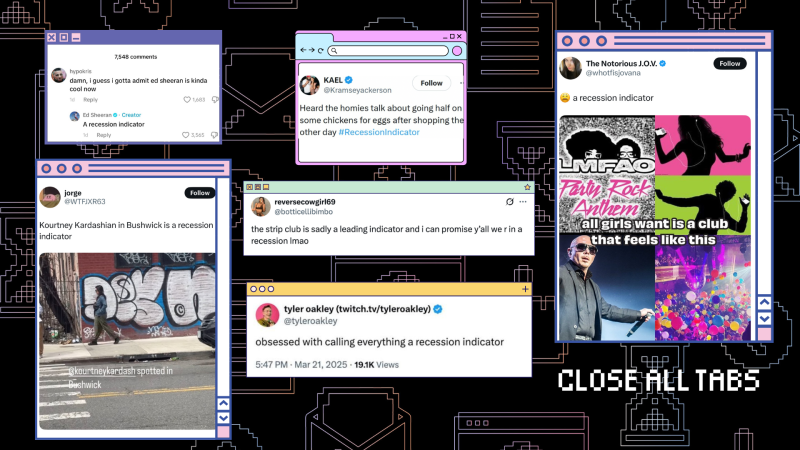

Morgan Sung: The stock market actually crashed days after recording that segment. And Candice is right. The economy and culture are inextricably linked. And while recession indicators have been a kind of online joke for the last few years, the meme is feeling a little too real. You may have seen some of these theories floating around on the internet, like how Lady Gaga is bringing back recession pop with her latest album, or how flash mobs are back in, and surely that’s a sign of economic downturn.

A lot of them are pretty silly. But some are actually grounded in reality and are based on changes to consumer spending. Like how press on nails are trending because manicures are an expensive luxury. It seems like every aspect of internet culture right now could somehow be a recession indicator. But when did this meme actually start? And at this point, what isn’t a recession indicator?

This is Close All Tabs. I’m Morgan Sung, tech journalist, and your chronically online friend, here to open as many browser tabs as it takes to help you understand how the digital world affects our real lives. Let’s get into it.

Let’s open a new tab. What are recession indicators?

To be clear, recession indicators are not just memes.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: Hey Morgan, I’m Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí. I’m a reporter here at KQED News, and you know, when I saw the recession indicator kind of make a comeback, and people really just labeling many ridiculous things recession indicators, I absolutely loved it. And I wish I had this when I was studying recessions and economics back in college.

Morgan Sung: Carlos actually has a degree in economics, which came in handy when he reported on recession indicator memes for KQED, where this podcast is produced.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: So I think the most useful place to start is first defining what a recession is. For economists for a long time, what they would look at is if we had two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. So a couple ideas that we need to unpack there. So first off GDP, that’s the total amount of goods, of services that is produced consumed by a country, right? So if that number shrinks… that means that people are consuming less, producing less. So there’s just less dollars moving through the system. What economists do is that they measure GDP, that total number, four times a year, every quarter. So, we already went down twice. That is the technical definition of a recession.

Morgan Sung: But GDP alone doesn’t account for other signs of economic health, like unemployment and investments, and importantly, how consumers are feeling about the economy. These other factors are all recession indicators, including consumer confidence.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: The idea of consumer confidence. That tells us how consumers, like you and I and folks listening to us, how they feel about the future of the economy. Because how you feel about the future the economy will influence your personal decisions of whether you wanna start a business, whether you want to buy a car, a home, or even plan a family.

Morgan Sung: The meme may be a modern phenomenon, but theories about cultural recession indicators have been around for decades. Like the Hemline Index from the 1920s and the Great Depression. It claims that skirt length is correlated to economic health. When the economy is doing well, skirts get shorter. But when the economy’s doing poorly, like during the Great Depression, fashion trends are more modest and skirts get longer. That theory has been debunked, but others are a little more convincing since they revolve around how people are spending their money. Like the lipstick index of the early 2000s, which claims that during recessions, women are less inclined to spend money on big ticket purchases like designer bags or nice jackets. Instead, they’ll buy affordable small luxuries like lipstick.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: So if lipstick sales go up randomly, that means that the economy is slowing down, right? Because consumers feel less confident. That’s going to affect what they buy, what they look for.

Morgan Sung: Okay, so that’s like a traditional economics definition of a recession indicator. But we’re talking about internet culture here. So where did this meme come from? We have to go all the way back to 2019. A Twitter user who goes by Lit Capital posted screenshots of news articles that all warned of impending economic doom from declining RV sales to Bitcoin trends to an uptake in the price of a Popeye’s chicken sandwich. Along with the screenshot, they posted “When did everything become a recession indicator?” That’s when people started jokingly referring to trends as recession indicators. Let’s fast forward to 2022. A dancer who goes by Botticelli Bimbo tweeted, “The Strip Club is sadly a leading indicator and I can promise y’all we are in a recession.” And that became known as the stripper index. If the strip clubs are empty, we’re screwed.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: If people feel nervous about the economy, they feel like, “oh shoot, am I gonna lose my job?” They might pull back and spend less on things that they may see as frivolous or as extra costs, right? Consumers drive the U.S. economy.

Morgan Sung: And in the years since, so-called recession indicators have sprung up again and again, from theories about bleach blondes going back to their natural hair color to save money, to the resurgence of Y2K fashion and early 2000s dance music that was trending before the last recession.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: So I think that when we think about things like recession pop, it’s less about the, you know, if there’s a correlation or causation between certain type of pop music and the economy, but rather it says a lot more about us and about how we experience the economy and how we create certain benchmarks in our mind of how time passes, right? We’re like, “oh yeah, that’s, you now, my parent got laid off back then. And also, you know, my favorite Lady Gaga album came out.” Humans are really good at finding patterns. And when folks don’t have access to, you know, like the super complex economic data that economists are looking at, we’re gonna try to make, you know seek the patterns out with the data that we have at hand.

Morgan Sung: Yeah, so if Soulja Boy comes back, we’re screwed.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: Exactly, exactly.

Morgan Sung: As economic anxiety ramped up, so did the theories about these cultural recession indicators. The meme really took off late last year in the aftermath of the election. According to economists, we weren’t necessarily headed for a recession, but the vibes were bad and consumers were nervous and recession indicators seemed more real than ever.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: If people are nervous about something, they’re gonna talk about it more on social media. And a few of the economists I spoke to, what they cautioned was, you know, it’s one thing to talk about the recession, but it’s another thing if, you now, people, every time they go on social media, they hear their friends, or all these things about recession, it kind of actually starts going into your head, and you’re like, “Oh, yeah, huh, the economy is slowing down, the economy’s slowing down. You know what? Maybe this weekend, I don’t go to the movies, or maybe I don’t go out to eat anymore. I’ll just pack my own lunch.”

So it kind of becomes a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy where people hear “recession, recession, recession” all the time. That’s gonna influence their behavior. They’re gonna spend less. That’s less money moving through the economy, less consumption, and stronger probability of a recession. So it’s interesting that memes can actually signal consumer confidence as well. And if it’s low or if just people are nervous, then it just makes the signs of a recessions bigger and stronger.

Morgan Sung: So, are recession indicator memes a recession indicator?

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: I think… I think there’s a pretty good argument to say that they are.

Morgan Sung: Earlier this month, President Trump announced sweeping tariffs on 90 other countries, stoking a trade war and rattling the economy. The stock market tanked, Google searches for recession spiked, and suddenly the recession indicator memes blew up. Anything and everything could be a sign of another recession. And after the tariff announcement, it seems like the joke wasn’t a joke anymore. So how did spending and consumer confidence change during the last recession? More on that after this break.

Let’s get back to the story. So most of the more grounded recession indicator theories, like the rise in making matcha lattes at home instead of buying them at trendy cafes, are really about the spending habits of a particular group of people. Let’s talk about that and how the economy is intertwined with culture in a new tab. Recession… consumer… culture. We’re diving into this with an expert who studies the intersections of culture and economics.

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett: My name is Elizabeth Currid-Halkett and I am professor of public policy at the University of Southern California.

Morgan Sung: And the author of several books. Back in 2017, she wrote a book called The Sum of Small Things. In this book, she examines the habits of the tote bag carrying, green smoothie loving, public radio listening consumer, a group she calls “the aspirational class.”

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett: The aspirational class are different in the sense that they are meritocrats. They tend to be highly educated and they also tend to have higher income. We know education and income tend to go hand in hand for the most part. And they also, and I think this is the thing that makes them kind of an unusual new kind of class of people, which is that they constantly aspiring to some better life and that better life might be you know, really what we now call wellness. You know, it’s their how they exercise, how they eat, you know their relationship to the environment, their impassioned view towards social justice and equality. All of these things, by the way, are very laudable. But I think it’s this idea that it is still quite self-focused.

Morgan Sung: Yeah. A lot of the so-called recession indicators that we’re talking about in this episode really have to do with consumption and spending habits, but in your book you lay out the difference between conspicuous consumption and inconspicuous consumption. What is that difference?

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett: You probably already know the term conspicuous consumption, which is this idea that we buy consumer goods to in an overt way to show our status. So think about like a Rolex watch or a handbag with lots of logos, okay? That’s like classic conspicuously consumption. Like you don’t need a Rolex watch, like a plastic Timex watch will be perfectly fine. You know, we buy things that basically, functionally speaking, are not better, but they show status. Inconspicuous consumption is actually very hidden, except for people who are in the know.

And I found that right around the recession of 2007 through 2009, that, you know, the top income groups, their conspicuous consumption tanked. But instead, they were spending all this money on like gardeners and, child care and education and health care, all of these things that you can’t see but are really expensive. So, you know, a college tuition, for example, is way more expensive than, like, the lease on a BMW car. One you can see and the other is really obvious, but both are really about status in different ways.

Morgan Sung: You wrote The Sum of Small Things back in 2017. How have the markers of the aspirational class changed? Have they changed since then? And has it been influenced by the state of the economy?

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett: Think it’s actually gone on steroids. So when I wrote The Sum of Small Things, I was thinking a lot about inconspicuous consumption. I was observing it anecdotally. And what I’ve actually found since is that a lot of that stuff has become more expensive. We know that private schools, colleges, even exercise classes, and then wellness in general exploded. And I see wellness for the most part as something that’s quite an expensive luxury to engage in wellness as a phenomenon.

And even something like, you know, in Los Angeles, we have this store called Erewhon, like that didn’t exist when I wrote about The Sum of Small Things, but literally Erewhon encapsulates everything about the aspirational class. You know, it’s this really expensive, organic wellness, like tonics and milkshakes and organic, humane meat and all the things. And it’s like in this one-stop shop, and it also ties into other things like fitness and well-being, not just simply food. So it took Whole Foods and was like, let’s just layer on what you need at the yoga studio as well.

Morgan Sung: I know, those celebrity smoothies, they get you.

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett: Well, I mean, it’s amazing because they’re like $30 each, and you’re just thinking, who spends $30 on a smoothie? It turns out lots and lots of people. There’s a long line.

Morgan Sung: The Erewhon smoothie line is impossible. So we’ve talked a lot about these kind of silly recession indicators that may or may not be based in reality, but how are culture and consumption habits and the state of the economy intertwined according to your research?

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett: As someone who has spent my entire career studying culture in one way or another, I believe it explains an awful lot, although it’s so hard to put your finger on what it is. But think about it like this. First of all, for the most part, when there’s a recession or a fear of recession, most people on some level are wary, right? I mean, I guess maybe if you’re super, super, super rich, you’re not as worried. But most people start rethinking purchases because they’re like, “Maybe it’ll be my job. Maybe my stock’s going to go down.” Whatever, there’s all sorts of things.

So you’ve got a recession, impacts consumption, but recessions impact culture, too, because they can impact people’s emotional, psychological states. And we know that that is intertwined in culture. I mean, think about how different cultural production would have been or the cultural sensibilities would have in the roaring 20s versus the Great Depression. Like, it’s just different. And then that of course changes how things are produced and then it changes how people choose to consume things. So they’re always intertwined and I think probably the larger through-line there is that there’s a kind of an emotional mood associated with a moment in time which permeates through these different areas.

Morgan Sung: Absolutely. Do you have any recession indicators? Like, you know, these kind of like meme-y ones, silly or not real or not? Is there anything to you that says, “Ooh, we’re like the economy is bad.”

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett: Oh my gosh. You know what? It’s so funny. I was actually thinking about that. I think when you can get a table at a really hot restaurant easily, that maybe there’s something going on. Because it’s so gratuitous. Like no one needs to go to a really trendy restaurant. So if suddenly people are worried about money or having their job, probably that’s one thing that might go. And so that’s what I think. If you easily get a table at a trendy restaurant may- maybe that’s a harbinger of you know, tough economic times.

Morgan Sung: Like we heard from Elizabeth, consumer habits run deeper than just buying things. So not every shift in spending trends is proof of a recession. But at the same time, the vibes are bad right now. And trying to find explanations for things that make us anxious, like the economy, can be comforting. It’s also fun. We’ve gone into some of the viral recession indicators, but they’re not universally held beliefs. Everyone has their own theories and their own hot takes. We’re going to hear a few of those takes… in a new tab. Other recession indicators. So I reached out to a few people who all cover the internet or culture in some way and asked them for their recession indicators, and more importantly, why they think they’re recession indicators.

Christiana Silva: My personal recession indicator is that TikTok wants me to host a dinner party and I can’t afford to do that. I could host a potluck and I could go to a picnic, but there’s this like quiet luxury of a dinner where none of your friends bring side dishes or bottles of wine and you provide everyone with three courses of food and centerpieces with fresh flowers and tapered candles. It’s just not in my economic future. Like the bougiest thing you can do is have raspberries and eggs in your fridge? That can’t be good.

Tanya Chen: It is not a joke. A real recession indicator has been that I’ve taken up chain smoking. I am a member of the media kind of just trying to stay afloat and I’ll have the occasional cigarette and joint to help kind of ease the stress of it all right now, but I’ve lately just been chain smoking, like my Chinese ancestors would be both proud and disappointed to know. And it is what it is. It is the realest recession indicator of this moment in time and in my life.

Moises Mendez II: I think that the Tumblr aesthetics revival is such a recession indicator, and Addison Rae is like the leader of this Tumblr aesthetics revival because of so many references in her music. Like just using wired headphones, I don’t know why that’s so revolutionary, but it’s just like, that’s such a pointed choice and I love it, I think it’s so fascinating. Like there’s so many different things of people wanting that simplicity again. And I think that that’s a recession indicator.

Daysia Tolentino: My recession indicator is Domo making a comeback in the US. For those who are unfamiliar, Domo is a cute Japanese monster and he has a square brown body and sharp triangular teeth. He rose to prominence among kids my age during the last recession because he was on Nickelodeon. It was recently announced that he was returning in 2025, which immediately set off my recession indicator alarm bells.

Sarah Vasile: So, historically, in the sports world, a Phillies World Series victory has been a recession indicator. And the last time that they actually won was in 2008. We all know what happened then, but they’ve had a string of winning seasons. I do think it is somehow related to how significant Pennsylvania’s impact is when it comes to the Electoral College. So if you want a healthy economy, you just have to pray that raw milk poisons Bryce Harper, I guess.

Aidan Walker: Calling in to share with you a recession indicator I’ve stumbled upon on X, the everything app. It is a deep fried image, a selfie of a guy sitting in a car. You know, all the distortion is kind of turned up to max. And to the extent recession indicator just means any piece of culture that’s giving, you know, peak millennial ascendancy type of vibes, peak recession vibes, this definitely fits into it. You know deep fried memes from a specific era of the internet. And that post has 129,000 likes, so maybe it means something.

Jen Chien: Over Easter weekend, my friend sent me several links to articles about using potatoes instead of eggs for Easter. One of them was a delicious — “exclamation point, exclamation point, exclamation point” — recipe for deviled potatoes and really had this vibe of, “it’s so exciting to eat deviled potatoes. It’s a hack. It’s something delicious that you will want to do year after year.” And then several articles about dyeing potatoes for Easter instead of Easter eggs, and also with a vibe of trying to get you really excited. One of the subheadings on one of the articles said, “why you’ll love dying potatoes for Easter,” and I thought, ooh, we’re in trouble.

Morgan Sung: Joking about recession indicators might make coping with this existential anxiety just a little bit easier. It’s human nature to notice patterns and like we talked about, the economy does influence culture. But that doesn’t mean that every trend is somehow a recession indicator. Just take it from Carlos, who investigated his own theory after a night at the club.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: I noticed that there were a lot more people walking around the club with blue drinks, which is an AMF, and it’s a blue drink because it has blue curacao. It has like five, seven types of liquor. And you can get it for the same price as any other cocktail, but it’s really strong cocktail. So then, you know, my friends were like, “Well, it’s probably because people are trying to save money.” And in my head, I was like, “is this a recession indicator?”

I did reach out to multiple liquor distribution companies. And one of them did confirm with me that yes, they’ve seen an increase in blue curacao sales. And then I’m like, okay, well now second step, let’s talk to owners of the biggest clubs in San Francisco, see if they are noticing this too. And the ones that got back to me said, “no, they’re kind of like the same. We’re not seeing a spike.” So my theory was kind of disproved or didn’t have again the data I needed to keep moving forward, but it goes to back we’ve been talking about, that we notice the things that we’re most familiar with. We notice something that’s really important or just relevant to us and then we connect it with other things that we maybe associate with it subconsciously, right? Like a Dunkin Donuts closing, we are like, “Oh my gosh, you know, economic hardship.” Uh, Lady Gaga. “Ah, 2008. Ah! Like, losing Homes.”

Morgan Sung: Peplums back in.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: Exactly.

Morgan Sung: Office wear at the club.

Carlos Cabrera-Lomelí: Yeah, true. That’s, hey, great reporting happens at the club.

Morgan Sung: Special thanks to Cristiana Silva, Tanya Chen, Moises Mendez II, Daysia Tolentino, Sarah Vasile, Aidan Walker, and Jen Chien for sharing their recession indicators with us. Let’s close all these tabs. Close All Tabs is a production of KQED Studios and is reported and hosted by me, Morgan Sung. Our Producer is Maya Cueva. Chris Egusa is our Senior Editor. Jen Chien is KQED’s Director of Podcasts and helps edit the show.

Original music and sound design by Chris Egusa. Additional music by APM. Mixing and mastering by Brendan Willard and Katherine Monahan. Audience engagement support from Maha Sanad and Alana Walker. Katie Sprenger is our Podcast Operations manager. And Holly Kernan is our chief content officer.

Support for this program comes from Birong Hu and supporters of the KQED Studios Fund. Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by the Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, San Francisco, Northern California Local.

This episode’s keyboard sounds were submitted by Alex Tran and recorded on his white Epomaker Hi75 keyboard with Fogruaden Red Samurai keycaps and Gateron Milky Yellow Pro V2 switches.

If you have feedback or a topic you think we should cover, hit us up at CloseAllTabs@kqed.org. Follow us on Instagram @CloseAllTabsPod or drop it on Discord. We’re in the Close All tabs channel at discord.gg/kqed. And if you’re enjoying the show, give us a rating on Apple podcasts or whatever platform you use.

Thanks for listening!