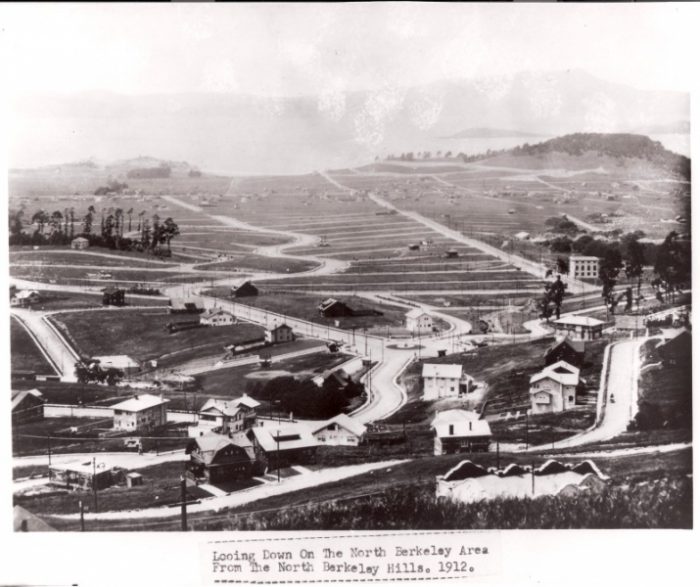

President Trump has made protecting the suburbs from low-income housing part of his reelection campaign. But this idea — that middle-class families should be kept separate from the poor and working class — has been around for a century, and it’s had profound impacts on our housing supply, affordability and racial inequity.

It’s a topic we’ll unpack in KQED’s upcoming podcast, SOLD OUT: Rethinking Housing in America.

We have been reporting on how California’s housing crisis has been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. We’ve talked to unemployed workers worried about eviction, covered rent strikes and tracked the state’s plan to house people experiencing homelessness.

The coronavirus has exposed just how precarious and inequitable America’s housing system has been.

Nearly 11 million U.S. renters, or one in four, spent more than half their incomes on housing in 2018; that was when the economy was considered healthy. In California, it’s one in three. As a nation, we are not building enough. That’s according to Freddie Mac, which estimates we need 370,000 more units each year to keep up with demand. The mortgage corporation also says 29 states have a housing deficit. And California is the epicenter of this housing crisis.