My earliest memory of my maternal grandmother is in a kitchen that I can just barely picture. It's far too large and blurry at the walls, which are dim and milky white. The table in front of me comes into focus, along with my grandmother's hands. She is making tortillas, flattening balls of dough with a rolling pin and then quickly transferring a disc of flour and lard from hand to hand before depositing it on a hot plancha. The finished tortilla lands in front of me. My little hands bring it to my mouth as the memory fades. Before disappearing, this brief image has communicated volumes about who I am and where I come from. It is my family's immigrant experience encapsulated in a single tortilla, passed from my grandmother's hands, which repeated these gestures countless times over the decades, preparing the staple that nourished her ten children and, when we were lucky, their children as well.

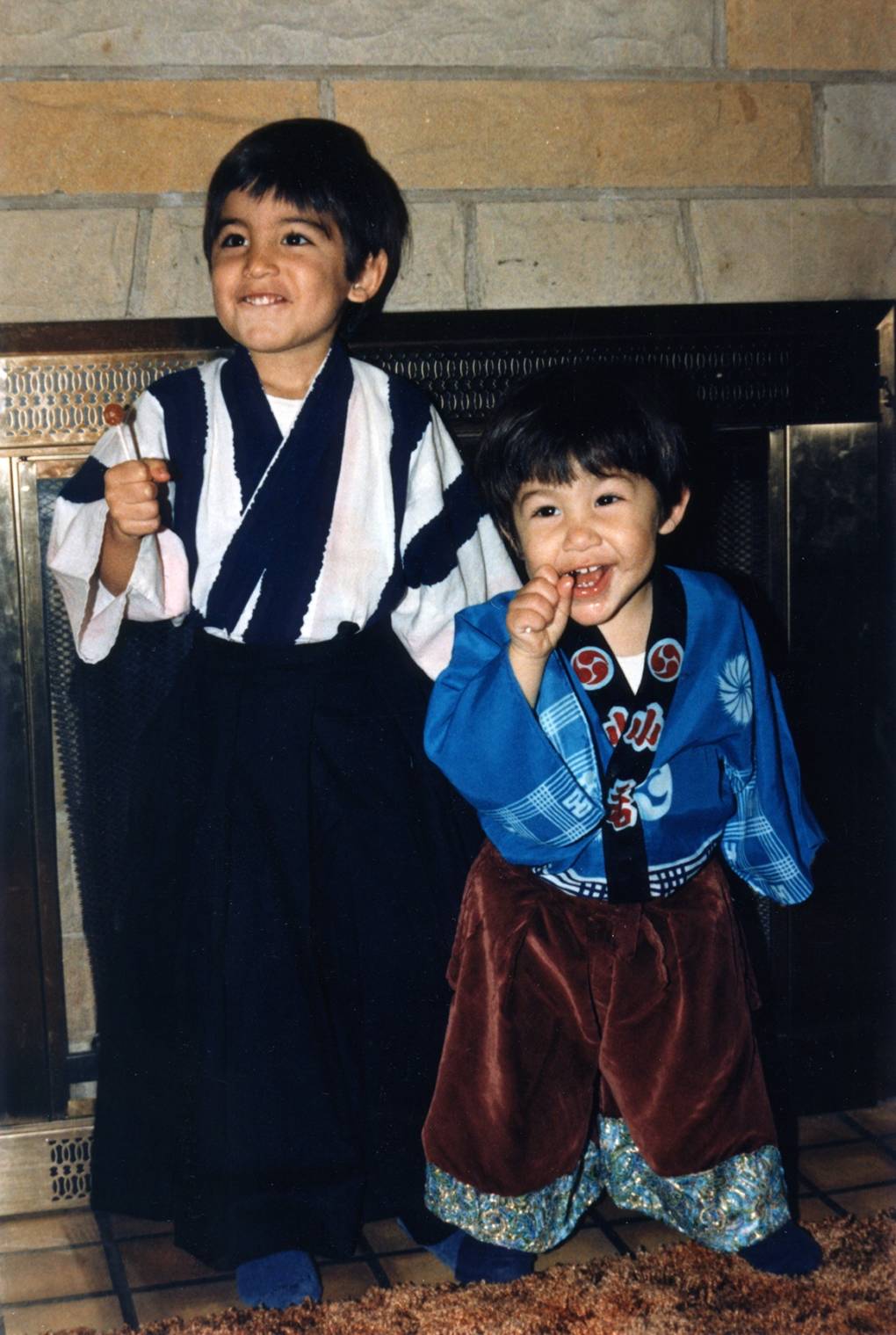

As 88-year-old Eva Hashiguchi prepares the many dishes that populate her annual Japanese New Year party, I couldn't help but flash on the above image of my own grandmother. These rituals are about more than just the acquisition and combination of ingredients, they are a complicated dance that involves the whole body in the offering. In Matthew Hashiguchi's film, Good Luck Soup, which takes its name from the centerpiece dish of Eva's annual family celebration, this meal is the site of more than just cooking and eating. Matthew and his extended family have been sustained by their matriarch's relentless positivity, but also shaped by a defining trauma without which their family may never have come into existence.

Good Luck Soup is one of just a few food-related films screening at this year's 35th annual CAAMFest, put on by the Center for Asian American Media, which runs March 9-19, 2017 and features 113 films from around the globe at various Bay Area locations. As usual, the festival is kicked off by the CAAMFeast, a celebration of Asian American culinary achievement on March 4, 2017. Each year, the Feast acknowledges the contributions of a trio of chefs and food organizations. This year, alongside the Asian Chefs Association and People's Kitchen Collective, the feast honors chef Roy Choi, whose Kogi fleet of L.A.-based Korean taco trucks is credited with kicking off the current food truck phenomenon. Choi's signature Korean BBQ taco is a quintessentially Los Angeles invention, famously representing the city's diversity through taste and giving voice to a certain part of the immigration experience.

The CAAMFeast annually celebrates the centrality of cuisine to culture and identity. This year's food-related selections elaborate the complicated issues surrounding the immigrant experience, taking on added relevance in the current political climate. The kitchen is so often the site where individual flair meets family tradition. Flavors melt but remain distinct. Immigrants may arrive and assimilate other aspects of their original cultures, but taste persists. Food defines.