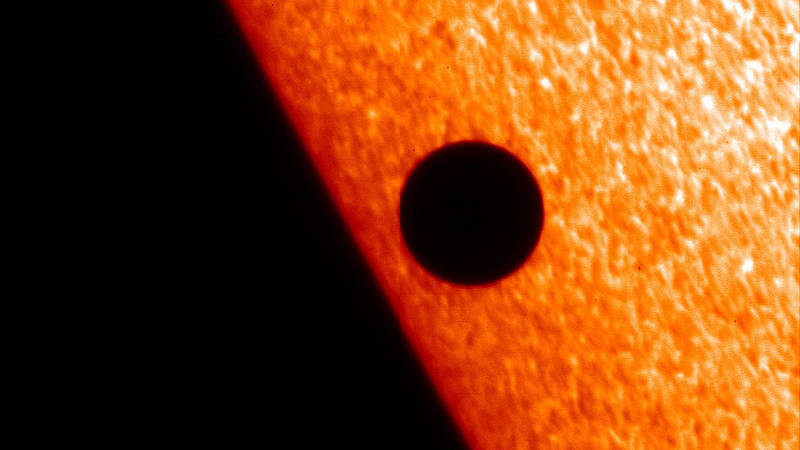

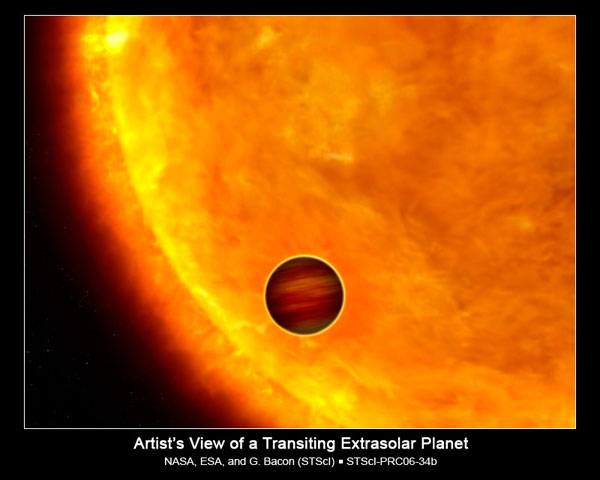

On Nov. 11, a rare and awe-inspiring astronomical event will take place in our skies: The planet Mercury will cross directly between Earth and the sun, appearing in silhouette against the sun’s bright face.

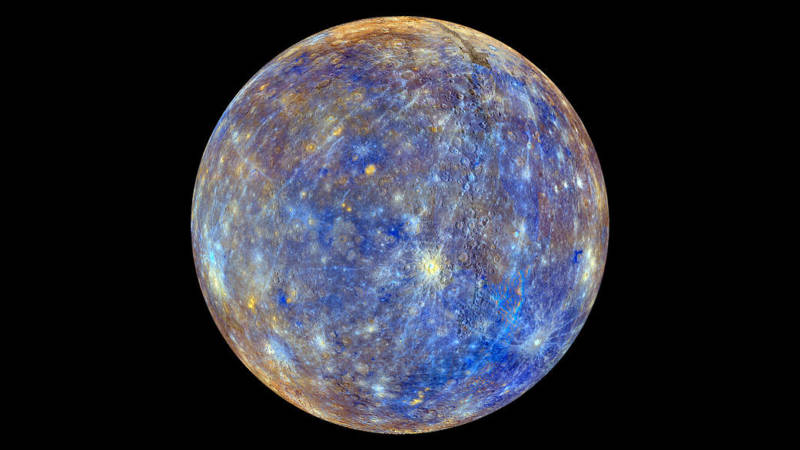

Remember Mercury? That elusive, scarcely seen, rarely talked about and smallest of planets in the solar system? The Nov. 11 event will place the tiny planet in the spotlight for several hours and give us all something to talk about.

The event, called a Transit of Mercury, occurs at intervals measured in years and decades. On average, the planet transits only 13 times a century.

The last one happened on May 9, 2016. The next isn’t until Nov. 13, 2032—and that one won’t be visible from North America. The next one that people in the San Francisco Bay Area can see won’t take place until 2049.

When to Observe

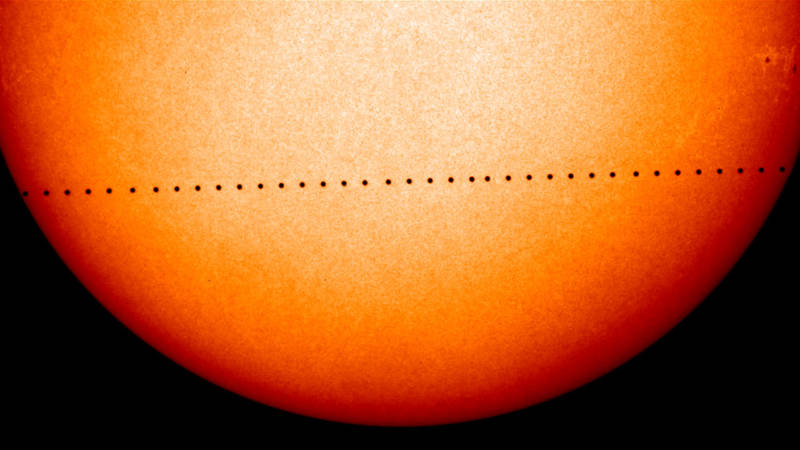

This year’s event begins on Monday Nov. 11 at 4:35 a.m. PST, when Mercury makes first contact with the sun’s limb and begins its crossing. Technically, there are two moments of contact between Mercury and the sun at the beginning of the transit. Contact I happens when the leading edge of Mercury’s disk first coincides with the limb of the sun. Contact II is the moment Mercury’s trailing edge crosses the solar limb and the planet’s silhouette becomes a complete circle against the sun’s backdrop.

The midpoint of transit is at 7:20 a.m. PST. On the Nov. 11 transit, Mercury’s path slices almost directly through the middle of the sun’s disk, so at midtransit it’ll be possible to find the planet at almost dead center.

Transit ends at 10:04 a.m. PST when Mercury departs the sun and returns to the backdrop of space. The discrete moments that Mercury’s disk begins and ends its crossing of the solar limb are called Contact III and Contact IV.

From the San Francisco Bay Area, the transit will already be in progress when the sun rises at 6:45 a.m. PST. The sun may not be immediately visible if there are buildings, trees or hills on your eastern horizon, but don’t worry. When the sun finally rises above all easterly obstructions, Mercury should still not have reached midtransit, and you’ll have a good three hours to enjoy the show.