Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: I want to talk about architecture for a moment – specifically residential architecture. In San Francisco.

You expect to see stately Victorian homes with their bright colors and fancy decorative trim.

Then there’s Marina style homes with their big windows and stucco facades.

But sprinkled in amidst these grander homes you might spot a few tiny cottages — the original tiny homes.

Charity Vargas: I did see two over in the sunset. There was like two close together and I thought maybe they might be them, but I’m not sure.

Olivia Allen-Price: Charity Vargas, our question asker this week, has seen some of these small dwellings dotted around the Richmond and Sunset districts near her home. And she’s heard that the cottages are holdovers from the Great 1906 earthquake and fire, but wants to know more.

Charity Vargas: How many earthquake cottages are left and you know, are they still used and where they are?

Olivia Allen-Price: Today on the show, we’ll dig into the history of San Francisco’s earthquake cottages. We’ll learn how critical they were in sheltering a vulnerable…but vital.. population and learn about modern efforts to save them. I’m Olivia Allen-Price and you’re listening to Bay Curious. Stay with us.

Sponsor message

Olivia Allen-Price: We set out to answer Charity’s question by searching for “earthquake shacks”…tiny homes built out of redwood and cedar after the 1906 earthquake and fire. Bay Curious editor and producer Katrina Schwartz found one high on a hill in Bernal Heights.

Joan Hunter: You want a little tour? Ok, this is our tiny kitchen and I believe this rectangle room is the original earthquake shack and this part is added on, but it’s kind of hard to say exactly. I’m Joan Hunter. I live in Bernal Heights, San Francisco, California in an earthquake cottage or earthquake shack, as some would like to say.

Katrina Schwartz: I’m standing with Joan in her light filled living room…all that’s left of the original cottage. It’s a modestly sized room, but has tall ceilings and windows that look out over a sweeping view of San Francisco.

What started out as a one room cottage has been expanded quite a bit…it’s about 620 square feet now, still small by modern standards.

Joan Hunter: Okay, so this is a little bedroom we have in the front and all of our rooms, this is a theme for the house, everything is small, very, very small.

Katrina Schwartz: Joan’s got two kids…so the house can feel like a tight squeeze at times. But she fell in love with the history of the place.

Joan Hunter: what I do know is that the guy who bought it, he was a little kind of like a bachelor. And he met someone who was also single and they moved together and they got married. And it was just a love story.

Katrina Schwartz: Joan likes thinking that after they survived the worst natural disaster San Francisco has ever experienced…and been homeless for months because of it…that they finally found some tranquility here, a little piece of San Francisco to call their own.

Music to help us transition

Katrina Schwartz: The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire leveled 80 percent of San Francisco. The morning of April 18, 1906 Bay Area residents awoke early in the morning to a temblor they’d never forget.

Sounds of shaking

Kathleen Norris: Every picture on the wall is going tack, tack, tack. Everything movable in the house is keeping up that unearthly clatter. You could hear up and down the roads, earthquake. It’s an earthquake. Oh, God help us, it’s an earthquake. of course, it changed the world for all of us.

Katrina Schwartz: Kathleen Norris shared her oral history with the Bancroft Library in 1960. There was no audio recorded during the disaster, but anyone who survived it remembered the trauma of it clearly…even fifty years later. Kathleen was in Mill Valley when the earthquake hit…where the damage wasn’t too bad. But she and her brother were curious about how San Francisco had fared…so they found a boat that took them to the city.

Joan Hunter: It was something to see. The great, heavy, slow rolls of smoke that were joining hands as they went up.

Katrina Schwartz: Kathleen describes refugees fleeing homes that had been leveled, toting their belongings in baby carriages and wheel barrows.

Kathleen Norris: We walked over the hot, hot rocks of Market Street. And of course, the cable car lines were twisted hairpins. And the houses were all down. There was nothing saved. Nothing was accepted.

Katrina Schwartz: And yet, the image that lingered in her mind…even as the smoke lay heavy over the hills… was of people getting to work to repair their city.

Kathleen Norris: And already there were people helping out and organizing, scraping bricks. The bricks were hot. And they were working away. Nobody felt for an instant, oh, let’s go somewhere else. Everyone knew that the city was going to come back.

Katrina Schwartz: As indeed it would. Just nine years after the earthquake and fire, San Francisco hosted the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition…the reason the Palace of Fine Arts was built…a spectacle that 18 million people visited by the time it closed.. Headlines trumpeted the achievement.

Voice over reading archival newspaper headline:

Big Fair is Opened. All eyes on San Francisco. President Flashes Signal

Fair Draws Myriad; All Records For Crowds Fall

Marvelous Exhibits From All Parts of the Earth Assembled by 42 Countries for the Hugest Conclave of Nations in History

Katrina Schwartz: It was a signal to the world that San Francisco was still the most important city in the West…one full of invention and achievement.

Voice over reading archival newspaper headline: Tower of Jewels Wreathed in Flames. But it’s only to thrill visitors

Art Smith Sets Hearts Leaping: Aviator’s Loop-the-Loops at Night Traced By Trail of Smoke

Katrina Schwartz: But how did San Francisco go from the absolute devastation of 1906 to showing off the latest advances in science and art on the world stage just nine years later? This is where the earthquake cottages… or shacks as they’re affectionately called…come into the story.

Woody LaBounty: So after the 1906 earthquake and fire, more than a quarter of a million people are at least temporarily displaced.

Katrina Schwartz: Woody LaBounty is President and CEO of San Francisco Heritage, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving San Francisco history.

Woody LaBounty: And now, the powers that be have to decide not only how to take care of all these people, but also who’s gonna rebuild the city?

Katrina Schwartz: Immediately after the earthquake and fire, the military stepped in and established tent camps in the city’s parks. But soon a new organization…the San Francisco Relief Corporation…was formed to distribute food, clothes and other aid.

Woody LaBounty: That covered many aspects of what you have to do when people are refugees, but also a specific housing effort, and that was the earthquake relief cottages.

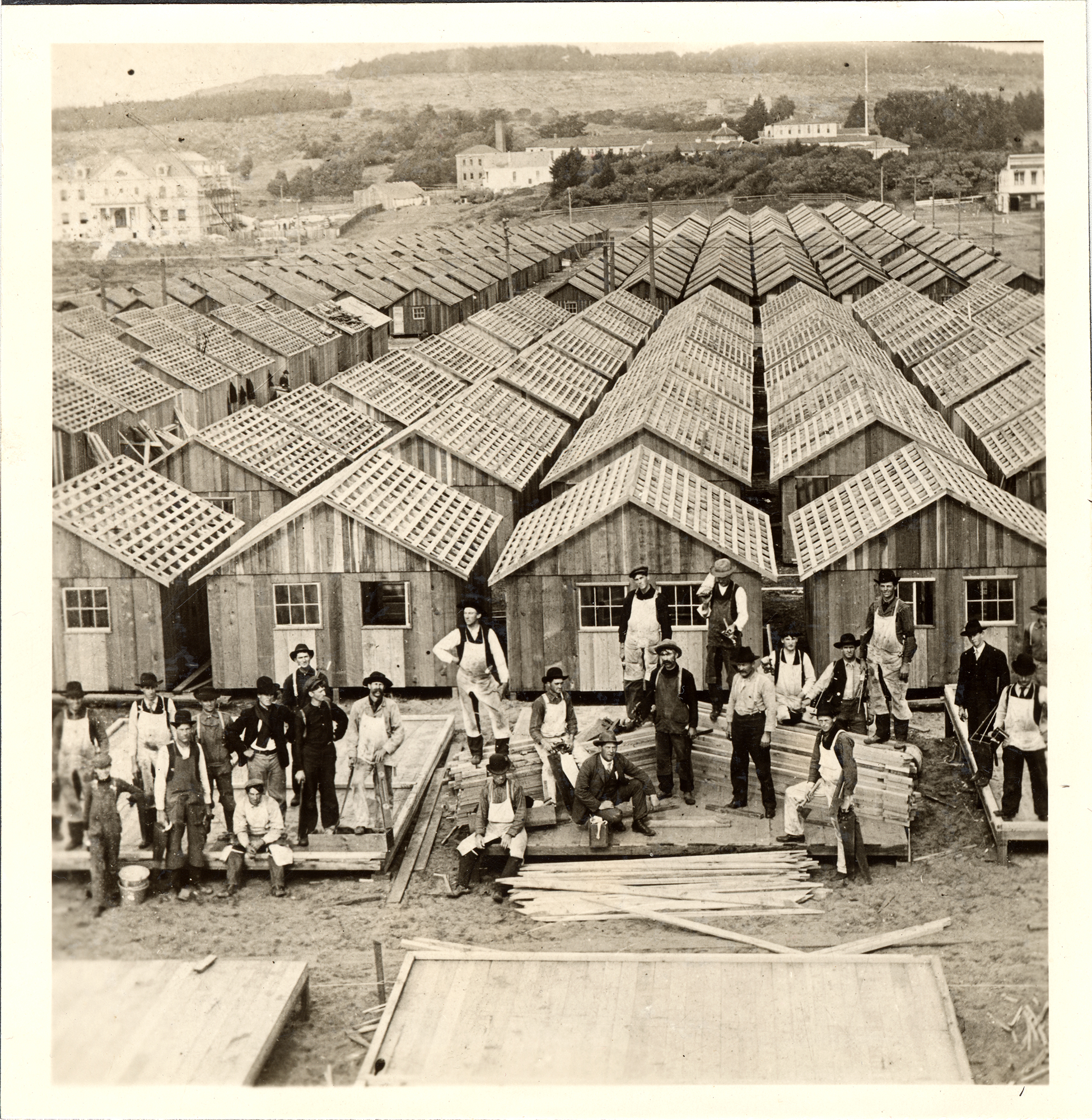

Katrina Schwartz: Officials were worried about sanitation in the tent camps when winter rains came. So, they decided to build 5,610 relief cottages…built with redwood, fir and cedar… to house people. They were painted “park bench green”…literally the color used on Golden Gate Park benches… and clustered in neighborhood parks like Jefferson Square, Precita Park, and Portsmouth Square. Around 17,000 people lived in them.

Woody LaBounty: If you owned property or you had a property that had been destroyed in the earthquake, you rebuilt or you figured out a way to move on. But there was a vast number of people who didn’t have any other resources.

Katrina Schwartz: These were San Francisco’s poor, folks who had lived in boarding houses or shared rooms downtown before the fire. City leaders wanted to keep these laborers with the skills to rebuild the city close by. But they didn’t plan to give away the cottages for free.

Woody LaBounty: So for all of wanting to take care of the refugees, there was also a fear at the time of creeping socialism. People in power did not want to give anybody anything for nothing. So they thought it would create indigence. And so you were supposed to pay some sort of rent.

Katrina Schwartz: Here’s how it worked. Shack residents paid monthly rent of a few dollars while their shacks were in the parks. But the relief corporation returned that money when a resident bought some land and moved the shack out of the park and onto their own property.That generosity was spurred by pressure to move refugees and their cottages out of the parks as soon as possible.

Woody LaBounty: As other San Franciscans were ready to move on from the disaster, they didn’t like the idea that their parks had a community, a village of working-class people. Living in the middle of their park. They wanted their parks back.

Katrina Schwartz: About a year and a half after the earthquake, in the summer of 1907, most of the shacks had been removed from the parks. Newspapers at the time described the surreal image of tiny homes on wagons moving across the city with people still in them.

Voice over reading archival newspaper excerpt: It is a strange sight to see a procession of these refugee cottages moving down fashionable Van Ness Avenue or busy Fillmore Street, faces peering from the windows, and men, women and children going about their household tasks as if their little home was securely perched upon a cement foundation and surrounded by a garden and a fence.

Katrina Schwartz: Back in 1907, the Richmond District, a northwestern neighborhood, was mostly undeveloped sand dunes, with lots of empty land. So many shack owners moved their cottages to vacant plots there.

Woody says the earthquake shack program not only got the city working again…

Woody LaBounty: It also gave people who never would have dreamed, I think, of owning a home a chance to get into that American dream. So you get the earthquake cottage, you’re a refugee who has nothing, and now suddenly you buy a lot for 100 bucks in the sand dunes of the Richmond, you have pretty much a free house.

Katrina Schwartz: Bernal Heights is another place with many earthquake cottages…people just moved their shacks from Precita Park to open land up the hill.

And some of them are still there…like the house we toured at the beginning of this episode.

Woody LaBounty: The one sort of key touchstone that you can tell about a cottage is the roof line. It has a very shallow pitched roof, kind of like a pup tent, like a Boy Scout tent. And then that is like your first hint because a lot of small buildings you’ll see have very steep pitched or flat roofs.

Katrina Schwartz: Woody says many shack owners quickly made improvements to their new homes — painting, building fences, adding additional rooms.

Woody LaBounty: There was sort of a stigma of having an earthquake cottage for a few years because it sort of signified you were a refugee, you needed help, you were poor. So people often, they quickly tried to hide sort of the pedigree of their houses and cover them with shingles quickly.

Katrina Schwartz: They wanted to hide that telling park bench green color. Most existing earthquake cottages are surrounded by modern additions. Or sometimes they’re a couple shacks placed together. That’s one reason it’s really hard to know how many still exist in San Francisco, they’re hidden. But Woody estimates between 30 and 50 earthquake cottages are dotted across the city.

Jane Cryan: The cottage in the front is made up of three and a half shacks, and then there’s a free-standing mid-size shack in the backyard.

Katrina Schwartz: This is Jane Cryan. She rented one of these preserved earthquake shacks in the outer Sunset in the 1980s. Jane is best known as a “shacktivist”…fighting to preserve earthquake cottages from development. But if it weren’t for the Beat movement in the 1950s, she never would have moved here in the first place.

Jane Cryan: The only reason I ended up in San Francisco is that Jack Kerouac, with whom I had correspondence from the time I was 16 years old told me that Milwaukee was no place for a poet. You should be in San Francisco.

Katrina Schwartz: By day she was an executive assistant, but writing and jazz piano were her passions.

Jane Cryan: And I moved in and I played piano for about six weeks, day and night, and an elderly gentleman from across the street came over and shook his finger at me and he said, young lady, do you know that you’re living in a couple of relief houses pasted together?

Katrina Schwartz: Her three room cottage was actually three earthquake shacks pasted together. This was 1982 and Jane had lived in San Francisco almost 20 years. But she’d never even heard of the 1906 earthquake and fire. Her neighbor’s passing comment sparked her curiosity. She spent nights and weekends obsessively going through old newspaper archives to learn as much as she could about the disaster and the earthquake cottages.

Meanwhile, her landlord made it known that he planned to sell her cottage…or worse demolish it and sell the lot.

Jane Cryan: Take down our history. So I had to do something.

Katrina Schwartz: Preserving these cottages — tangible pieces of such important history — became her life’s work. She took inspiration from one of the 1906 earthquake refugees she learned about in her research, a woman named Mary Kelly. Mary was an agitator, constantly questioning how the relief corporation dolled out aid and whether it was fair. She was such a pain to them they eventually evicted her from her cottage. But she refused to leave, famously saying:

Voice over portraying Mary Kelly: They can’t bluff me. I’ll stay with the house if they take it to the end of the earth.

Katrina Schwartz: She rode in her cottage as men hauled it onto a wagon and trucked it away. She stayed inside as they dismantled the cottage board by board. Jane finds Mary’s tenacity — and willingness to stand up to power — endearing.

Jane Cryan: She was exactly the way I was. If I saw something, I said something. And if I saw something that was not right, I said something louder.

Katrina Schwartz: Jane started a nonprofit called The Society for the Preservation and Appreciation of San Francisco Refugee Shacks. She fought hard to get the planning commission to designate her little shack a historic landmark.

And she was successful!

Jane Cryan: Landmark number 171.

Katrina Schwartz: But it was a bittersweet victory. The commission also said that Jane had to vacate the cottage in order to compensate the landlord for putting restrictions on his property. Jane bounced around from place to place after that, eventually moving back to Wisconsin, where she’s originally from.

Katrina in the tape: What do you miss most about San Francisco?

Jane Cryan: Oh, everything! Oh my god, San Francisco is the queen of the Golden West, for heaven’s sake!

Music

Katrina Schwartz: Historian Woody LaBounty says there are probably more earthquake cottages than we know. They’re hiding in people’s backyards, incorporated into bigger houses or used as sheds.

Woody LaBounty: They’re the last sort of most visible, tangible sign of one of the biggest things that ever happened to the city of San Francisco.

Katrina Schwartz: Increasingly these little cottages are being bought and torn down to make room for larger homes. But the ones that remain are a reminder of a refugee relief program that not only got people back on their feet, but made them homeowners. An example of San Franciscans coming together to repair and resurrect a beloved city.

Olivia Allen-Price: That was Bay Curious editor and producer Katrina Schwartz. Special thanks this week to California Revealed, an online database of oral histories and other archival materials. They helped us find Kathleen Norris’ oral history.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. Right now your membership means more than ever, give at KQED.org/donate.

Our show is produced by Gabriela Glueck, Christopher Beale, Katrina Schwartz and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

Extra support from Maha Sanad, Katie Sprenger, Jen Chien, Ethan Toven-Lindsey and everyone on team KQED.

Have a wonderful week.