Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: Hello, hello! I’m Olivia Allen-Price, back in the Bay Curious host’s seat after a 6 month maternity leave. For those who know me – pfew! I have missed this job, and you. And if you’ve started listening while I was gone – welcome! I’m so glad you’re here. Listen at the end for more update on me, but for now on the with show…

Something that I learned recently is every time you cross the Bay Bridge, you’re passing over one of the Bay Area’s most historic houses. We’re talking so close… that if you got out of your car on the bridge – not recommended – you could toss a rock and hit the home’s roof, a few hundred feet below.

Ben Kaiser: Even today, the mansion is stunning, even in its slow demise.

Olivia Allen-Price: That’s Ben Kaiser, this week’s question asker. The house he’s talking about is an odd sight to say the least: a once glorious mansion, tucked right beneath the Bay bridge’s eastern span.

There are a handful of grand old white houses grouped together in a little neighborhood of sorts. They’re multi-story with white columns framing stately front porches…. windows adorned with delicate lattice work. And the location could be primo… perched on the sloping green hillside of Yerba Buena island….looking out at the East Bay hills.

It’s an impressive scene… although there’s one house that stands out from the rest.

Ben Kaiser: It was called Nimitz house. It was called quarters one. It was, it was built in 1900 and played a certain role, I guess, in the naval efforts of World War Two.

Olivia Allen-Price: While none of these homes are small, this ‘Quarters One’ is notably more imposing than the rest. It’s a stately mansion – complete with multiple bedrooms and baths – and it’s a vestige from the Island’s military past.

These days though, the house tells a different story — one of peeling plaster, water damage, disrepair.

And since 2013, there’s been a new visual addition to the background: the rebuilt eastern span of the Bay Bridge.

Ben Kaiser: It’s this contrast in old with the house, and new with the bridge, and big with the house, but massive with the bridge.

Olivia Allen-Price: It’s a contrast indicative of an fascinating/captivating/intriguing history, one that Ben wants to know nearly everything about.

Ben Kaiser: I want to know its role in the Navy before it was renamed Nimitz house. I want to know about life after Nimitz passed away. But more than anything, I want to know what the future of it is.

Olivia Allen-Price: This week on Bay Curious we’re stepping inside the Nimitz house. (Yes, the same Nimitz with a freeway named after him.)

We’ll learn more about the house’s namesake and meet a retired Navy officer who used to live there. Then we’ll turn to the bridge.

Sponsor Break

Olivia Allen-Price: For much of the 20th century, Yerba Buena Island was part of the Navy’s West Coast operations. Quarters one – later known as the Nimitz house – was the official residence for the top/commanding officer on base.

Over the years, many Naval officers have called the house home. To start our story, Bay Curious reporter Gabriela Glueck met up with one of them – someone who can’t quite let go of the history.

Gabriela Glueck: Chances are, someone else lived in your house before you did.

If you look closely, maybe you can see traces of them.

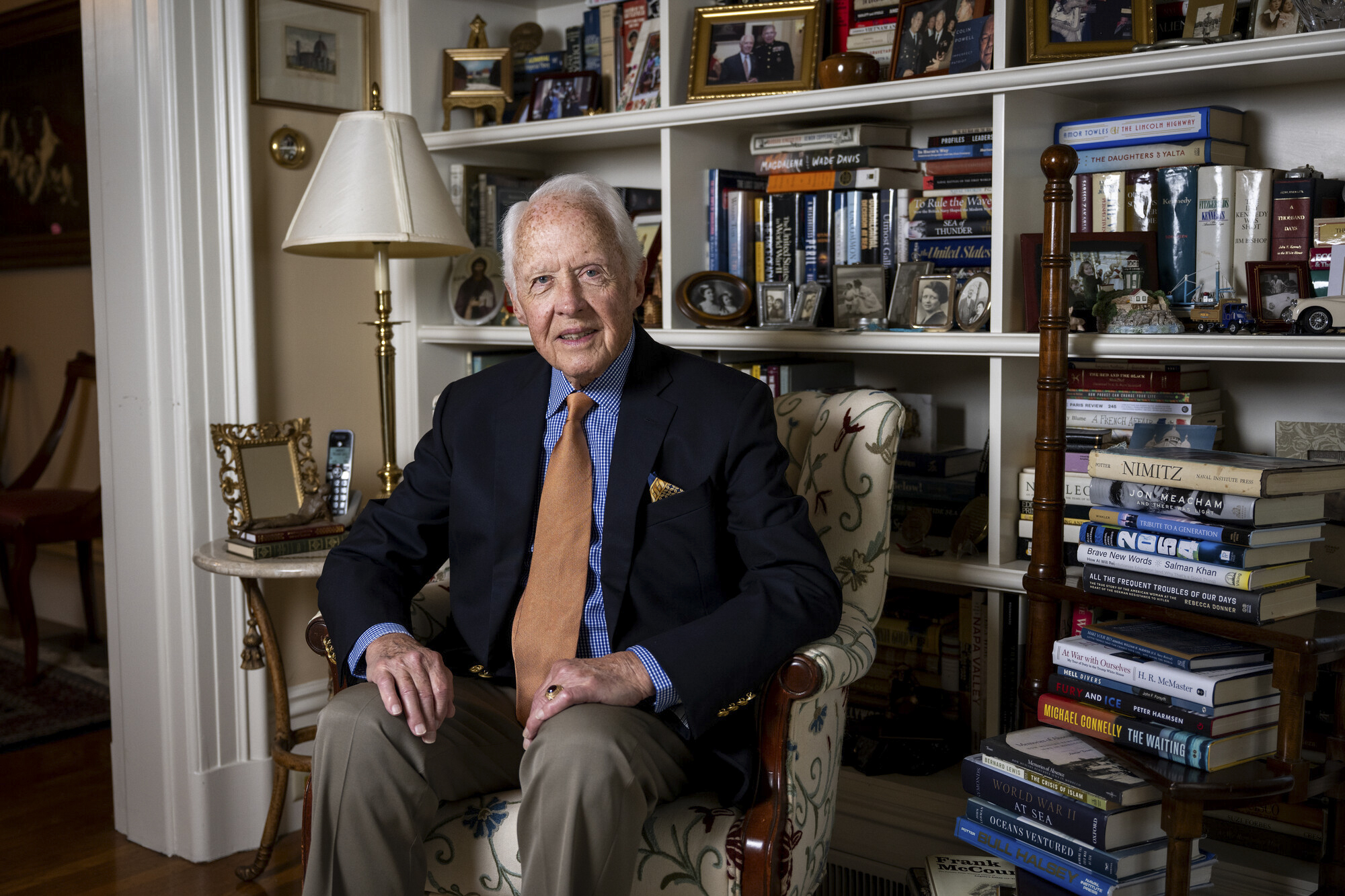

When it comes to the Nimitz house, RADM John Bitoff has spent a lot of time thinking about the man who came before him: Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

John Bitoff: I would find myself sitting there and thinking I wonder what happened here.

Gabriela Glueck: Nimitz was a legendary WWII Naval Commander and John’s childhood hero.

Archival war tape: The Nimitz story is not simply an account of an outstanding Naval officer who rose to a position of greatness and honour. It is also the chronicle of our modern Navy, its coming of age and its greatest triumphs in the epic struggle of the Pacific during World War II.

Gabriela Glueck: As a kid growing up in Brooklyn at the onset of the War, John watched this ‘epic struggle’ play out in real time. When the Japanese attacked Pearl harbor, drawing the United States into war, John saw the uptick of ships going in and out of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Archival war tape: The flames had hardly died before Chester Nimitz was called from a desk in Washington to take command of the Pacific Fleet. It was a dark time and a formidable task. It would take a man of vast experience and vigour to get victory out of wreckage and chaos. It would take a Nimitz.

Gabriela Glueck: With the United States officially at war, many Americans turned their focus to Europe. But John was preoccupied with the Pacific front and the Naval commander at its center.

John Bitoff: Well, my father was a big newspaper junkie and so there were always these front page photographs of the war in the Pacific and the pictures of Admiral Nimitz and Admiral Spruance. I just ate that up.

Gabriela Glueck: It’s hard to say how exactly we settle on a childhood hero — a mix of context, timing, and awe. But for John it was Nimitz.

In 1945, Japan’s formal surrender was signed in Tokyo Bay, the end of World War II.

By then Nimitz was a Fleet Admiral, holding the Navy’s highest rank. After the war, he became Chief of Naval operations.

Then, in 1947, he retired.

John Bitoff: And so when he retired, they decided to buy a house in Berkeley.

Gabriela Glueck: Nimitz had taught Naval Sciences there, before the war, and he’d also helped start the school’s ROTC unit. He wanted to spend his golden years there.

But when it comes to five star admirals, as John puts it, you never really retire from the Navy. So when Nimitz’s health started to deteriorate in his late 70s, the Navy stepped in.

John Bitoff: So we can provide you with a staff, a driver and a house staff, but you must live in public quarters. We cannot do that in a private home. They said, “You can have any set of quarters the Navy has.’ And Nimitz said, “Well, How about quarters one on Yerba Buena? And so they moved him over there.

Gabriela Glueck: Yerba Buena Island had been an important part of the Navy’s West Coast operations since the early 1900s. And during WWII, it fell under the jurisdiction of the Treasure Island Naval Station, serving as headquarters for the 12th Naval District.

Quarters one – where Nimitz was headed – was a fitting home for a legendary admiral.

John Bitoff: That’s how he became the occupant of that grand home and lived out his last days.

Gabriela Glueck: When Nimitz passed away in 1966 — four days before his 81st birthday — he was laid to rest at the Golden Gate National Cemetery. If you’d looked to the sky at the end of that service, you’d have seen a 70 plane flyover and heard the military bugle song of Taps floating through the crisp winter air

Sounds of Taps playing

Gabriela Glueck: It’s no surprise then, that the home he died in took on his name.

Ok, fast forward about 20 years. It’s 1989 now. Many a naval officer have come and gone from the Nimitz house and a new Rear Admiral is about to move in.

His name? John Bitoff. No longer a boy from Brooklyn but a Navy man in his own right, at the end of a long career.

As part of his final duty station, *John was assigned to the Nimitz house.

John Bitoff: And so I was absolutely astonished. It seemed like it was deemed to be. That I would find myself living in those very in those very quarters.

Gabriela Glueck: For John, it was a marvelous place to live.

John Bitoff: It had a grand porch leading up to the quarters, and it looked out onto a garden, a rose garden in the back that a double door let out, and steps led out to where they held receptions, there was a goldfish pond there. It was just absolutely gorgeous.

Gabriela Glueck: With Nimitz history surrounding him, John thought he’d take the opportunity to learn more about the Fleet Admiral. To kick off a sort of oral history project.

John Bitoff: I had heard that he used to go down to the firehouse on Yerba Buena Island and have a cup of coffee with the firemen, firefighters and and then at Christmas time, he was known to bring down chocolate chip cookies they cooked and he would share with the firefighters. And so I found out that the last remaining firefighter was retiring in a very short period of time. So I met with him.

Gabriela Glueck: And John and his wife also made efforts to restore the home to the way it was in the Nimitz days to honor the Fleet Admiral’s legacy.

They refurbished Nimitz’s desk and — using a photograph as reference — put it back in the library.

John Bitoff: In the very same spot where Nimitz had it, where he could look out the window

Gabriela Glueck: When John retired in 1991, he moved out of the Nimitz house.

John Bitoff: I was replaced by two other admirals. And then the whole Navy establishment was was part of the Base Realignment, and it was closed. All Navy activities were closed.

Gabriela Glueck: With the Cold War winding down, the US was looking to tighten its defense budget. And the base closure process — which ramped up in the 90s — was a big part of that effort.

These series of cuts hit California hard. More than 30 major bases shut down.

For John, the Treasure Island closure in 1997 was particularly worrisome.

John Bitoff: I knew that when the military closes down its bases, it’s not very good about maintaining historical edifices, and they basically don’t, don’t, they don’t have the wherewithal to do it.

Gabriela Glueck: While John’s wife managed to get the residence listed as a *historic site… most of the former base was ultimately turned over to the city of San Francisco.

John Bitoff: I was very concerned, because I love that House, and it is such a historic residence. If the walls could speak, they’d be a history lesson.

Gabriela Glueck: And soon enough, a new agency was created to oversee the base’s reuse and development. It’s called the Treasure Island Development Authority or TIDA.

Peter Summerville has worked at TIDA for over 20 years and says if he’s got the time, he’ll sometimes take his lunch break on the front porch of the Nimitz house.

Although – he admits – these days with the bridge there, it’s kind of loud.

Sounds of loud traffic

Gabriela Glueck: I met up with him at the house to take a tour.

Standing on the front porch, the first thing you notice about the place – after the bridge noise – is the many signs of weathering on the old home.

Peter Summerville: I think it’s a very challenging site. Exposure wise, definitely, we see that a lot, which is all our public infrastructure, that out here, we’re right in the middle of the bay, and it takes a beating.

Gabriela Glueck: The old porch ceiling fan is warped, the wooden blades drooping now.

Gabriela Glueck (in scene): Should we go inside?

Peter Summerville: Go inside? And I’m proud of myself. They actually brought the keys. One of my tricks I’m good at is getting places and forgetting my keys.

Gabriela Glueck: The slamming sounds you’re hearing now are from the door. After years of little use it’s jammed and Peter has to use all his body weight to open it.

Sounds of kicking at a door

Peter Summerville: It’s coming. It’s coming. I just don’t have anything to kick them. Oh, my goodness.

Traffic sounds fade away

Gabriela Glueck: When you get inside, the air feels… still… save for a few floating spider webs.

Kiah: We have beautiful hardwood floors, and then big, kind of big open spaces, big doorways, tall ceilings that really you can hear the echo of it.

Gabriela Glueck: That’s Kiah McCarley, she works with Peter. Compared to him, she’s new to the agency and it’s her first time in the house too.

And it’s a sight to behold.

Gabriela Glueck: What has happened on the ceiling?

Kiah McCarley: Yeah, it looks like we’re having some the paint or plaster come off the ceiling. A little bit of time damage, maybe a little bit of water damage.

Gabriela Glueck: There are speckles of black mold creeping up some of the walls, but other rooms look to be in pretty good shape.

After everything John’s told me about the house, I have to admit it’s a little bit shocking to see. And when I ask Peter about the city of San Francisco’s plans for the space, he gives me a kind of open-ended answer.

Peter Summerville: The long term plans for the house and for its kind of overall district are still being developed. They’ll ultimately be some sort of that kind of public use, either a collective reuse of the whole district, as, you know, a series of restaurants and bed and breakfasts, or an artists colony, or, you know, a variety of different things, or maybe their individual uses in each of the buildings.

Gabriela Glueck: Or maybe, he says, they’ll let an educational institution come in and use some leftover military houses for studios or classrooms.

But right now, they’re focused on basic repairs. Although Peter says the home’s historic designation complicates things.

Peter Summerville: All the improvements that you have to make in their systems, architecturally, all of that has to be done very sensitively, and is limited in terms of how much you can adjust the building as well. So even bringing the buildings up to kind of modern standards for practical reuse going forward is a challenge.

Gabriela Glueck: Heading into the main room, I notice pieces of broken glass all over the floor.

Turn the corner, and a beautiful, airy, sun room.

Head across the hallway and you’ll see an antique looking elevator next to the staircase.

Peter Summerville: Yeah, this is definitely some can do. Can do Navy engineering.

Gabriela Glueck: It’s a house full of contrast. Outside, the same is true.

Gabriela Glueck (in scene): It’s kind of funny right now, out the window, you can see, what would you call that? Like, the legs of the bridge.

Peter Summerville: This window is really just like a portrait of the bridge.

Gabriela Glueck: Back when John lived here, the window was mostly a portrait of the Bay. The Bay Bridge existed, true, but it used to touch down on another point of the island.

So, what happened?

Archival tape: On Tuesday, October 17 1989 at 17:04 Pacific Daylight Time, a strong motion earthquake emanated from a location south southeast of San Francisco, near Loma Prieta in the Santa Cruz mountain range.

Gabriela Glueck:The 6.9 magnitude quake was the strongest shock to hit the area since the 1906 earthquake

63 people were killed, and thousands more injured.

Sounds of emergency response radio and crackling

Drivers on the Bay Bridge watched as a section of the upper deck collapsed, falling onto the lower deck, trapping many and ultimately killing one motorist.

Peter Summerville: After that, as the years went on Caltrans, which owns the bridge. Caltrans and the state toll bridge authority determined that the Eastern span of the Bay Bridge needed to be replaced.

Gabriela Glueck: There were plenty of opinions about what the new span should look like.

The Oakland Tribune commented:

Voice Over reading newspaper clipping: Let’s make this a splendid front door to the East Bay….the bridges spanning San Francisco Bay are a world-class attraction that have made our Bay Area a living postcard. Let’s keep them picture perfect.

Gabriela Glueck: But one of the fiercest debates wasn’t about design at all. It was about location. Thousands of commuters were still using the old bridge, while the new one was being built. So the question was, where should the new bridge connect to Yerba Buena Island? Should it land south of the old bridge, or north of it?

The question became known as the alignment debate.

Nearly everyone felt they had something at stake. The Coast Guard, the East Bay MUD, the Port of Oakland, the Navy, the City of San Francisco, just to name a few.

Peter Summerville: So the city, and I believe, particularly the mayor’s office at the time, put up a strenuous defense of, you know, the southern alignment.

Gabriela Glueck: That’s the one that would have steered clear of the Nimitz house.

Peter Summerville: The city saw this district as sort of a great opportunity for reuse of these historic properties and to sort of bring them back to their, you know, original shine.

Gabriela Glueck: A handful of state lawmakers and the Navy agreed. But despite those objections the northern alignment won out. Competing interests from other agencies plus Caltrans own arguments over earthquake safety sealed the deal. Even the grand promise of the Nimitz house couldn’t tip the scales.

Peter Summerville: And that’s sort of the alignment that we have today. The new bridge is up. You know, it just sort of is what it is in our world.

Gabriela Glueck: The bridge construction project dragged on for decades. And by the time the new eastern span opened in 2013, it cost billions more than the original estimate.

For the Nimitz house, the Bridge’s impact was just as dramatic.

John Bitoff: Much of the ambience, and certainly destroyed the gardens and the buildings surrounding it.

Gabriela Glueck: What was once a stately home with sweeping views now sits in the shadow of concrete columns surrounded by the constant drone of traffic.

John Bitoff: I really don’t like going over there because the area is so changed. I was very saddened by it, and I didn’t want to go back again. The last time I went down to the quarters the house was in a terrible state of disrepair, and I made up my mind I didn’t want to go back there again, because it was ruining my memory.

Gabriela Glueck: For John, visiting the house now stirs up this very particular kind of feeling. It’s like driving by your childhood home — a place that’s meant so much to you — except it’s not yours anymore. The porch is different, the tree out front is gone, the lawn is overgrown. It’s your old house but not really.

John Bitoff: That’s precisely how I felt. You know, they say you can never go home, that’s the old saying, you can never go home. Well, that’s true in this case.

Gabriela Glueck: One thing is for sure, if the once grand Nimitz house is ever going to have a new future as an artist colony, a history museum, or anything else.

Sounds of traffic on the bridge

Gabriela Glueck: Soundproofing is going to be a must.

Car horn squeals

Olivia Allen-Price: That was reporter and producer Gabriela Glueck. Who, I want to give a special shout out to. Gabi filled in as producer on Bay Curious for the six months while I was out and did an incredible job. The team will miss her creativity, impeccable taste in music and infectious passion about whatever story she was working on. Luckily, she’ll continue to report for Bay Curious, so stay tuned for more from Gabi.

I also gotta give some flowers to Katrina Schwartz, who has been editing and hosting these past six months. It is truly a gift to be able to walk away from something you love as much as I love this show and know that it’s in the very best hands. Thank you Katrina – and I’m so happy to be working alongside you – and audio engineer extraordinaire, Christopher Beale – every day again.

Baby sounds…

Let me introduce you all to Clark, who was born in May. We call him our smiley guy because he cannot help but smile at you whenever you make eye contact. It was so special to get to spend these early months of his life with him, day in and day out. It’s a time of my life I know I’ll remember forever.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. If you’re not a member, join us! Whether with a one-time donation or a monthly membership – it all helps. KQED.org/donate is the place to go.

Our show is produced by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale, Gabriela Glueck and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

Extra Support from Maha Sanad, Katie Sprenger, Jen Chien,Ethan Toven-Lindsey and everyone on team KQED.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price. See ya next week!