Episode Transcript:

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Olivia Allen-Price: Hey everyone. This is Olivia Allen-Price. And last week on Bay Curious, we heard all about how the Bay Area went from military powerhouse to being left with dozens of vacant facilities. All to answer this question from listener Cameron Tobey…

Cameron Tobey: Why are there so many abandoned military bases around the Bay Area? And what’s the future plans for these bases?

Olivia Allen-Price: If you didn’t hear the episode, go give it a listen. It gets into the rise and fall of the military presence here. Today, we’re focusing on the future — what’s next for these spaces? Cameron is especially interested in if they can be used for housing.

Cameron Toby: You have a lot of abandoned homes in these. Do they plan on redeveloping those homes? Cuz we’re in desperate need of housing here in the Bay Area.

Olivia Allen-Price: Today we’ll see how some old military sites are being repurposed, redeveloped, razed and re-envisioned. Sometimes in really creative ways.

Pauline Bartolone speaking on site during a musical performance at Mare Island: Here we go, we’re going to walk inside this warehouse where the performance is going to be…

Sound of cello music reverberating in an old military building made of metal

Olivia Allen-Price: We’re also going to delve into why decades after the armed forces left, many of these spaces are still stuck in the long process of reinventing themselves.

Kent Fortner: I don’t think anybody has a playbook for this. I mean, converting these naval bases is so complex…

Olivia Allen-Price: That’s all ahead on Bay Curious. Just after the break.

Sponsor Message Break

Olivia Allen-Price: Here to help us look at what is happening at the decommissioned military sites around the Bay Area is Pauline Bartolone. Welcome, Pauline!

Pauline Bartolone: Hey Olivia. Great to be here!

Olivia Allen-Price: So, before we dive in, let’s acknowledge that there are dozens of former military sites around the Bay Area, and they all have their own story in terms of being redeveloped. So we’re going to talk about a few of them specifically, and then also broader trends.

Pauline Bartolone: Right! Some of these military sites are relatively small, like a swath of World War II barracks, and others are huge Navy bases covering several square miles. Chances are you’ve probably set foot on one without even realizing it.

Many people know the Presidio, and Fort Mason in San Francisco, which is now a mix of commercial, open space, and homes. There are other popular places like the Bay Area Discovery Museum in Sausalito, which is on a former army site. But then places mostly closed off to the public, like Point Molate in Richmond, which looks like it’s been collecting dust for decades.

Olivia Allen-Price: So some of these sites have been successfully redeveloped?

Pauline Bartolone: Yeah. Another would be Treasure Island. It was once Navy stomping grounds and now has a lot of apartments, with more on the way. Way more. But a lot of the spots I learned about were very much in some stage of transition. Especially the former big Navy bases, like Mare Island in Vallejo.

You heard a lot about the Mare Island Naval Shipyard on the last episode. It opened more than 150 years ago, just after the Gold Rush, and was one of the most active Navy yards in the world during World War II. But 30 years ago, the Navy stopped maintaining ships and submarines there.

The contamination from the Navy has mostly been cleaned up, but it hasn’t really taken shape as a new viable, residential community. The whole swath of land, which by the way is actually a peninsula … long story … is about 5000 acres.

Ambiance from the base fades up

Right now, there are just a few hundred homes there, a handful of retail businesses and a pretty active industrial sector. Anyone who takes a tour of it — which I did, it’s open to the public — will see it’s an eclectic mix of revitalization, and decay. But it has an intriguing charm. It’s a vast post-industrial landscape with beautifully restored historic buildings, right next to abandoned lots and warehouses.

Kent Fortner: It’s been this sort of hidden thing for a long, long time.

Pauline Bartolone: Kent Fortner is a perfect person to show me around. He’s a resident, and a business owner here. He converted an old Navy coal shed and turned it into the Mare Island Brewing Company. When he’s not brewing beer, he’s researching the area’s history through the local historic association.

Kent Fortner: if you have any desire to know naval history from particularly World War I and World War II, this place makes your hair stand on end…

Sound of car door slamming

Kent Fortner: So we’ll drive through the old officers road down here…

Pauline Bartolone: The residential neighborhoods are mostly tucked away in a couple of clusters. So you can drive for a block or two and see nothing but pavement on each side, then, a randomly placed palm tree. Actually, the trees here are a sight to see. Apparently the Navy collected saplings from all over the world.

Kent Fortner: Arborists from all over come to look at all of this.

Pauline Bartolone: There are more signs of Navy life all over the place. Kent pointed a lot of them out during our drive. Like cannons…

Kent Fortner: The cannons you see over here…

Pauline Bartolone: And giant metal anchors taller than most of us.

Kent Fortner: …Hidden in the bushes over here.

Pauline Bartolone: An ammunition bunker and a firing range…

Kent Fortner: There’s still bullet casings and potentially unexploded bullets in the soil. So that needs to be cleaned up.

Pauline Bartolone: Then, an old Navy hospital that specialized in lost limbs.

Kent Fortner: This is where you came to get your prosthetic fixed.

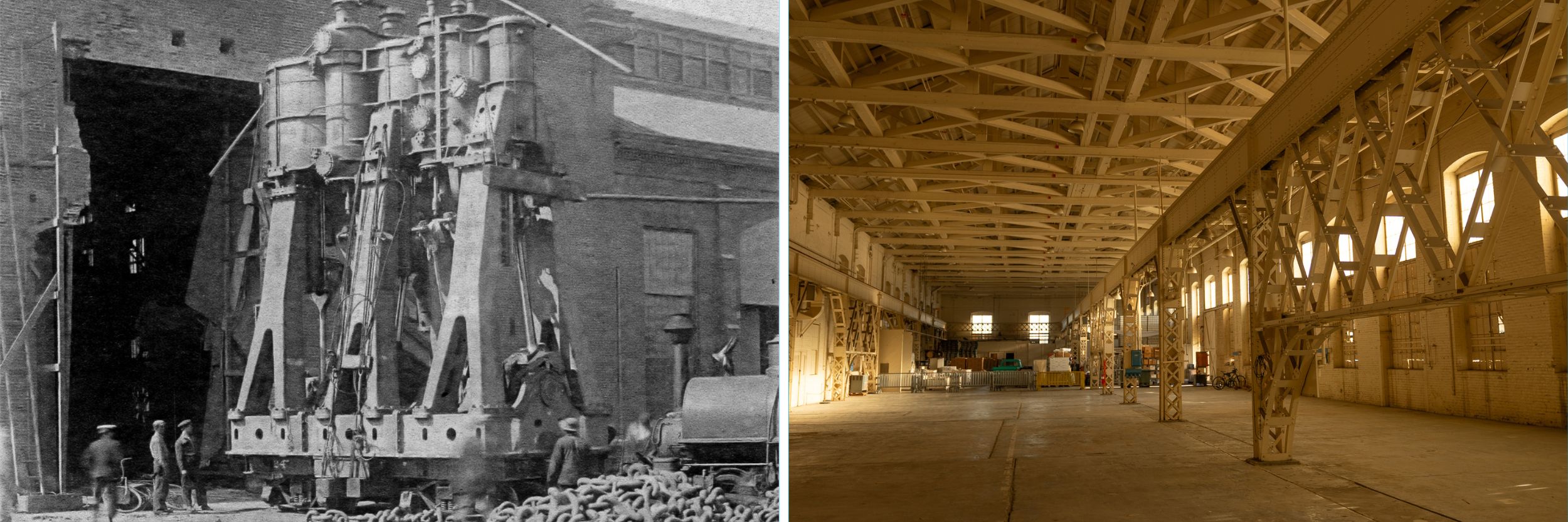

Pauline Bartolone: But the most glaring remnants of the Navy are the huge rusty metal cranes on the main historic wharf. There’s a row of them — towering several stories high, with massive empty concrete dry dock for the ships below.

Kent Fortner: Those are cranes that can lift incredible amounts of weight and that’s how they would assemble the ships back in the day … it’s mind boggling how large these ships were.

Pauline Bartolone: A number of Hollywood producers have been drawn in by the patchwork of landscapes here, using Mare Island as a backdrop for movies and TV shows.

Movie sound effect of robot transforming

Pauline Bartolone: Like Bumblebee, the transformer movie.

Clip from 13 Reasons Why: “Omg … What are you?”

And the more quiet teenage thriller, 13 Reasons Why on Netflix.

Clip from 13 Reasons Why: Voice 1 “I’m not going, not now, not ever.” Voice 2: “Why didn’t you say this to me when I was alive?”

Pauline Bartolone: But it’s not all military ruins. There are signs of rebirth too. Touro University bought the Navy hospital and holds classes there. Dozens of manufacturing-type businesses have set up here — high end furniture makers, modular home builders, and alcohol entrepreneurs, like Kent. But in terms of amenities for everyday living, like stores, modern parks and walkable neighborhoods … the former military base is not there.

Kent Fortner: I can’t say that it’s thriving right now. But we’re in this weird seam between when all the cleanup had to get done and when the new stuff is all going to start getting developed.

Music

Olivia Allen-Price: So Pauline … the Mare Island Navy Shipyard closed back in the mid 1990s. Other bases also closed decades ago. Why does it take so long to reinvent them?

Pauline Bartolone: Well I talked to regional planners, developers and city officials and heard some common things.

Number one is there is just a lot of environmental clean up to do on military sites. In Mare Island’s case, things like mercury, petroleum, underground fuel tanks, PCBs (those are chemicals in electrical equipment that were banned in the ’70s.) And this clean up takes a really long time. Like decades. Mare island’s not fully done with it.

Another process that takes a long time is public input to come up with a new plan for the site. In one case I heard, that took 7 years.

And a third factor is, it’s hard to keep private developers in the game. The developers are for-profit, and they assume a lot of risk and front-end costs in these massive projects. They take on basic infrastructure like sewer, water and electricity for these sites. They have to prove to their shareholders that the project will “pencil out” over a long period. One regional planner I talked to says the amount of investment private developers take on in these projects is pretty unique to the U.S. — he says in other countries the private sector wouldn’t be as involved at the infrastructure stage.

Olivia Allen-Price: That’s interesting. Can you tell me more about this problem keeping private developers engaged?

Pauline Bartolone: Yeah, the former Concord Naval Weapons Station is a perfect example of this. Their base closed in 2005, and they’re on their third private developer. The first developer left after labor disputes. The second developer was essentially booted by the city council. Now they have an ambitious plan for 12,000 housing units, a sports complex, even a college campus on the former site.

I talked to Guy Bjerke with the City of Concord about their drawn out process, and he says there are many regulatory steps they have to wait out.

Guy Bjerke: The need to get all of the resource permitting for wetlands and endangered species, and cultural sites right and the burial grounds. and those sorts of things. The need to work with the Navy to both monitor and facilitate how they’re cleaning up the sites so it can be turned into housing. So these are all complicated issues.

Pauline Bartolone: Bjerke says it’s probably going to be another 4–6 years before people see anything built above ground on the former Concord base. And again it closed 20 years ago.

Olivia Allen-Price: As for some of the other military sites … what are some of the plans for development there?

Pauline Bartolone: Well in general there’s a strong desire to create new housing on these sites, especially on the five major Navy bases like Mare Island, Alameda and Concord. Not only do these sites have a lot of acreage, but they’re also transit friendly, so they can help meet the area’s affordable housing and climate goals by keeping people where they work as opposed to commuting from Tracy.

There are examples of housing built on military sites. The former Hamilton Air Force Base in Novato, in Marin County, is just one example, and of course, Treasure Island.

Olivia Allen-Price: One note here — We’ve done some reporting on the redevelopment of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco’s Bayview, another massive project in the works. The base was declared one of the nation’s most contaminated sites in 1989. The city wants to put 10,000 homes on the land … but it’s been mired in a host of cleanup controversies. The Navy has spent decades cleaning there, but the work isn’t done. There are major concerns about contaminants they may have missed, and how sea-level rise could cause deeply buried toxins to resurface. Additional clean up is planned. There’s a lot to that story, more than we can get into right now, but we’ll link to some resources in our show notes.

Pauline, What can we learn from the sites that have been successfully redeveloped?

Pauline Bartolone: Well I’m told places like the Presidio and Fort Mason have really benefited from being on national park land. They’ve had one consistent owner with steady revenue — the federal government — which can see through a long term vision for the place. For the other spaces, one proposal I heard for speeding up the development is to essentially divide the projects up so a collection of groups can move things along at the same time.

Olivia Allen-Price: Sounds like reinventing these sites is very complicated and involves a lot of different players, but perhaps that’s not surprising.

Pauline Bartolone: Right … I do want to say that some people like the bases just how they are: raw, industrial, with lots of open space. History buffs for sure, and artists and makers. There’s plenty of space to create. In fact, a group of sound artists have been holding performances regularly at Mare Island for 10 years.

Sound of a crowd gathering in a big room. A voice says “Hello everybody”

Pauline Bartolone: They call the series Re:Sound … And it’s pretty experimental.

Music played with a cello

Pauline Bartolone: The day I went, a cellist named Lori Goldston from Seattle was playing … improvising of course.

Music played with a cello

Pauline Bartolone: She performed in an empty metal storage shed right on the historic dock. The giant rusty cranes were all around us. The Navy architecture was part of the show … the metal walls creaked with the breeze. The audience sat on the concrete floor, which was once covered with military supplies.

Distant birds with cello music

Pauline Bartolone: Many listened with their eyes closed, almost in a trance, taking in the string music and the birds in the distance.

Artists like Lori Goldston are among many people here who are working with the island’s rich history just as it is, while finding a new purpose for it at the same time.

Lori Goldston: It’s nice to see all this infrastructure being put to good use. I’ve seen a lot of empty space and wonder why there aren’t more things happening here.

Pauline Bartolone: We’ll see more built on these military bases. Probably housing. But it’s going to take a while.

Olivia Allen-Price: Pauline Bartolone, thank you!

Pauline Bartolone: My pleasure.

Olivia Allen-Price: Thanks to listener Cameron Tobey for asking the question that sparked this two-part story. And a special thanks to Matt Regan of the Bay Area Council and Mark Shorett of the Association of Bay Area Governments for their expertise.

Bay Curious is made in SF at member-supported KQED. Find out more about becoming a member, and supported the work of Bay Curious, at KQED.org/donate.

Bay Curious is made by Amanda Font, Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale, and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

Additional Support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan and everyone on Team KQED. Thanks for listening!