Episode Transcript

Katrina Schwartz: This is Bay Curious, the podcast that answers your questions about the San Francisco Bay Area. I’m Katrina Schwartz.

It’s hard to imagine life here in the Bay without the bridges that allow us to crisscross the water. Thousands of us do it every day. Sometimes it’s a real pain.

Newscaster: We have a real traffic mess on the Bay Bridge eastbound.

Newscaster: Thousands of drivers got home late tonight after a protest over vaccine mandates sparked a chaotic scene.

Newscaster: We continue to track major delays across the San Mateo Bridge; this has just been the headache of the morning.

Katrina Schwartz: But since we all spend so much time sitting in bridge traffic, we get lots of questions about things you’ve noticed from your car windows. Like:

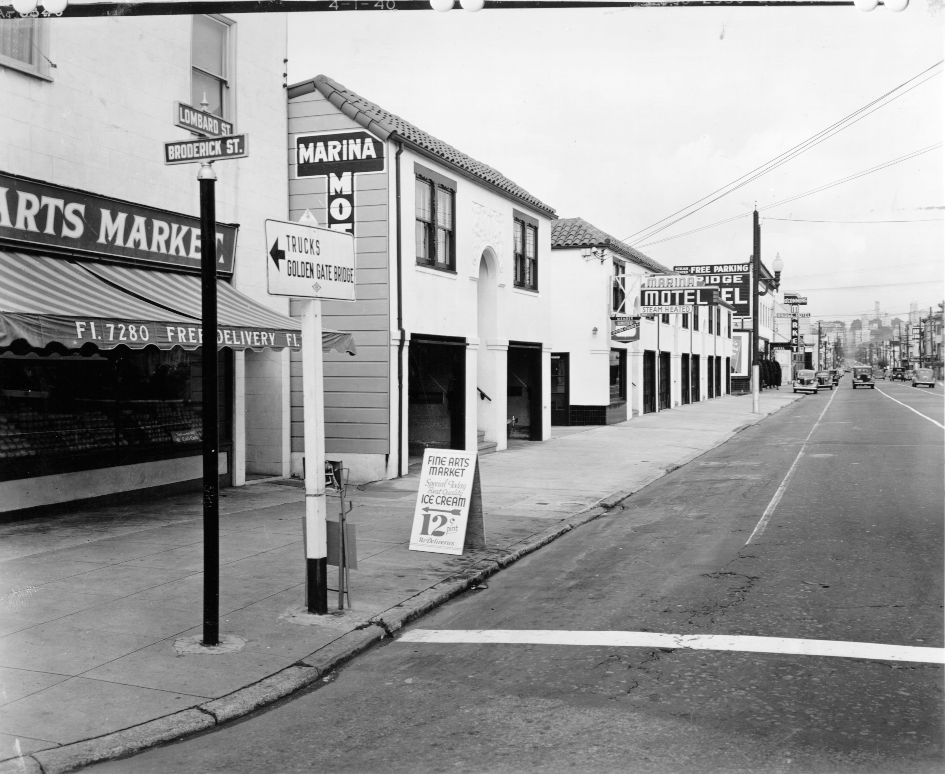

Jessica Kariisa: Why are there so many motels on Lombard Street as it approaches the Golden Gate Bridge?

Katrina Schwartz: And…

Gabriela Glueck: What was the original San Mateo-Hayward Bridge like?

Katrina Schwartz: Today on the show, it’s a bridge-focused lightning round where we answer several of your questions. First, we’re going to tackle why there are so many motels on Lombard Street, and then we’re moving south to a bridge that doesn’t always get the recognition it deserves. Stay with us.

Sponsor break

Katrina Schwartz: These days, Lombard Street is best known for the short section that wiggles down a steep hill, beautiful mansions on each side. Cars line up for the chance to drive it. But just down the way from there, Lombard becomes a main thoroughfare to the Golden Gate Bridge. And dotted along it are dozens of motels. Why so many in one place? Bay Curious reporter and sound engineer Christopher Beale went to find out.

Christopher Beale: I thought the most obvious place to start to answer this question was to take a look for myself, so my partner and I decided to take a little drive down Lombard Street and just count how many hotels we saw.

Christopher Beale: We’re gonna start at Franklin. I’m just curious how many we are going to get, there’s two and we haven’t even turned onto Lombard yet.

Christopher Beale: We drove west, towards the Golden Gate Bridge.

Christopher Beale: All right, so there’s the San Francisco Bay Inn, the La Casa Inn.

Montage of counting motels

Christopher Beale: OK, counting all of these might take a while.

Reagan Rockzsfforde: Well, you look on that side and I will look on this side.

Christopher Beale: We’ll check in on this later, let’s get to the other part of the question. Why are these motels, or motor lodges, here in the first place?

By the 1920s, Americans were falling in love with the automobile, and highways began to snake across the United States, connecting people from coast to coast like never before.

In the early ’30s, plans were in place to build what was, at the time, the longest suspension bridge in the world, right here in San Francisco.

The Golden Gate Bridge would stretch across a narrow, deep channel of water long known as The Golden Gate, soaring high above the water, and allowing automobile traffic from Marin County into San Francisco. Lombard Street was going to be the main approach road for this massive bridge.

Heidi Detjen: There wasn’t a lot of people who lived over there then, so it was not a very busy road.

Christopher Beale: That is Heidi Detjen. She is the owner of the first motor lodge to pop up on Lombard Street, it’s called the Marina Motel and Heidi’s grandfather started welcoming guests in 1939, just two years after the Golden Gate Bridge opened. Now, of course, her grandfather didn’t invent the concept of a motor lodge but…

Heidi Detjen: He came out of retirement to build this after visiting a motor courtyard, I wanna say maybe Niagara Falls or something.

Christopher Beale: A motor lodge, or a motel is a hotel that is specifically targeted at motorists, they usually offer direct access to the parking lot from the unit vs having to enter and exit through a more traditional hotel’s central lobby.

Heidi’s granddad believed that the Golden Gate Bridge would bring people in cars who needed a place to sleep, and that a motor lodge was just the thing to service those motorists. And boy was he right!

Once the bridge opened, Lombard Street got really busy, really fast! The Marina Motel was perfectly situated to take advantage of all that traffic along sleepy Lombard Street.

Heidi Detjen: When they built this place, it was just a two-lane road with a lot of multi-story shingled housing along it.

Christopher Beale: But right after the bridge opened, officials decided to expand Lombard Street.

Heidi Detjen: And they pushed it from a two-lane road into a six-lane road.

Christopher Beale: The south side of the street was bulldozed to make room for the new lanes of traffic. But the Marina Motel is on the north side of Lombard, closer to the Bay and the Palace of Fine Arts, so it wasn’t directly impacted until the road was finished, that is.

Heidi Detjen: That’s when all these other motels appeared.

Christopher Beale: It’s rare for land to be available at that scale in San Francisco, and before long, dozens of motor lodges of varying quality and price dotted the south side of Lombard Street, giving the Marina Motel some very real competition.

Heidi Detjen: In the old days, people literally got off the Golden Gate Bridge, and they went from motel to motel to motel to try to get the best rate. Unfortunately, then we were on the wrong side. So as people were coming over the Golden Gate Bridge into San Francisco, they would go all to the motels on the other side, and we stood empty.

Christopher Beale: The Marina Motel would go through ups and downs, but is still there today, and still in the family. Business has gotten easier thanks to the internet.

Heidi Detjen: Nowadays, people can look your pictures up online. So we get a clientele who really appreciates that and appreciates the historic significance.

Christopher Beale: So that covers how Lombard’s motor lodges got to be there in the first place, but just how many are we talking about here?

This is by no means an official count, but on our single road trip down Lombard that day, between Franklin and Chestnut streets, my partner and I counted…

Christopher Beale: 24, like old motor lodge style motels in just a mile or so. Yeah, I think that qualifies as a high concentration, don’t you?

Reagan Rockzsfforde: Mm-hmm.

Christopher Beale: Now, we’ve all heard the headlines about how hotels aren’t doing so well in a post-COVID era, but Heidi’s family has weathered ups and downs in the business before.

Christopher Beale: Why do this in 2025?

Heidi Detjen: Oh, this is the best business ever. People come here, they’re on vacation, they’re happy. I go home and I tell my family about it at the dinner table, like, oh, I met this scientist…

Christopher Beale: The traffic from the Golden Gate Bridge is why these hotels popped up in the first place, and though these motor lodges are sort of a relic of a bygone era, Heidi said these days business is still thriving, possibly because of that fact. Nostalgia is in, so is free parking.

Heidi Detjen: I feel like I’m kind of holding up the legacy. My family has owned it since the 1930s, and I’m the third generation doing it, and now my daughters are involved as well. There’s a lot of heart that goes into this place.

Katrina Schwartz: That was Bay Curious reporter and sound engineer Christopher Beale.

We just heard about the huge impact the Golden Gate Bridge had on the Marina neighborhood of San Francisco, now we’re going to turn to a bridge that doesn’t get nearly the same hype as its International Orange friend.

The San Mateo-Hayward Bridge. Today, it’s a fairly unassuming workhorse bridge. But did you know the original actually preceded the Golden Gate Bridge by almost a decade? It was once the longest bridge in North America. And one of the skinniest!

Kathleen McKusick of Redwood City used to work in biotech near Bridgeview Park in Foster City. Which is how she came to ask us this question:

Kathleen McKusick: I stumbled across a remnant of the 1929 San Mateo Bridge about a dozen years ago. I would love to know more about that original bridge in its heyday.

Katrina Schwartz: Built in 1929 and then called the San Francisco Bay Toll-Bridge, we sent KQED’s Rachael Myrow to check it out. This story first aired in 2023.

Rachael Myrow: If you’ve walked or cycled along the Bay Trail on the Peninsula, you know it passes under the San Mateo-Hayward Bridge.

Kathleen McKusick: My daughter and I were here on the weekend to ride bikes on the Bay Trail, and we went on the bikes a little farther than I usually went on foot, and here was this astonishing little piece of a bridge. Which raised all kinds of questions in my mind.

Rachael Myrow: Kathleen McKusick Googled it, naturally, as did I, and there just isn’t a whole lot out there. The best resource? One article written a few years ago for the Hayward Historical Society, an article written by this guy.

John Christian: John Christian, formerly an archivist at the Hayward Historical Society.

Rachael Myrow: We all met at the Bridgeview Park, where you can spy a little stub of the old bridge alongside the big new one. It’s a noisy park. You can hear the traffic from the new bridge, not to mention planes flying overhead from SFO.

John Christian: This is the first time I’ve been over here. I guess I’m too Hayward-centric. But yeah, I’ve never really seen it from this side, to be honest.

Rachael Myrow: According to Christian, the Hayward-San Mateo Bridge was originally proposed in 1922 by the Oakland Chamber of Commerce as a way to jump-start commerce between the Peninsula and the East Bay. Construction began in December of 1927. Flash forward to March 2, 1929, and we have…

Old-timey music

Rachael Myrow: The grand opening of what was then called the San Francisco Bay Toll-Bridge! Now, quick production note. 1929 is a tricky time for sound reporters in the Bay. Much of the news footage from that era was still silent.

Archival recording of Calvin Coolidge talking

Rachael Myrow: What talkies there were typically brought sound to big, national news stories. But the Bridge opening in 1929 was a big deal for the Bay Area.

Sound of Morse code being sent over a telegraph

Rachael Myrow: And then-President Calvin Coolidge participated in the dedication by pressing a telegraph button in Washington, D.C., that directed the unfurling of an American flag from the bridge.

Sound of a flag unfurling sound, crowd says “Ahhhh”

Rachael Myrow: Then-San Francisco Mayor James Rolph, who was known to love attending celebrations of almost any kind, was the biggest local celebrity to show up in person.

Sounds of 1929 Ford AA Truck engine starting up

Rachael Myrow: Not unlike the Golden Gate Bridge to the north, this bridge helped farmers get their goods to market. In the 1920s, the region on both sides of the Bay was rural, as opposed to suburban, as it is today. Farms, orchards, canneries, salt harvesting. And maybe because it wasn’t designed primarily for commuter traffic, I think it’s worth noting that the original bridge was only 30 feet wide with just two lanes, and about 7 miles long.

John Christian: Looking at the new bridge, I mean, compared to the old bridge, this bridge is a monster. You know, this is like, six lanes. The original bridge would have been just two lanes, back and forth.

Rachael Myrow (in the field): Petite, and also, I have to say, terrifying. Right? Two lanes, two lanes only, one going in one direction, one in the other. 30 feet wide, going over, over the Bay.

John Christian: Right.

Dramatic music swells

John Christian: Yeah, I mean, it must have, I guess, you know, probably it was kind of fun, I guess. But yeah, probably a little horrifying.

Rachael Myrow (in the field): Especially if there’s a stiff wind? Picking up off the water?

John Christian: Yeah, I mean…

Rachael Myrow (in the field): Driving a Model T Ford?

John Christian: Nobody was blown into the water, as far as I can tell.

Rachael Myrow: Fun fact: The original toll was 45 cents, about $8 in today’s money! So, Christian says, adjusted for inflation, it was more expensive to cross in 1929 than it is today! Takes the sting out of today’s $7 toll? Or maybe not.

Anyways, it wasn’t long before newspaper articles were calling the old bridge “antique.” By 1954, 7,400 cars and trucks were crossing every day. Because the rural towns on either side of the Bay did become suburbs.

John Christian: You know, it was a small bridge taking you to a small place, you know? And now it’s like, this massive, like, you know, city center to city center.

Rachael Myrow: And the biggest complaint about this bridge was not how slender it was, but the electric drawbridge that went up on average 6 times a day to let marine traffic pass underneath. That brought cars and trucks on the bridge to a standstill.

So in 1961, the groundwork was laid for the construction of a wider, taller bridge, to be built just a few feet north of the original span. The old bridge was dismantled, piece by piece, except for the small bit you can still see from Bridgeview Park today. According to the state’s Department of Transportation, by the way, the new bridge is still the longest bridge in California.

Rachael Myrow (in the field): So now that you know the full story, any thoughts?

Kathleen McKusick: I really wish that the pier were open and I could walk out onto the bridge. That would be a dream come true.

Katrina Schwartz: That story was reported by KQED’s Rachael Myrow.

Both of the questions in this episode won Bay Curious voting rounds. We’ve got a new set of questions up on our website right now, BayCurious.org. Head on over to cast your vote for what we should answer next. And be sure you follow Bay Curious so you never miss a new episode.

Our show is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. Bay Curious is made by Gabriela Glueck, Christopher Beale and me, Katrina Schwartz. With extra support from Maha Sanad, Katie Sprenger, Jen Chien, Ethan Toven-Lindsey and everyone on team KQED.

Have a great week!