Abené Clayton [00:01:47] So, in covering gun violence, people will ask me and ask police, ask officials, why are shootings happening? Why are homicides either up or down?

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:02:00] Abené Clayton is a reporter with the Guardian’s Guns and Lies in America project.

Abené Clayton [00:02:06] And in my mind, I would always think like, well, you’re not gonna have a real answer unless you ask the person who did it. When we talk about crime dynamics, there’s so much analysis and research and commentary that goes into it, but a major sort of missing piece in all of this is talking directly to someone who either did the specific thing or has done something similar, and we don’t do that very often, if at all.

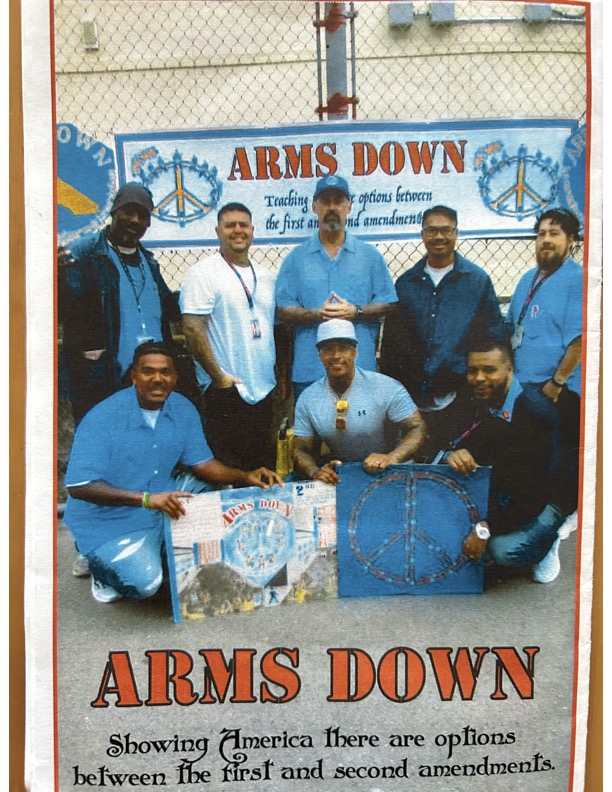

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:02:44] You reported on a sort of unique program that turns this on its head in a way because this sort of idea of gun violence prevention is actually happening inside of a prison. Tell us about Arms Down out of San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, formerly known as San Quentin State Prison.

Abené Clayton [00:03:08] So Arms Down is a mutual help group for firearm offenders styled after these sort of self-help rehabilitative programs that exist in prisons. Right now, they have about 120 guys who, one half of them meet on Tuesdays, another half meets on Fridays. And during those sessions, they sit in groups of like eight to 10, 12 guys pretty much share the experiences that led them to prison and to the Arms Down circles.

Automated Voice [00:03:43] To accept this call, say or dial 5 now.

Abené Clayton [00:03:48] It was founded by an incarcerated man named Jemaine Hunter, who is in prison for a 34 years to life sentence. He’s been inside for the last two decades or so.

Jemaine Hunter [00:04:02] Hi, my name is Jermaine Hunter. I am the founder of Arms Down, a group that’s mutual help for gun offenders.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:04:16] What is his story?

Abené Clayton [00:04:18] Jemaine is from Fresno. He was born and raised there in the 80s and 90s.

Jemaine Hunter [00:04:24] Fresno, California is like one of them cities back in the, especially back in the eighties, it was like, slow.

Abené Clayton [00:04:33] Kind of at the height of the crack, super predator epidemic that we look back on today as a reference point for so many things, whether it’s like tough on crime tactics, what we know today as like community violence, all sorts of things.

Jemaine Hunter [00:04:50] I was pretty much ambitious with the streets, getting out, trying to be my own man, you know, as a kid, wanting to get out and have things that I wasn’t provided in the household.

Abené Clayton [00:05:09] He told me that his first interaction with gun violence was actually a shooting that happened in his home between his grandparents when he was four or five. I think that kind of sets the stage in his mind for what guns were used for.

Jemaine Hunter [00:05:26] I was out there standing in the street selling drugs, doing whatever it was that us as hustlers and people that’s prone to the street life do. And the firearm was just an essential tool to carry on with that lifestyle.

Abené Clayton [00:05:49] And I think this mindset, he carried it with him, right? Until his offense at age 24, that ended in him being convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 34 years to life.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:06:04] When Jermaine was in prison, he sort of realized that he wanted to start this program Arms Down. Why did he want to start his program? What did he feel like was missing that he really wanted to fill?

Abené Clayton [00:06:22] He had been in a couple other facilities before getting to San Quentin. And all during that time, he was doing the self-help programs, you know what I’m saying, really trying to heal, you know, victims awareness, things, all of this stuff that people will recommend you become a part of if you are incarcerated. But he told me that there was no group that specifically addressed firearms.

Jemaine Hunter [00:06:49] Just talking to other people on the yard or in prison, you know, after doing seven, eight years or whatever their crimes, a lot of them still thought about having a firearm after doing all this time. So I definitely understood that it was a need for this.

Abené Clayton [00:07:07] In some of the places he was, firearms were seen as like a footnote, right? It was like, oh, you had all of these other things. You just happen to use a gun. But for him and so many other people in who are incarcerated, guns were like a central part of their lives.

Jemaine Hunter [00:07:23] All the classes was basically saying that we were having guns just to kill. I had a gun every day of my life. I just committed that crime that one day. So what happened to all those days that I was just packing a gun and not using it? So I felt like it was a need to talk about that.

Abené Clayton [00:07:51] It was hard for some folks to understand why, without a space that was specifically tailored to those conversations.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:08:01] So how does it work exactly, Abené? Like, what does it actually look like to go through this program?

Abené Clayton [00:08:09] In the earlier parts of the cohort, they start by discussing their first interactions with gun violence. For example, Jemaine may talk about the shooting incident with his grandparents when he was a kid.

Jemaine Hunter [00:08:24] We talk about growing up as kids, what it was that your beliefs were with firearms to try to combat a bunch of faulty beliefs and rumors that you may have heard as a kid.

Abené Clayton [00:08:41] They also talk about what they thought guns were for and how those perceptions were shaped by their past experiences and things they were exposed to, whether it’s through television, whether it was through their neighborhoods, et cetera, and they’re really able to dig in there. And they also do an exercise where they talk to somebody who stands in for their victim.

Jemaine Hunter [00:09:08] We talk about the primary, secondary, and tertiary victims, everything from the person that you hurt to the person who shoots a gun off around the school. How does it affect them kids that’s in the playground by just hearing them shot?

Abené Clayton [00:09:29] The arms down participant will have to sort of take accountability, talk about the situation that happened that led them to prison and to the group, and they go through that process as well. So it’s a multi-pronged approach to ultimately getting understanding about what led you to believe that a gun was your only tool in that moment.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:10:08] It almost sounds like an alcoholics anonymous group, but for folks who’ve used guns in some sort of crime.

Abené Clayton [00:10:27] Yeah, I mean, that’s exactly what it is. When I first started talking to Jemaine and Jesse Milo, one of the group’s co-creators, they compared it directly to like alcoholics anonymous, narcotics anonymous, right? Like anger management. They compared it to all of these different things, but specifically for people with what they’ve coined as a firearm addiction. They think about it in the same way. And when Jemaine would describe how he thought about direarms it was in line with that, right, you wake up, you’re like, where is it? How do I get it if I don’t have it? Where is it gonna come from?

Jemaine Hunter [00:11:06] Firearm addiction is basically you being codependent for a firearm. The chaos, the things that we’ve been through with a firearm, and you still feel like it’s a need or you’re codependant on this same tool, then you’ve got to address that there’s an issue with this firearm.

Abené Clayton [00:11:27] You go to prison for it, you lose relationships because of it, but still, you still need that thing. And while that’s a term I’d never heard before, once I heard it, I was like, well, that makes sense.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:11:39] Yeah, and I’ve never heard that phrase either, firearm addiction, until you mentioned it. And I guess I wonder why do you think gun violence prevention hasn’t always considered this as part of the solution? What does naming it as an addiction do?

Abené Clayton [00:12:01] I think that it allows for sort of updated and expanded ways of thinking about how to address it. It was just a level of insight that I was like, wow, this is missing from the discourse. You know what I’m saying? This is missing. From the conversations we have about gun violence all the time that already are mostly focused on like police prosecution and the like. To binaries of guns everywhere or guns for no one nowhere except for cops. In terms of like outside world violence prevention, I think that people prefer for the redemption arc to be done right before they start listening to someone. They want you to already have been out, been rehabilitated, working with kids, and then they’ll take your expertise on gun violence a little more seriously. You’ll be allowed to have this sort of platform. But also I think people may just like be like, oh, well, they’re in prison. What do they have to offer? Honestly, you’re in prison. What can you do to like affect the outside? But as we’re seeing through Arms Down, there’s actually plenty you can do, especially when working in concert with folks who are on the outside who believe in what all you got going on.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:13:19] It does sound like there is a sense that what is happening here with Arms Down is a successful model, but of course we are just talking about one program at one prison. And are there efforts happening to expand arms down into other prisons?

Abené Clayton [00:13:38] Yeah, there are. They’ve gotten interest from other guys in prisons throughout the state who are like, man, we want this program here. So there’s a lot of interest and plans to get the curriculum down and sort of copyrighted and protected before it gets sent out are underway as we speak.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra [00:14:00] So going back to the Arms Down program at San Quentin, I know that once the cohort finishes the program, there’s a graduation ceremony and you actually went to the most recent one. What was that like?