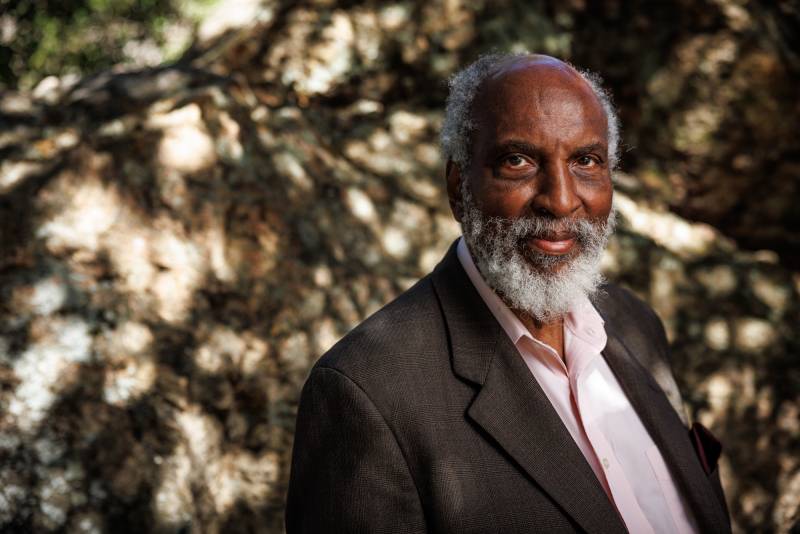

powell spoke with The California Report Magazine host Sasha Khokha as part of a series on Californians and resilience.

Below are excerpts from their conversation, edited for brevity and clarity. For the full interview, listen to the audio linked at the top of this story.

On what ‘bridging’ means:

A simple way of thinking about it is just that it brings people together. We’re willing to be present with someone, we’re willing to listen to someone, not because we think they’re right, not because we’re gonna change our mind or change their mind, but because they’re human.

We recognize, even in those apparent differences, we share something. So bridging is willingness to see each other, not to become each other, to see each other. It requires being present and being curious. And it requires listening with the heart, not with the mind.

The mind is always listening to be right and prove the other person wrong. Whereas the heart is listening to build relationships. It’s like, “Tell me about your fears. Tell me about your kids. Tell me about what’s important to you.”

On belonging and othering:

We oftentimes create our sense of coolness or belonging by dissing other people. If you want to be in this group, you’ve got to hate that group. And that’s one reason that the title of the first book was called Belonging Without Othering.

Because belonging with othering is a normal staple practice in many religions, and much of nation-building and race-building. “You are OK if you’re part of us, and those beings over there are not even people, they’re not even human.”

If you think about the United States, the Constitution starts off, “We the people.” But then for the next 250 years — and I would say even today — we’ve been fighting about who is that “we”?

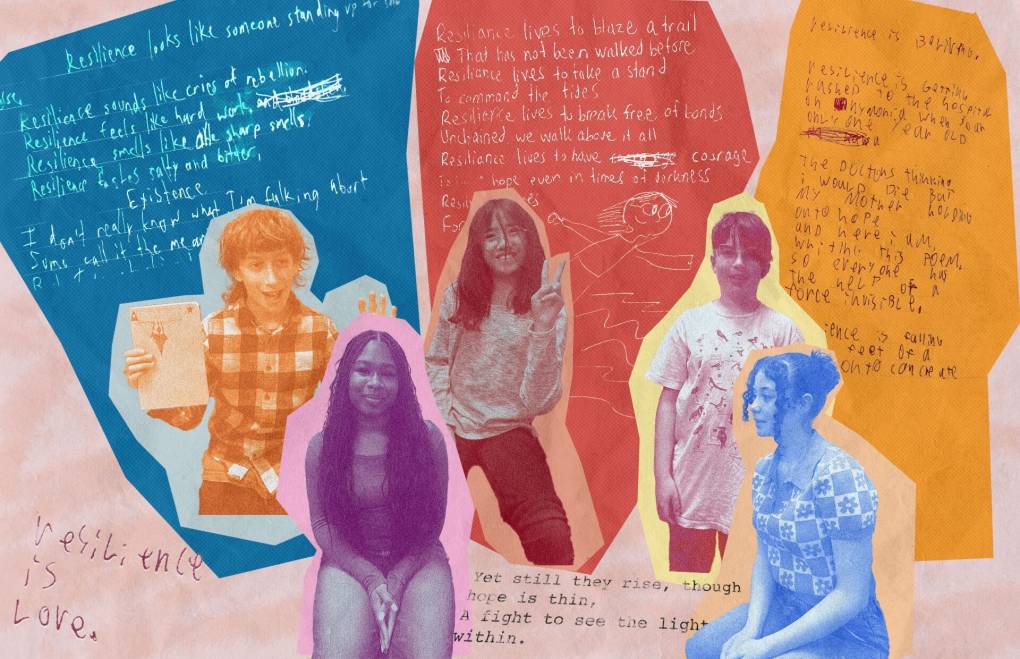

On the relationship between bridging and resilience:

Resilience is largely a team sport. So if you’re by yourself, isolated, it’s hard to be resilient. And part of being resilient… is being recognized. Bridging is where we recognize the humanity in each other.