Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Katrina Schwartz: Post World War II America was a time of economic opportunity and people wanted cars.

Advertisement: Mustang, the original, America’s favorite sports car. With three new models.

Katrina Schwartz: Imagine the open road, cruising with the windows down, radio blaring. The epitome of freedom. That’s the image Ford was selling.

Advertisement: Falcon 1966, low, lean, long hooded.

Katrina Schwartz: At the start of the 1960s Ford had cornered nearly a third of the U.S. car market. Many of those vehicles were manufactured in the Midwest, but Ford automobiles were so popular the company had expanded manufacturing nationwide. Ford had outposts in Edgewater, New Jersey, Seattle, Washington, Dallas, Texas, just to name a few.

Advertisement: You’re ahead in a Ford, all the way!

Katrina Schwartz: Many of these factories have since closed but some of this history is still hidden in plain sight. You might have even stepped foot in an old Ford factory without knowing it. Take the Great Mall of Milpitas in the San Francisco Bay Area, for instance.

Bob Marsden: This is Bob Marsden, reporting from the Ford Motor Company assembly plant at Milpitas.

Katrina Schwartz: That’s right. The Great Mall of Milpitas used to be an enormous Ford factory.

Bob Marsden: This particular facility which employees 3,000 is the West Coast plant for Mustang and light truck assemblage.

Katrina Schwartz: The plant first opened seventy years ago, on May 17th, 1955. At the time, it was one of the largest automotive assembly plants on the West Coast. It represented thousands of good jobs and brought social change to what had been a small, agricultural community. But visit the mall today and there isn’t much left to mark this history. Bay Curious listener Brandon Choy only knows about it because he saw a plaque once that mentioned the old Ford factory.

Brandon Choy: I was just wondering what the story behind this former Ford plant is and how it eventually became the Great Mall?

Katrina Schwartz: This week on Bay Curious, we dive into the history of the Ford factory that put Milpitas on the map. We’ll hear from former Ford workers about life at the factory and then we’ll explore how the plant changed Milpitas itself, transforming a quiet agricultural town into a bustling city, a city with one of the first integrated neighborhoods in America. I’m Katrina Schwartz. Stay with us.

Katrina Schwartz: The Ford factory opened in Milpitas in 1955. To help us understand its history and how it became the Great Mall of Milpitas, we sent Bay Curious producer Gabriela Glueck to the Mall to meet up with someone who used to work there when it was a Ford plant.

Gabriela Glueck: Standing inside of the Great Mall today, it feels like any other American mall. But it’s got kind of an unusual shape. It’s a rough oval with a band of stores around the outside and a hidden open space in the middle where trucks can drive in shipments. It’s this secret inner area Karl Cortese is most excited to show me.

Karl Cortese: I just kind of know where everything is at.

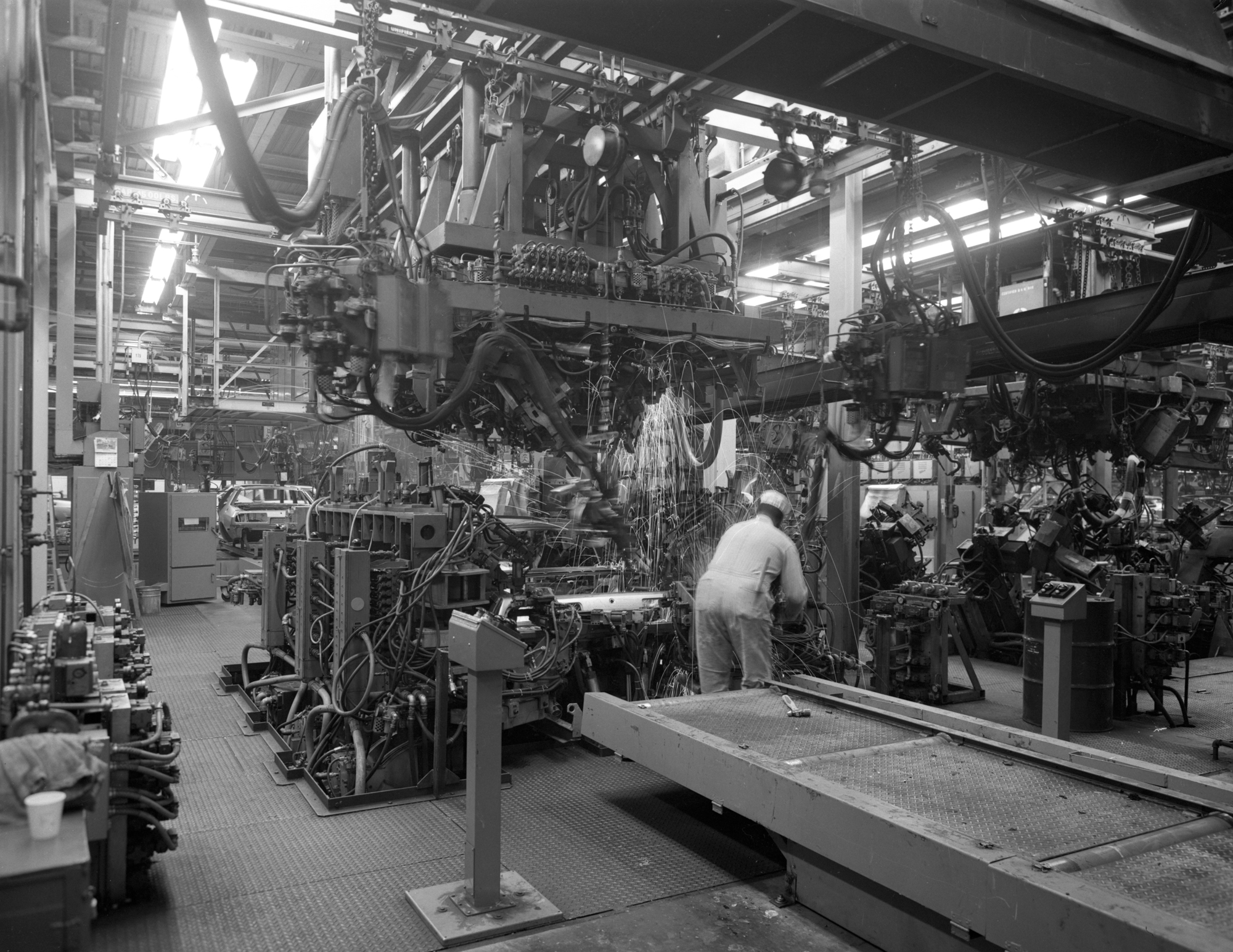

Gabriela Glueck: Karl started working in this building back in 1968 when it was a Ford plant. He spent 15 years sweating on the assembly line.

Karl Cortese: There wasn’t any air conditioning. So I remember that very well, because I used to take it all the way down to my underwear and then put my coveralls on and that’s all I had to wear, because it was so hot in here, so noisy and everything else. So I put up with it like I said for a long time, but it’s okay.

Gabriela Glueck: Walking through the Great Mall with Karl is a strange experience. Where I see a food court, he sees an assembly line.

Karl Cortese: I could tell you small parts here, upholstery was here, trim was over here, chassis was over here.

Gabriela Glueck: It’s like he can still hear the clanging metal, the chatter of workers, the sounds of nonstop progress.

Advertisement: They’re rolling and they’re moving fast. They’re the new Ford trucks 460 with certified economy. And they’re coming off the assembly lines and onto the highways, heading for Ford dealers all over America.

Gabriela Glueck: Talking with Karl got me wondering why Ford decided to build a factory in Milpitas at all. The answer is actually pretty simple. In the 1950s, Milpitas was largely agricultural land. The name Milpitas means “little cornfield” and after World War II, Ford was looking to expand. Ford had already been operating for decades in Richmond, California. During the war, the factory there manufactured tanks.

But post-war, the Richmond plant was just too small and outdated. So in 1955, Ford packed up its boxes and moved to Milpitas, quite the upgrade. The new factory was roughly three times as big. 1,414,000 square feet to be exact. That’s nearly 25 football fields dedicated to making as many cars as humanly possible. I spoke with a handful of men who worked at the Milpitas Ford Factory about their jobs.

Karl Cortese: I put the back hinges on for the three doors and things like that, and the station wagons.

Don Conley: So I was putting in the glass, the side glass, the quarter glass windshield and back glass, wherever they needed me.

Leo Cozzo: I worked in the Mustang, putting the pin stripes on and big emblems and louvers and stuff like that.

John Wilcoxson: I also worked in the repair hole at the end of the production line on cars that had missing parts, damaged parts, that sort of thing.

Gabriela Glueck: Each worker was assigned a station and a task, to repeat, repeat, repeat. One former worker told me it was a job that could turn young bodies into old ones real fast. They worked on all sorts of models, the F-series pickups, the Mustangs, the Falcons and the Pintos.

Pinto Advertisement: The new little car from Ford, moves with a tough little engine that’s not only frisky but thrifty.

Gabriela Glueck: But outside of the factory walls a problem was brewing: a housing problem. When Ford relocated to Milpitas, many Richmond workers came with it, including many of the plant’s African American employees. They needed a place to live.

Herbert Ruffin II: And they’re looking around, and they’re like, you know, okay, so what’s down there? And so how are we going to keep our jobs going back and forth? There is no BART, there is no CalTrain, there is none of that.

Gabriela Glueck: That’s Herbert Ruffin II. He’s an Associate Professor of African American studies at Syracuse University. He also spent part of his childhood in Milpitas. He says an African American worker named Ben Gross was a key player in solving this housing crisis.

Gross was born and raised in Arkansas, lived under Jim Crow laws, and picked cotton during the Great Depression. He joined the army, then joined Ford. He quickly became involved in union politics with the Local 560, a branch of the United Auto Workers Union.

Herbert Ruffin II: Gross believed that he worked on the same lines as everybody, African Americans, and that they should be afforded the same type of treatments.

Gabriela Glueck: Top of mind was housing for Black workers who were barred from buying or renting homes in many towns nearby. Gross was appointed to a special housing subcommittee, tasked with finding a plot of land to build an integrated community. But prior to Ford’s move, Milpitas had been almost entirely white. And not everyone was thrilled at the prospect of change.

Herbert Ruffin II: But at every point in time as this is being developed, there were always like these, these barriers that would be thrown out there. Well, you can’t build this here because of sewage. You can’t do this because of this. You can’t do this because of that, that, that, you know.

Gabriela Glueck: Despite obstacles, Gross and local union members were able to find some old ranch land for a housing development. It would become one of the first integrated neighborhoods in America. And with funding and additional support from a handful of Quaker affiliated organizations, they started to build.

Herbert Ruffin II: When it did open it, and it was a big deal, you know, it was plastered all over newspapers.

Gabriela Glueck: Called Sunnyhills, it opened in 1956, just a year after the factory. Soon families like John Wilcoxson’s started moving in.

John Wilcoxson: We had a Black family on one side of us, a Hispanic family on the other side, and we had a Polish family on the backside of our fence.

Gabriela Glueck: John is white and was young enough that he didn’t realize there was anything special about such a diverse community.

John Wilcoxson: And we knew all of them going in, and my father worked with them. All knew him by name, and it was just something that I grew up with, and I thought was normal everywhere.

Gabriela Glueck: The Union Hall was at the entrance to the neighborhood and pretty much everyone who lived there worked at Ford. John told me there was a real community feel to the place. From the Fourth of July parties to the potlucks.

Neighbors also came together on more somber occasions, like the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In its wake, the Sunnyhills United Methodist Church held a mourning event, with an open conversation about race.

John Wilcoxson: And it wasn’t until I was older and actually we were moving away that my parents told me that – and this is when the ‘65 riots were starting – that not everybody lived in a nice community like we had been in.

Gabriela Glueck: Ben Gross, the man responsible for getting Sunnyhills built, was eventually elected Mayor of Milpitas. He was one of the first African Americans to hold that office in the state of California. Reflecting on his legacy in Milpitas, Gross was quoted in The Peninsula Times Tribune saying that when:

Ben Gross: A citizens’ group said they wanted to change the city’s name, I told them we should change its image instead. We sat down and developed a master plan that brought Milpitas from a small farm community to the thriving city it is today. It’s a city on the move.

Gabriela Glueck: Ford was a big part of this “city on the move.” And many neighborhood kids like John, who grew up in Sunnyhills, ended up working at the factory.

John Wilcoxson: Going into Ford, it was not something I originally had planned on doing, but it was sort of a natural event once it kind of came about.

Gabriela Glueck: For many, working at the Ford plant was a pathway to the middle class, they could buy a home, have a family, and a guaranteed retirement. But all that was threatened when American automobile sales started slowing. John remembers it all too well.

John Wilcoxson: Well it was the late ’70s, and everybody, all the different auto manufacturers, they were producing more cars than they were selling.

Gabriela Glueck: It was a real rough patch for the American car industry.

John Wilcoxson: There was the oil crisis, everything kind of shut back the amount of cars people were buying.

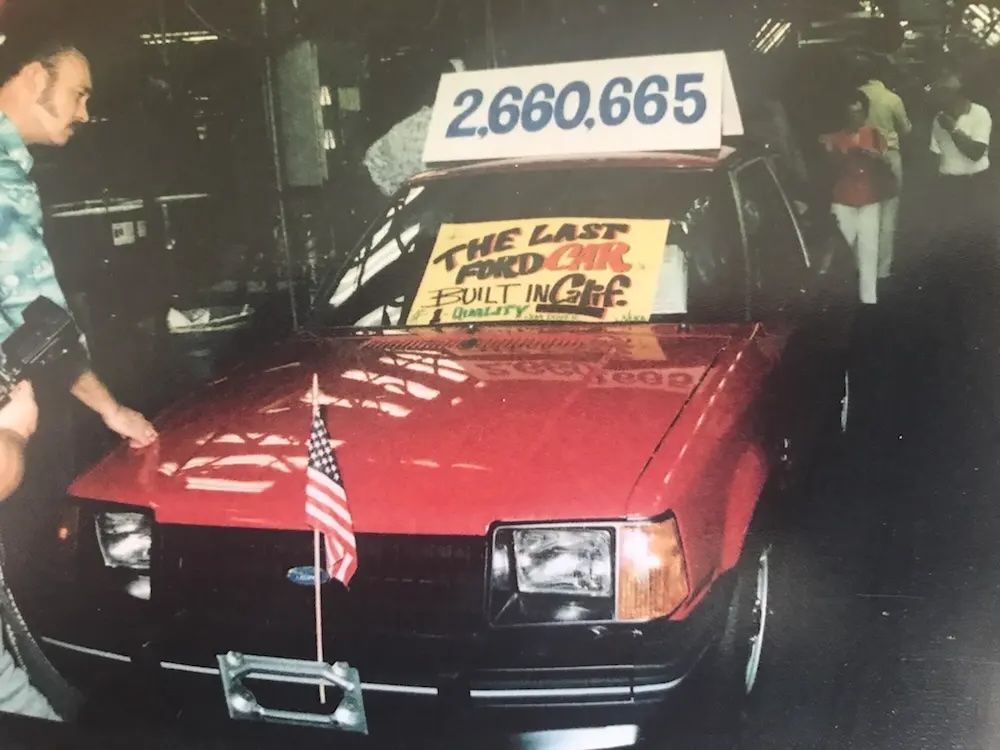

Gabriela Glueck: He remembers seeing last year’s models lined up in the factory lot, Ford had made more than they could sell. It was evidence of a changing tide. In 1983, the factory closed its doors, thousands of well-paid jobs were gone. But this was the hey-day of Silicon Valley and tech companies were bringing a new kind of job to the area. The factory itself lay vacant for a while — nearly 10 years — until it would get the chance to fulfill its second destiny.

KGO-TV: A huge commercial venture that’s opened up hundreds of jobs in Milpitas tied up traffic on the Montague expressway today and sent thousands of people into a shopping frenzy.

Gabriela Glueck: In 1990s America, a massive indoor space like that could only really become one thing.

KGO-TV: And with that, the Great Mall opened its doors today, offering the promise of an economic boom.

Gabriela Glueck: Local TV station KGO was there to cover the mall’s 1994 opening.

KGO-TV: Built on the site of the old Ford Motor Company plant, this monster outlet mall is expected to generate 350 million dollars worth of annual sales.

Gabriela Glueck: It was a festive occasion, people milling around, exploring all the new stores. The footage is grainy, but you can still make out what looks like an old-school Ford car on the floor. A small history exhibit commemorating the factory. These days, that car and the exhibit are no more. But traces of the past still linger, if you know where to look.

Katrina Schwartz: That was Bay Curious producer Gabriela Glueck.

Brandon Choy: Bay Curious is produced in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Katrina Schwartz: Our show is made by: Gabriela Glueck, Christopher Beale, and me, Katrina Schwartz. With extra support from Alana Walker, Maha Sanad, Katie Springer, Jen Chien, Holly Kernan, and everyone on team KQED. Thanks for listening. Have a great week!