Olivia’s mom: [singing] Happy birthday dear Olivia, Happy birthday to you!

Olivia Allen-Price: Thanks, Mom. Some are less welcome, like the startling trill of your alarm clock at 6 a.m. [iPhone Alarm] Or those ubiquitous leaf blowers in many suburban neighborhoods. [Leaf blowers sounds]

Okay, those are both legitimately giving me a stress reaction. But these sounds become so much a part of the soundtrack of our lives it’s hard to imagine a time when we won’t hear them. But if you cast your gaze far enough into the future, that’s almost certain to be the case. It’s probably only a matter of time before any given sound becomes… lost. I’ve been thinking about this a lot ever since we got this question from longtime listener Brent Silver.

Brent Silver: I’m interested in learning about what sounds are no longer heard in the San Francisco Bay Area, that used to be heard by people living here?

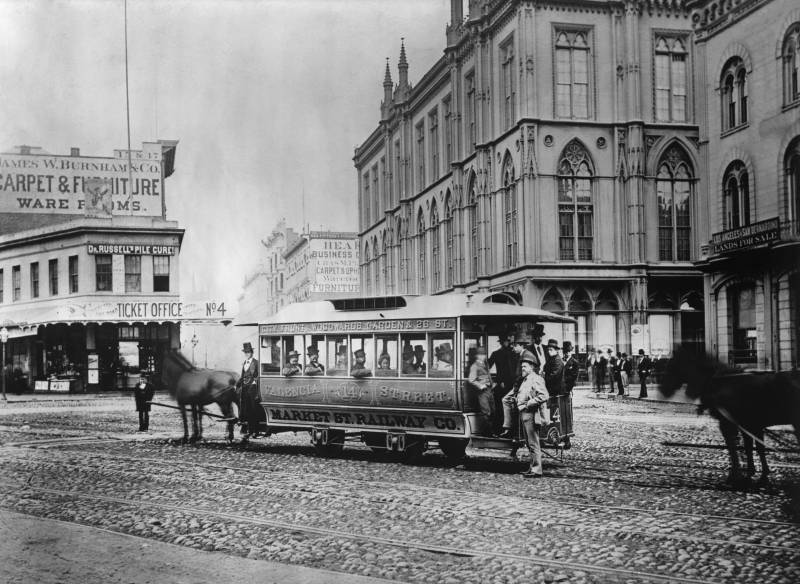

Olivia Allen-Price: He was inspired by that famous silent film clip going down Market Street in San Francisco just before the massive earthquake and fire of 1906. If you haven’t seen it, definitely go check it out. On YouTube, you’ll find the footage paired with an imagined, but pretty credible soundtrack.

Brent Silver: They showed people on horseback and in carriages and on trolleys, and there was sound attached to it. Which made me think about what a modern drive down Market Street sounds like today and how different it is.

Olivia Allen-Price: No clip-clopping of horses, but the hydraulics on a Muni Bus instead…

[sound of Muni bus brakes]

Olivia Allen-Price: This week, we’re digging into the archives to find some of the “lost sounds” of the Bay Area – most of which you’ve almost certainly never heard. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. This is Bay Curious. Stay with us.

[SPONSOR MESSAGE]

Olivia Allen-Price: OK, so Brent wants to dip into the archives to explore some lost sounds of the Bay Area. But, let’s be honest here. The number extends to something like infinity. So, here to walk us through a few is KQED’s Rachael Myrow.

Rachael Myrow: I’ve done a lot of Bay Curious stories over the years, but Brent’s question threw me for a loop. Think about it: You need the backstory behind each lost sound, to understand what’s special about each one. What it was, when it was, why we don’t hear it anymore, and why we should care. So I called Brent up and asked him to elaborate.

Brent Silver: I was curious to learn whether there are any other sounds besides, maybe horse steps, that are not something that people hear on their day to day experience. And as I started thinking about it, I thought of other examples.

Rachael Myrow: Do you have favorites?

Brent Silver: Obviously, the sound of technology has changed, so we no longer hear rotary phones. [sound of rotary phone rotating]

Brent Silver: Umm, the bells and whistles that you might hear on cable cars and trolleys are different. [cable car bells]

Rachael Myrow: No doubt, Brent. We’ve been through several generations of cable cars and trolleys now, as that history started in 1873. He had more ideas. So many ideas! This turns out to be a huge question, Brent.

[sound of rotary phone rotating]

I decided to dial up – well, metaphorically speaking – Sam Green, a documentary filmmaker who lived in San Francisco for 20 years, from the early 1990s to the early 2010s.

Sam Green: I love San Francisco and I love sounds, so this is all fun and exciting…

Rachael Myrow: Green made a movie called “32 Sounds,” released in 2022, so he loved this question from Brent about evocative old sounds from the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond, many of which are lost to time.

Sam Green: People you loved who are gone… Their voices still exist, somewhere in you. So there’s that, and then there are sounds you never heard, but you know about, you know, you can imagine. Those are different things, I think. But related.

Rachael Myrow: I love that idea about “lost sounds” including the sounds of people who don’t exist anymore. Like, here’s a clip of my Grandma Bea, singing to my dad when he was two years old.

Grandma Bea: There is a little boy, whose name I do not know, [child babbles] He stands on the corner every night, night, night.

Rachael Myrow: It’s not just that my grandma and my dad aren’t here any more, but you also hear in those voices the lost worlds they existed in. Because people– their accents, the way they lived and thought– makes a place, as much as any technology does. As it happens, Green’s personal list of favorite lost sounds of San Francisco includes just such a lost voice, Harold Gilliam’s voice. He was a San Francisco-based environmental journalist who wrote for the Chronicle and the Examiner. Gillam died in 2016 at the age of 98, and Green interviewed him for another film in 2013, about fog in San Francisco.

Harold Gilliam: Giving a sense of the Bay, that there are ships out there in the Bay, that the ocean is rolling out there, and that the earth is turning.

Sam Green: Often people just say, sort of like, predictable things, and he started talking about the foghorns late at night, and being awake, and how that made him feel a connection to the tides, and the mariners out on the Bay, and the spinning of the earth and the changing of the seasons, and it’s a powerful thought and a beautiful thought.

Harold Gilliam: It’s a deep feeling that’s hard to explain. A feeling of community with the turning of the earth and the apparent motions of the stars, and the motions of the tides.

Rachael Myrow: Gilliam was one of those people who helped describe and define the city for others. His columns – and interviews – explained a lot of the natural phenomena we observe around us but don’t necessarily understand, that are nonetheless moving us in profound ways.

[foghorn rings]

The foghorns are perhaps the most iconic sound attached to San Francisco and thankfully one that is not lost yet, even as technology has relegated them to more of a backup system.

Speaking of backup systems, here’s one that doesn’t work anymore. The San Francisco Outdoor Warning System, AKA the Tuesday noon siren.

[siren wails]

Rachael Myrow: Brent also asked about this one, which is a lost sound because the 119 sirens have been silent since late 2019, due to cybersecurity concerns — and really, the city’s failure to fork over the money for a revamp. Green, like many people who’ve lived in San Francisco, recalls the sirens fondly.

Sam Green: There’s speakers all over the city and it would be this weird voice saying, like, “This is a test.”

Voice over loudspeaker: This is a test of the outdoor warning system. This is only a test.

Rachael Myrow: Of course, people and defunct technologies are just two categories of lost sounds. Another key category–music. Green made a short film about a musical group that many fans think are distinctively Bay Area. It’s called “Meet the Kronos Quartet.”

[classical music]

This string quartet based in San Francisco for 50 years with a rotating cast of musicians is famous for their passion playing — not just classical music — but many other kinds, too. Green loved their early sound, with the original musicians.

Sam Green: We would travel together all over the world, showing this film together. It was a film that didn’t exist on Netflix or YouTube. And every time we’d do it, I would sit there on stage and listen to them play. And it just was, you know, it never got old. It was always a deep and profound thrill.

Rachael Myrow: Let’s power through a couple more lost sounds I found while nosing around for this story– sounds few people who were there are still alive to remember. They’re from San Francisco’s radio airwaves, long gone here on earth though still out there somewhere, travelling deep into outer space.

Here, for instance, is Paul Robeson, the iconic bass-baritone singer and social justice activist, recorded giving a speech in May of 1946 to the Marine Cooks & Stewards Union during a banquet held in his honor.

Paul Robeson: I come from a slave father. Not grandfather, a slave father, born in Eastern North Carolina in 1843. Escaped from slavery in 1858. A contemporary co fighter with Fredrick Douglas, Harriet Tubman, John Brown, Sojourner Truth and William Lloyd Garrison.

Rachael Myrow: Would I have loved to be a fly on the wall in that hall, just to see him speak live. Among other things, Robeson praised that union for its progressive efforts to organize around racial equity– another reminder that social activism in the Bay Area didn’t start in the 1960s. OK, number two, here’s something that used to be quite common in San Francisco, but now, not so much: LIVE jazz on the radio.

[Jazz ensemble playing]

Rachael Myrow: This is the Anson Weeks Orchestra, playing the 1929 hit song, “Singin’ in the Rain.” From 1929 to 1932, the Anson Weeks Orchestra broadcast weekly from the Mark Hopkins Hotel, which as luck would have it is still there, on the top of Nob Hill.

I gotta thank you, Brent, for sending me down this particular sonic rabbit hole. The journey got me thinking about how at any given point in time a city’s soundscape, like that of San Francisco’s, is an ephemeral blend of its people and the technologies they used to move through their days and the music that formed the soundtrack to their lives. Right now, at this very moment, we’re all awash in sounds that will recede into the mists of memory as we travel on this river of time that never passes the same way twice.

[Collage of sounds]

Olivia Allen-Price: That was Rachael Myrow, Senior Editor of KQED’s Silicon Valley Desk.

We are deep into planning for the podcast in 2025, and we’d really like to do some stories about climate change. So if you’ve got a question about how it’s affecting the Bay Area, or steps we can take to solve it that impact anything from the energy we use, the transit we take, to the food we eat – we are all ears. Submit your question at BayCurious.org.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. In this giving time of year, please consider becoming a KQED member. Donations of any size make a difference and help support programs like this one. Thanks!

Bay Curious is made by Amanda Font, Ana De Almeida Amaral, Christopher Beale, and me, Olivia Allen-Price. Extra support from Kaitie Sprenger, Jen Chien, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan, and the whole KQED family.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Have a wonderful week!