Warning: This story contains graphic language, and descriptions of violence and suicide.

W

hen Lili Steele got home from work on that hot, humid evening in August 2021, she expected to find her husband, Sgt. Kevin Steele, sitting at his desk working on his book. The couple had moved to a rural area near Missouri’s Lake of the Ozarks after Steele had taken a leave of absence from his job as an investigator in a high-security prison in Folsom, California.

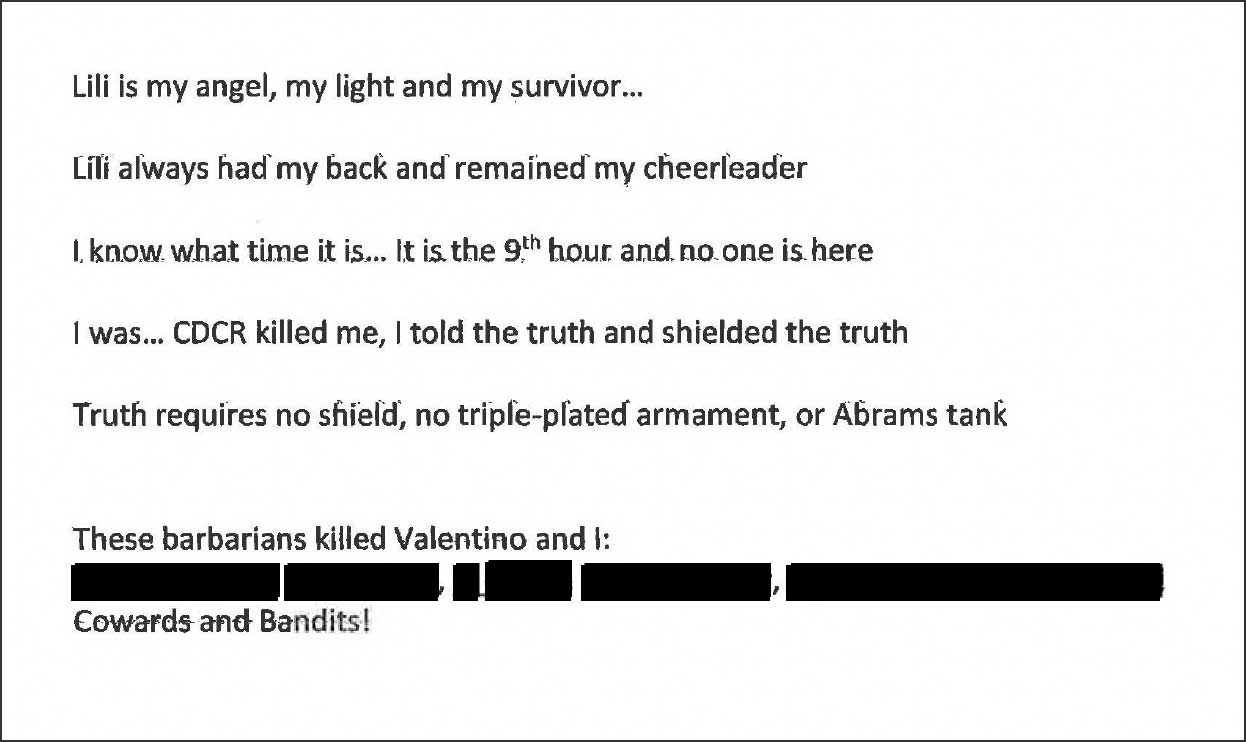

Writing the book, Lili said, “was his new job.” The manuscript chronicled Steele’s decade at the prison, where he had become increasingly frustrated with a system he came to see as corrupt and antithetical to his deep Christian faith. His project had an ominous working title: The Thin Line Blurs…How to Kill a Cop…Betrayal.

But the 56-year-old wasn’t at his desk.

Lili called Steele’s phone and found it ringing on the kitchen counter. She started to panic; she knew her husband had been struggling. Months earlier, he’d told her that he was haunted by a “trailer of dead people.” Some were soldiers he’d served alongside in Iraq who hadn’t made it home. The rest were from the California State Prison, Sacramento, known colloquially as New Folsom.

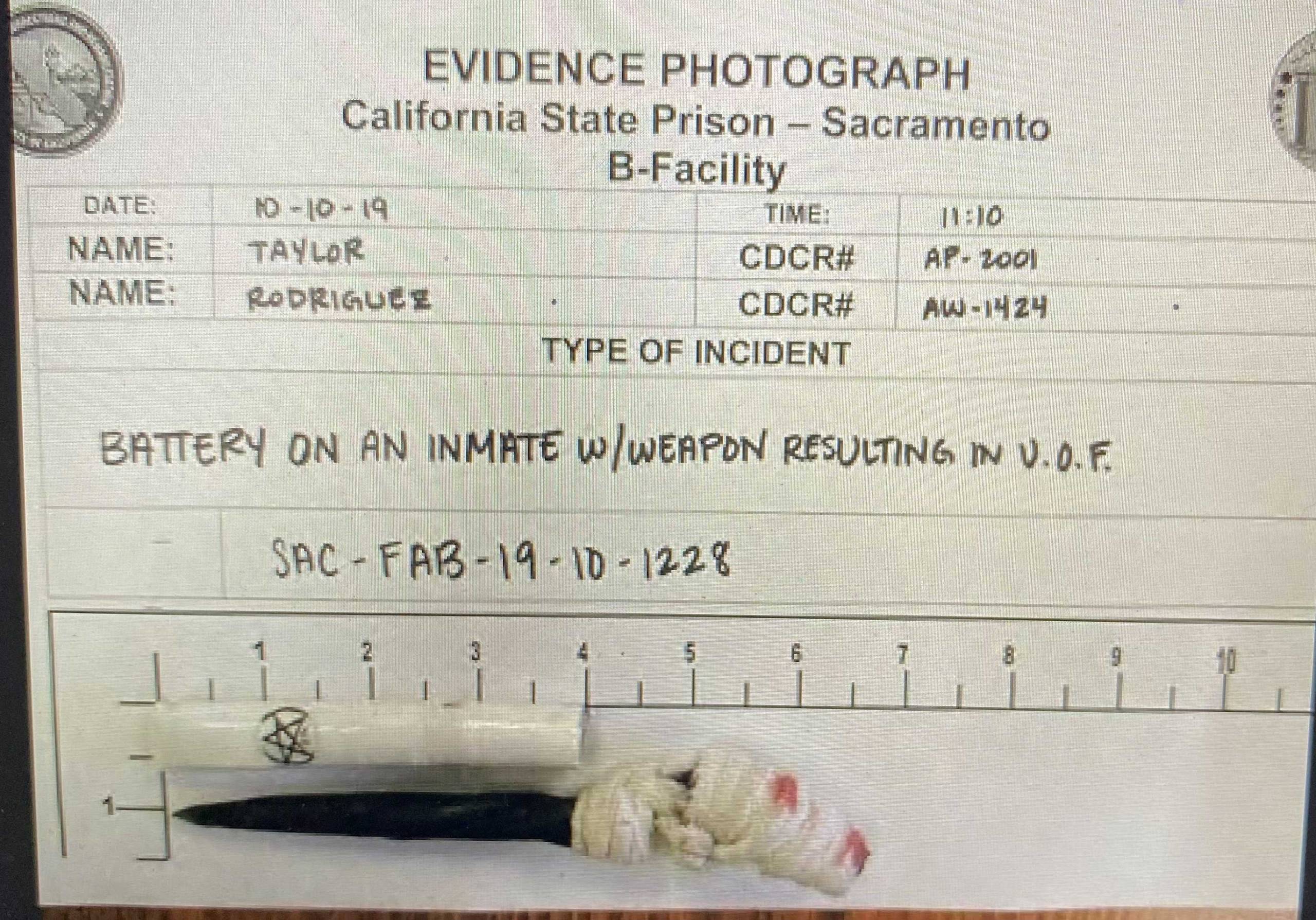

There was Ronnie Price, the 65-year-old whose arms were shackled behind his back when correctional officers slammed him to the ground, fatally injuring him. There was Luis Giovanny Aguilar, the young man who’d been stabbed to death by two other incarcerated men in full view of officers. Finally, and perhaps most painfully, there was his friend, officer Valentino Rodriguez Jr., who’d died of a fentanyl overdose six days after blowing the whistle on fellow officers for alleged misconduct.

“Kevin, you didn’t kill those people, you tried to help,” Lili remembers telling her husband. “You followed the protocol, the chain of command. You told the people in charge. It’s up to them to carry the ball now.”

After searching the house, Lili walked from the open garage across their driveway to a red storage shed. That’s where she found her husband already dead. Steele had hanged himself.

In a recording of the 911 call, the dispatcher can be heard asking Lili if her husband had been sick.

“No,” she sobbed. “He’s been dealing with a lot of stuff from his work.”

Considered in isolation, Steele’s suicide might have been chalked up to one man’s struggle, but the timing — less than a year after the death of his friend Rodriguez, who worked in the same elite unit — points at something larger. A multiyear KQED investigation and an eight-part podcast called On Our Watch found a persistent code of silence among New Folsom officers that went largely unchecked by prison leadership and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). An exclusive analysis of hundreds of internal use-of-force records, dozens of leaked documents and videos, and interviews with current and former CDCR officers revealed a culture of cover-ups that enabled the abuse of incarcerated people, officer-on-officer harassment and at least two homicides at the prison.

A spokesperson said in an email that CDCR “maintains a zero-tolerance policy on code of silence” and that the agency “is fundamentally reforming its approach to addressing allegations of staff misconduct to enhance staff accountability and improve transparency.”

Over the past year and a half the agency declined KQED’s multiple requests to interview New Folsom’s outgoing warden, Jeff Lynch, and the head of the agency, Secretary Jeff Macomber, who served as the warden there from 2013 to 2016. The agency also did not respond to a request to speak with Jason Schultz, who was appointed acting warden in November. CDCR representatives have repeatedly declined to answer questions about the high rate of use of force at New Folsom. They said they could not comment on specific allegations made by Steele and Rodriguez before their deaths.

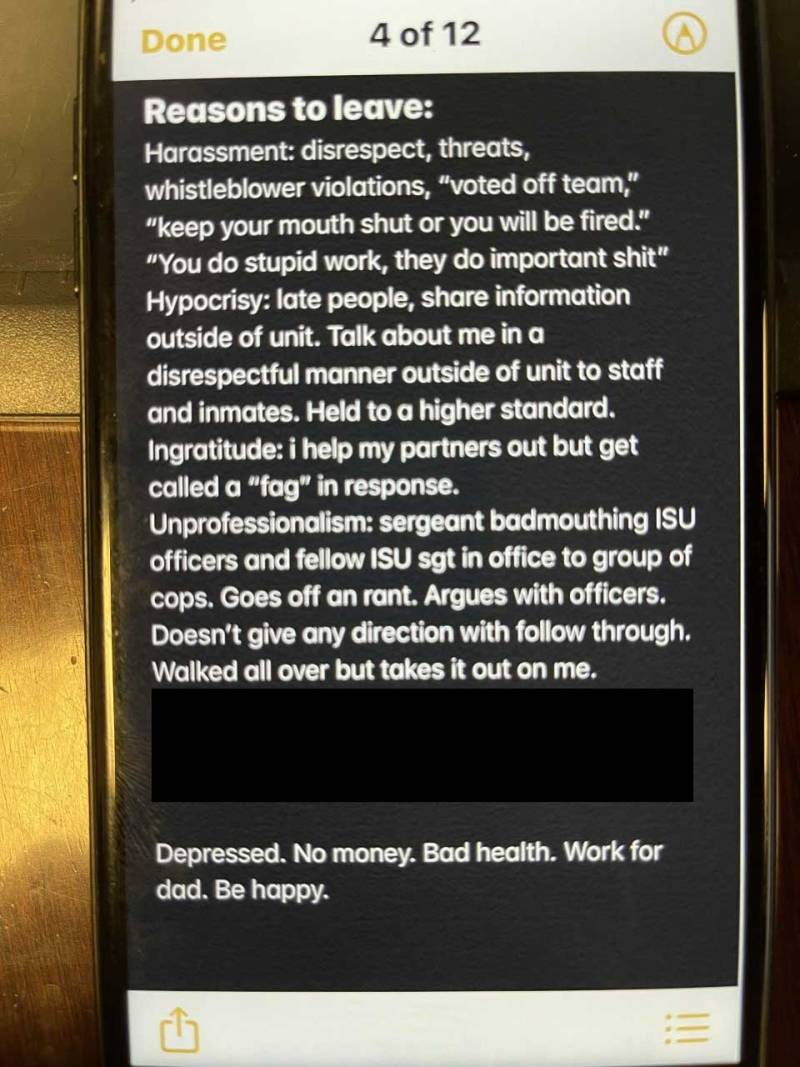

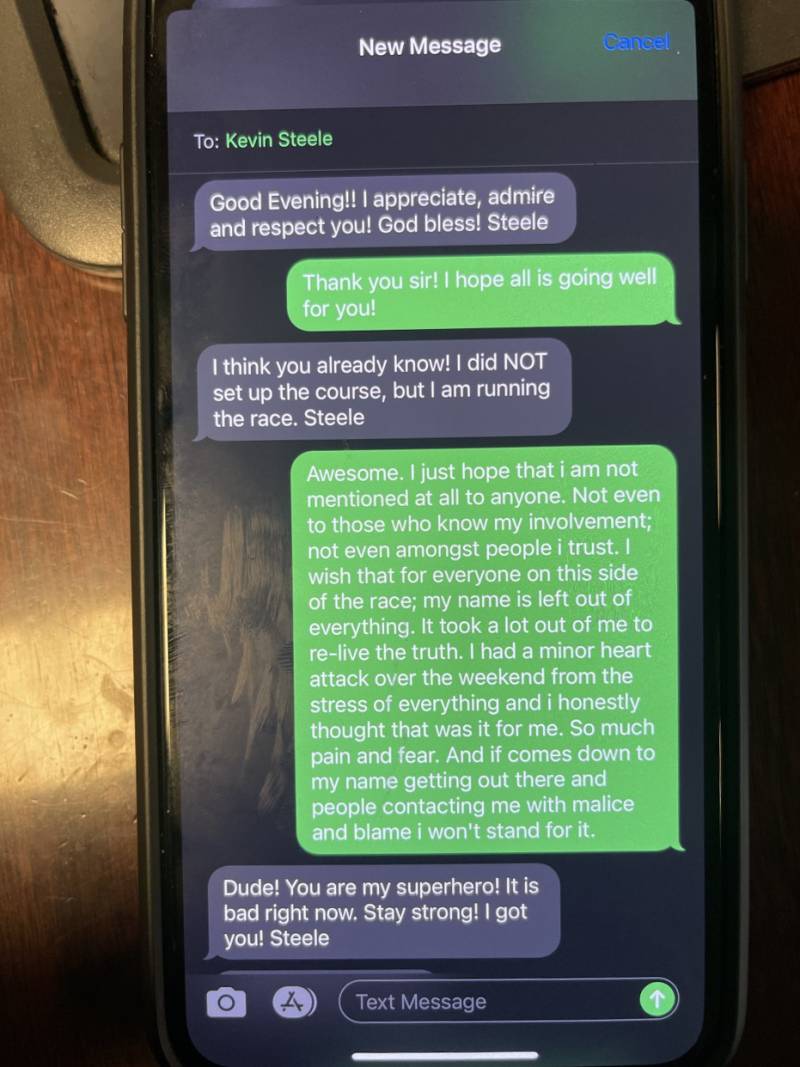

But a trove of written and recorded materials left behind by the two officers and obtained by KQED details their fear of retribution and sense of despair as they tried to expose misconduct in their institution.

Outlier

Steele started off as a true believer. Hired by CDCR in 2001, he was initially assigned to San Quentin before transferring to New Folsom in 2008. Sprawled along the American River just outside Sacramento, the prison houses about 2,200 people, many of whom have mental health needs or have been convicted of the most serious crimes.

Working as a correctional officer appealed to the sense of duty and service Steele had enjoyed in his Air Force career, while also promising good benefits and opportunities for advancement. The sergeant’s brother, Michael, said he liked to claim that nobody “worked harder than a Steele.” If his shift started at five in the morning, he’d arrive at four. Each day on his way into New Folsom, Steele walked past the Gothic green tower of the adjoining old Folsom prison (made famous by Johnny Cash) carrying his lunch in a clear plastic bag through the checkpoint of the newer facility. Once he clocked in, “he didn’t stop moving,” said Steele’s colleague, retired correctional officer Annette Eichhorn.

Prison leadership entrusted Steele with a lot of responsibilities, from drug testing officers to leading annual trainings. In 2015, he was promoted to prosecution coordinator in the Investigative Services Unit (ISU). Known among officers and incarcerated people as the “squad,” the specialized team serves as the police force for the prison, investigating crimes committed by prisoners and complaints against staff, including for excessive use of force.

Officers can lawfully use their hands, batons and even the weight of their bodies to subdue prisoners who resist, or ignore their commands. They can deploy less lethal weapons like pepper spray and foam bullets to stop fights or break up riots. If someone’s life is in danger, officers can respond with deadly force. In general, force has to be proportional to the threat, and cannot be used after a threat has been subdued, or as retaliation or punishment.

Even among high-security prisons, where violent encounters with staff are most common, New Folsom stands out: It had the highest overall use-of-force rate of any California state prison from 2009 through 2023, according to an in-depth analysis of CDCR reports published by researchers at University of California, Berkeley, in partnership with KQED. CDCR has not yet posted all the data for this year, but numbers released so far show that use-of-force rates at New Folsom remain the highest in the state.

New Folsom has been even more of an outlier when it comes to the most serious cases — those in which officers use deadly force or badly injure incarcerated people. KQED’s exclusive analysis of investigative records from 2014 through 2019 revealed that New Folsom had three times as many of these cases as any other prison in the state.

A CDCR spokesperson told KQED last year that she took issue with KQED’s analysis of general use-of-force data, but the agency did not respond to further detailed requests for clarification and questions regarding these findings.

Warden Jeff Lynch appeared unaware of an unusual level of officer violence at New Folsom. Asked about it during a media tour of the facility in April 2023, he said use-of-force rates at his prison were “probably pretty similar” to other high-security facilities in California.

But over the years, Steele had raised grave concerns about officer violence to prison leadership. It was part of his job to collect the statements of prisoners who’d been injured by guards, and he’d noticed a troubling pattern.

A cover-up

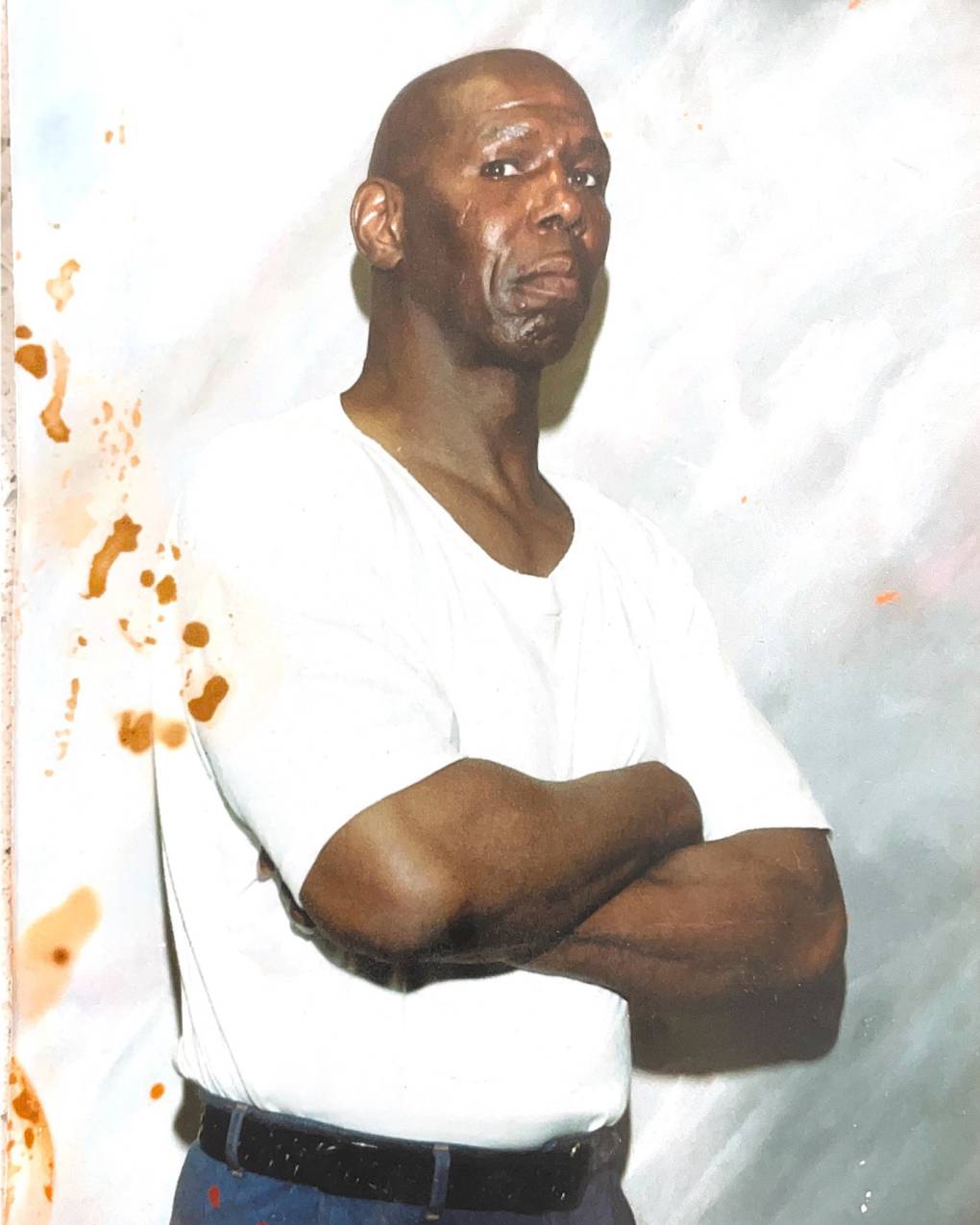

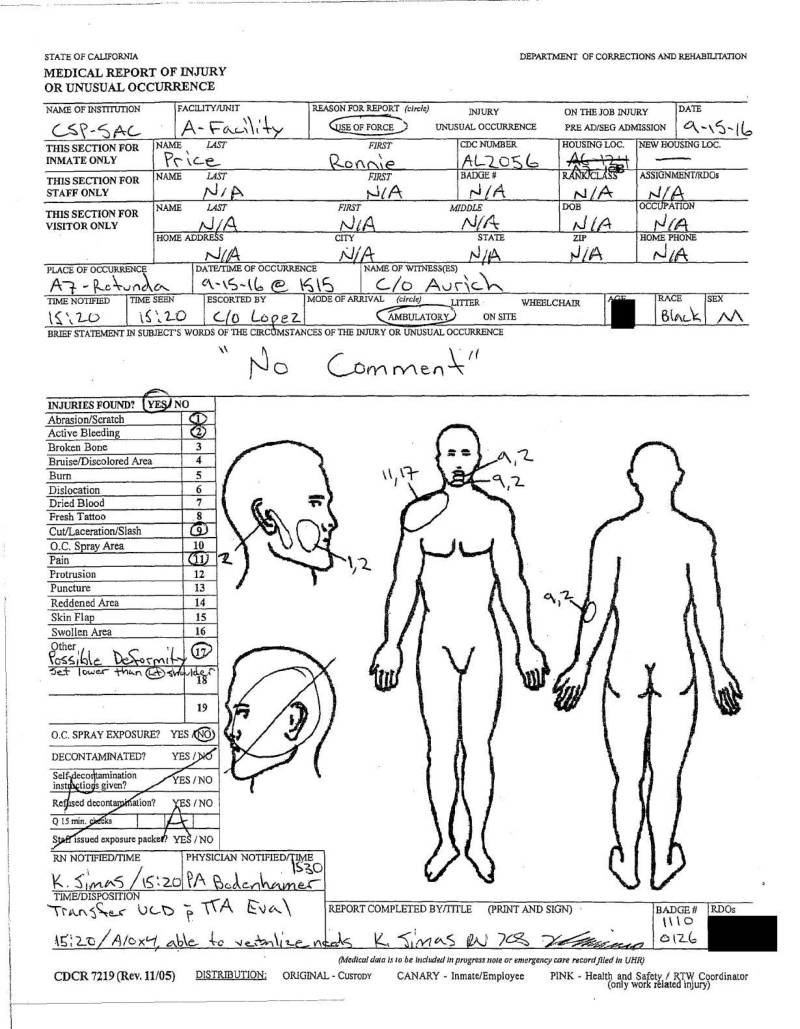

On Sept. 16, 2016, Steele interviewed 65-year-old Ronnie Price as he lay handcuffed on a gurney in the hallway of the UC Davis Medical Center with visible trauma to his face that included missing teeth and a broken jaw.

In his unfinished book, Steele wrote that he expected to find a “combative, disruptive and quarrelsome inmate,” but instead found Price “pleasant and amicable.” Steele recalled Price telling him that officers had tried to force him to move to the cell of an active gang member, which Price feared would mean trouble.

In a recording of the interview acquired by KQED, Price told Steele that during the escort he passively resisted officers, who then shackled his feet together. His hands were already chained behind his back. As they walked him through the rotunda of the housing unit — an area not covered by surveillance cameras — Price said an officer stepped on the chain between his ankles, causing him to fall face-first onto the cement floor. Price told Steele that as he raised his head to spit out his bloody teeth, “Somebody grabbed my head and slammed it into the ground.”

The next day, Price died of a pulmonary embolism related to his injuries, according to the coroner’s report. Steele attended the autopsy and then contacted his bosses. “I was very specific when I advised the administration and my supervisor that I believed that staff were responsible for the death of Inmate Price,” he writes in his book.

Internal documents obtained by KQED through a public records request show that officers wrote the incident up to make it look like Price posed an active threat, claiming that he’d “spun to his left, and lunged forward breaking free” of the escort and that “immediate force” was used “to overcome” resistance.

But after lengthy investigations by the FBI and CDCR, five officers and a sergeant would lose their jobs, and three of them would be convicted of federal charges related to excessive force and efforts to cover up the truth about Price’s death.

It is exceedingly rare for officers to be disciplined for injuring people in California prisons, but Steele believed the Price cover-up was not an isolated incident. Over the next year, he reported at least two more incidents in which officers’ version of events failed to explain the severe injuries of the men he spoke to. Joel Uribe and Ramiro Navarro, independently made strikingly similar allegations in their use-of-force interviews with Steele: During separate escorts, officers had stopped in an area not covered by surveillance cameras and badly beat them.

“Please don’t think I’m exaggerating,” said Uribe, 50, who’s still in prison but no longer at New Folsom. “They really wanted to have me killed.” Uribe told KQED he was targeted because staff wrongly suspected that he had helped provoke an attack on an officer. Navarro, 56, said in a phone interview from prison that officers punched and hit him with a metal tool. He told Steele the last thing he remembered before he “passed out” was an officer kicking him in the head. Both men were in restraints for the escort, according to case documents, and denied provoking the officers’ assaults.

But an officer claimed in his report that Uribe “spun around” and struck out with a walking cane, at which point the officer used “immediate physical force to overcome resistance, subdue an attack and effect custody.” A supervisor wrote that after Navarro “aggressively swung his head” in an attempt to headbutt them, officers used “the minimal amount of physical force needed to place Navarro in a prone position.”

Documents show that Uribe suffered a concussion, broken ribs, and a face laceration; he told KQED he still has hearing loss in one of his ears. Navarro’s ribs were also broken, and doctors inserted a chest tube to drain blood from around his lung, reports show.

Despite internal investigations and formal complaints made by Uribe and Navarro, no officers were ever disciplined. Instead, documents show that both prisoners were written up for the incidents; each said they were sent to solitary confinement for a year.

In all, a dozen men who were incarcerated at New Folsom told KQED that officers had used force as retaliation for causing trouble, submitting complaints or even attempting suicide, which triggers a protocol that means extra work for officers. Many of these men had filed formal grievances, but to little effect. Internal reports documenting serious use-of-force incidents at New Folsom from 2014 through 2021 show that, aside from the case involving Price, only one other incident resulted in discipline for an officer, who CDCR fired for using a prohibited chokehold.

Unlike Steele, many CDCR employees chose not to speak up. Four current and former correctional officers — who asked KQED for anonymity because they feared for their job security or physical safety — said that it was well known that some officers would beat up incarcerated people. Each said they witnessed at least one of these beatings firsthand, but did not report misconduct due to fear of retaliation from their fellow officers or supervisors.

“I’m sorry that we were too fearful to do the right thing when we were there,” said one retired officer. “But to live under that kind of fear, I can’t explain to you.”

Sgt. Kevin Steele conducted use-of-force interviews with incarcerated people; subjects’ faces were redacted by the agency. Edited from video footage obtained from CDCR via public records request. (Annie Fruit/KQED)

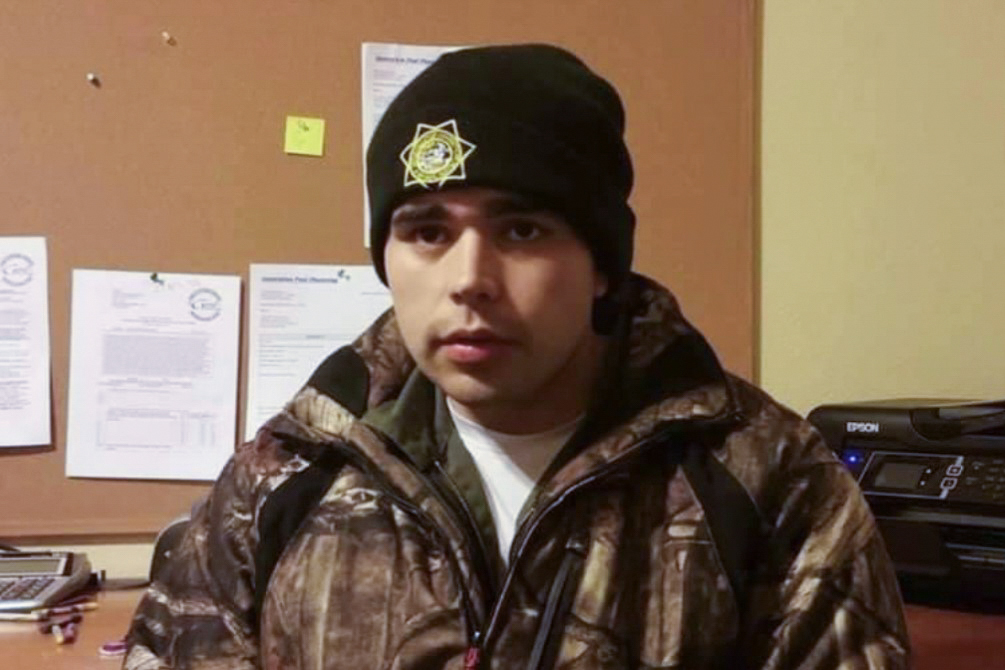

The rookie

In late 2018, correctional officer Valentino Rodriguez walked into the ISU office for his first day on the job. Steele writes in his book that the 28-year-old was “fresh-faced and eager to overachieve.” Rodriguez had stopped by Adalberto’s Mexican Food that morning to pick up breakfast burritos for the whole team — an office tradition by which new members would gain acceptance into the squad. But as the morning wore on, the offering was ignored; to Steele this was a deliberate snub, and he’d see it as an omen of what was to come.

Officers often wait years to get tapped for the squad. Rodriguez had earned kudos as a sharp report writer and a hard worker, but he was relatively inexperienced. Some in the unit thought he’d “skipped the line,” according to officers’ later testimony in a disciplinary hearing. They began calling Rodriguez “half-patch,” suggesting he hadn’t fully earned the special black and green badge of the ISU uniform.

In contrast, Steele welcomed the new guy. In his book, he describes thanking Rodriguez for the food that first day and taking an extra burrito home “so as not to waste his act of kindness.”

The two men worked in different divisions of the squad — Steele was in Criminal Prosecution while Rodriguez had been assigned to Security and Investigations — but Steele always had a positive word for the younger officer. “You inspire me!” Steele texted him on more than one occasion. Sometimes, on the weekends, they’d carpool to law enforcement seminars where they could brush up on the latest drug interdiction tools or California’s prison gangs. And Steele became a lifeline for Rodriguez when he needed advice.

But the coldness from Rodriguez’s closest teammates soon turned to open hostility, according to KQED’s review of text messages in Rodriguez’s phone. One officer in particular, Daniel Garland, taunted him regularly. He called him “fag,” and told him to “sukadik” on a group chat. Garland did not agree to speak to KQED for this story, but his attorney said her client’s actions did not rise to the level of harassment.

Rodriguez’s direct supervisor, Sgt. David Anderson, who was on some of the text threads, did not intervene (Anderson later told investigators “I should have stepped in,” according to public documents). Rodriguez complained in a text to another officer that Anderson would bad-mouth Steele and other senior officers in front of his subordinates, and then threaten to throw Rodriguez off the squad if he said anything. Rodriguez told his fiancée, Mimy, that his supervisor once put his hands around Rodriguez’s neck and told him he could “make it look like an accident.”

Anderson, who was promoted to lieutenant in 2022, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. He told investigators that he treated Rodriguez the same as everyone else, and did not believe the young officer had been offended by what he characterized as “banter.”

CDCR has a “zero tolerance” policy for discriminatory language and harassment. But in reviewing 80 cases of officer discrimination going back to 2015, KQED found that misconduct rarely led to firing, even in instances that involved unwanted touching or threatening a subordinate.

Amid the violence and chaos of a maximum security prison, where trust is essential for officers’ safety, Rodriguez didn’t feel his team had his back. He complained to a friend over text that his colleagues refused to help him with an arrest, and that they disparaged him in front of prisoners; he said that the only person he trusted was Steele.

Steele was only partially aware of what was going on with Rodriguez, but he later told investigators that he noticed his friend would duck into the bathroom nearly every day before his shift. When Steele asked if he was OK, Rodriguez confided that his stress was so intense he often had to vomit before he went into the ISU. Steele recalled Rodriguez saying, “They just never stop teasing me. They don’t ever stop.”

Despite this, Rodriguez continued to seek his colleagues’ approval — texting the group about his efforts to lose weight or a big drug bust he pulled off. Rodriguez’s father, Valentino Rodriguez Sr., told KQED he now regrets raising his son to be so eager to please and quick to forgive.