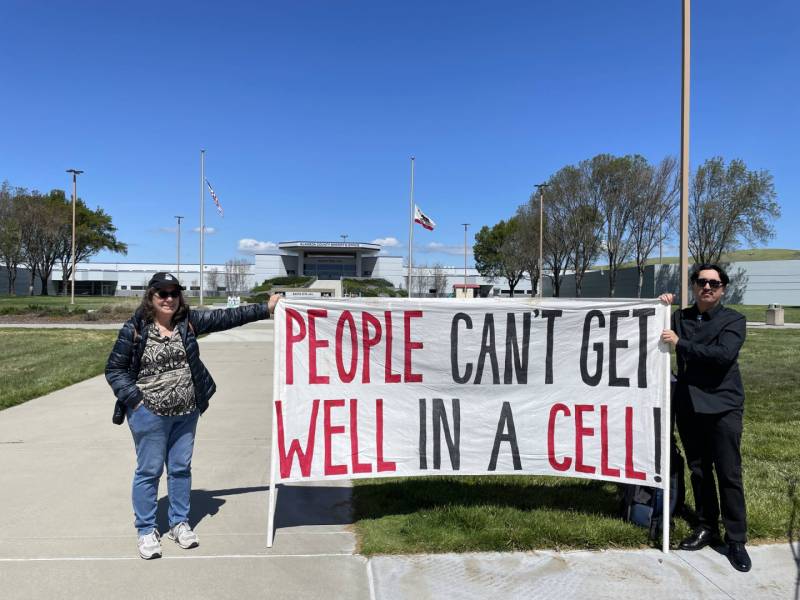

Over 70 people from civil rights groups and families of those affected by mental illness and incarceration held a vigil and noise demonstration organized by the Care First Community Coalition on Saturday to grieve and protest a spate of recent deaths at Santa Rita Jail, Alameda County’s main adult detention facility.

Community and Civil Rights Groups Hold Vigil and Rally Over Recent Deaths at Santa Rita Jail

The Dublin-based jail is not only one of the largest detention facilities in the United States, it is also one of the most notorious, where major health and safety violations have been reported and where over 66 people have lost their lives since 2014. So far this year, there have been four deaths at Santa Rita Jail.

“All four of those people died needlessly within days of their intake,” said Joy George with Restore Oakland, a community advocacy group. “They died after being evaluated … even though there were multiple red flags. They should have been diverted. They should have been elsewhere. They should not have been incarcerated at Santa Rita Jail.”

The facility was placed under federal supervision in 2022 for at least six years to improve conditions for those experiencing mental illness. During the rally, protestors read the names of those who had died in the jail over the last nine years.

While some of the deaths have been attributed by jail officials to suspected fentanyl overdoses, protesters say the majority generally were caused by people not getting the care they needed (whether for mental illness or substance use disorder) in the facility.

“In the event that I’m out of control with a drug habit, should you take me to a drug program or should you take me to jail?” said Dorsey Nunn, executive director of the nonprofit Legal Services for Prisoners With Children. “At a certain point there is something called compassion, and we are sorely missing it as a society, particularly when it comes to Black and brown folks.”

Advocates with the Care First Community Coalition pushed for the “Care First, Jails Last” policy resolution that was adopted by Alameda County in 2021, which set goals for law enforcement agencies in the county to stop the practice of arresting and jailing people dealing with mental health and/or substance use issues. The resolution also called for creating a community-led process to establish behavioral/mental health care and social services. The coalition demanded that the Alameda County Board of Supervisors investigate jail deaths and provide over $50 million for mental health services that were promised but have yet to be implemented. A meeting with the board about budget presentations will be held on April 11.

“The last time my brother Donald Nelson was able to walk, it was walking into this facility … that was May 1st, 2020,” said Norma Nelson. She said her brother, Donald Nelson, died after he was fatally assaulted in a holding cell by another detainee just hours into custody. “Losing a loved one who needs medical and mental health care while in the hands of our social and criminal justice system cuts to the heart with a different kind of pain — it’s deep.”

Nelson added that the sheriff’s department didn’t acknowledge the murder publicly until a reporter months later reported it. Lt. Tya Modeste, public information officer for the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office, said she was aware that the jail’s “reputation wasn’t great in the past” and that “people found out their family members passed away by hearing it on the news,” but she says they’ve been working hard under the new sheriff, Yesenia Sanchez, to turn that around.

“We welcome peaceful protests and understand that the community and families are frustrated,” said Modeste. “It’s difficult to see someone lose their life … We’re not just sitting back and watching people die in our custody.”

Modeste outlined various initiatives the Sheriff’s Office has taken, including building a focus group and inviting community members to discussions with the executive staff and Sanchez about grievances; working with federal monitors and attorneys who represent the incarcerated population on federal oversight; working collectively with community-based partners; sending out press releases when someone dies in custody; and getting in touch with families.

“We’re putting policies and practices in place so that we can make sure that when something like this happens, that we look at our policies, we look at our practices, we look at our services,” said Modeste. “We invite all the stakeholders to the table so that we’re discussing this together and we’re looking at ways to make sure we’re providing better service for our incarcerated population. Sheriff Sanchez is committed to restoring public trust. She’s committed to making sure that we’re being absolutely transparent.”

Katy Polony, a family advocate who works with Families Advocating for the Seriously Mentally Ill (FASMI), says there’s a need for more hospital beds, supportive housing, continuum of care and case management teams.

“Families are getting no support, no training, nothing. When their kids are cycling through the system, they’re like, ‘What do I do? What am I doing?’” said Polony. “The most important thing with someone who has schizophrenia or another psychotic disease is to treat them right away. We need early intervention programs, which means a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a vocal rehab … We could do it, but we don’t.”

Tiffany Monk says her brother who had schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and high blood pressure died in Santa Rita Jail, but that the lack of communication and cooperation from the authorities means she’s still not sure exactly what happened to him.

“I’m hoping [the new sheriff] makes a difference, that she takes her job seriously and holds these people accountable, because it’s not right,” said Monk. “They’re killing people and it’s like nothing’s happening.”

The average daily population at Santa Rita Jail fell to 2,108 in the fourth quarter of 2022, according to a survey by the Board of State and Community Corrections (PDF), while on April 2, the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office reported a population of 1,778.

The Care First Coalition has been calling for the reinvestment of funds from the jail into community-based mental health and substance use.

“The federal court decree requiring county investment in increased staffing of the jail is based on an estimate of 3,000 prisoners, which Santa Rita has not had since 2014,” said John Lindsay-Poland of American Friends Service Committee.

This story has been updated to include the latest average daily population figures for Santa Rita Jail, and a comment from John Lindsay-Poland of American Friends Service Committee.

KQED’s Annelise Finney and Spencer Whitney contributed reporting to this story.