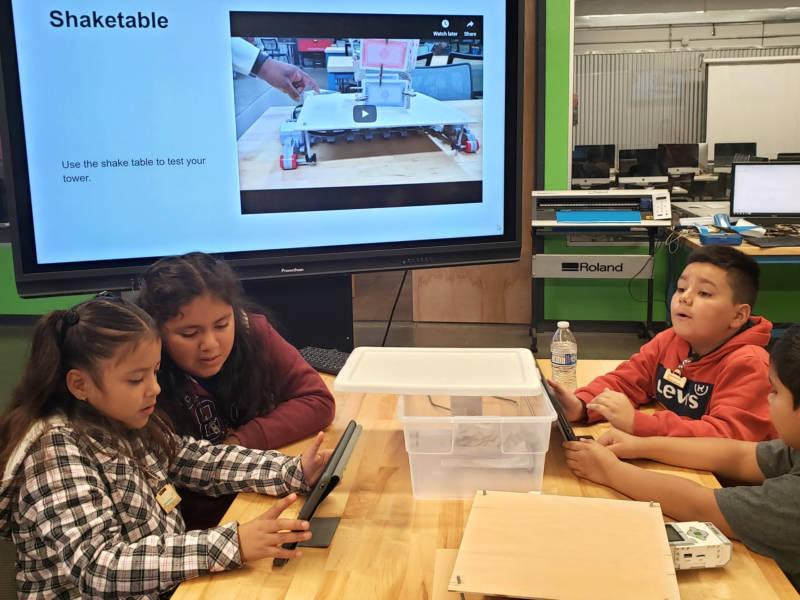

On a recent fall day at the San Joaquin County Office of Education, groups of children built delicate towers out of playing cards balanced on small tabletop earthquake simulators. Their teacher came around and one by one turned on the simulators as the students waited breathlessly to see which tower would stand the tallest after the shaking stopped.

The class is part of the federally funded Migrant Education Program, and the roughly 30 students in attendance were all children of farmworkers. The program offers extra instruction — after school, on weekends and during breaks — to kids who might otherwise fall behind academically as their families move around with the harvest.

“We learn a lot about science and it helps us get ready for [the] school year,” said fifth grader Alexys Chaves, who added that his favorite part was building robots.

But over the past decade, the program has seen a significant drop in enrollment across the state and nationally. Those numbers are reflected in the area centered around Stockton, where the program is run by Manuel Nuñez, a regional director of migrant education.

“When I first started with this region back in ‘01, we had about 21,000,” Nuñez said. “Currently we’re at about 2,200. So that’s a huge drop off.”