W

e all carry some part of 9/11 with us.

There’s raw memory, of course: what we recall about where we were, our experiences that day, the devastation as we saw what unfolded.

And there’s something I’ll call “considered memory”: how we see that experience through the prism of all we’ve lived through, both privately as individuals and as a nation, since that date.

For me, honestly, I’m still puzzling over it. I’ve had an absorbing interest in our history for almost as long as I can remember, since a kids’ Civil War book was put into my hands and I pronounced Potomac as “POT-oh-mack.”

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to understand that one attraction of history, especially the history of war, of conflict, of tragedy, is the recounting of the battle and the exploit in much the same way the epic-singers of old traveled from court to court to relate “The Iliad.” The battle and the exploit, the courage or failure of courage, themselves become the moral of the tale.

Often the recounting goes no further. The Light Brigade is forever charging the guns, always fulfilling a tragic destiny. But what then? What happens after Pickett’s Charge is broken, after Appomattox, after the arms are stacked and the banners furled? What happens when we move beyond the sepia-tinted memories, the strains of elegiac strings, into the life that follows the battle?

The “what then?” is what I think about. To the extent I’m thinking about what Sept. 11 means, that’s what’s on my mind.

M

y brother John and his family lived in Brooklyn, a little more than 2 miles southeast of the World Trade Center, on Sept. 11, 2001. The attacks and their aftermath, things heard and seen, were intimate and immediate.

John’s wife, Dawn, was just emerging from the subway when a jet screamed low overhead and vanished, followed by the sound of an explosion. Looking south from the corner, she could see the World Trade Center’s North Tower had been hit.

John was at work in Brooklyn and watched from a rooftop as a second jet roared across the harbor and struck the South Tower. On the street below, New York Fire Department units sped toward the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel to respond to the disaster across the river.

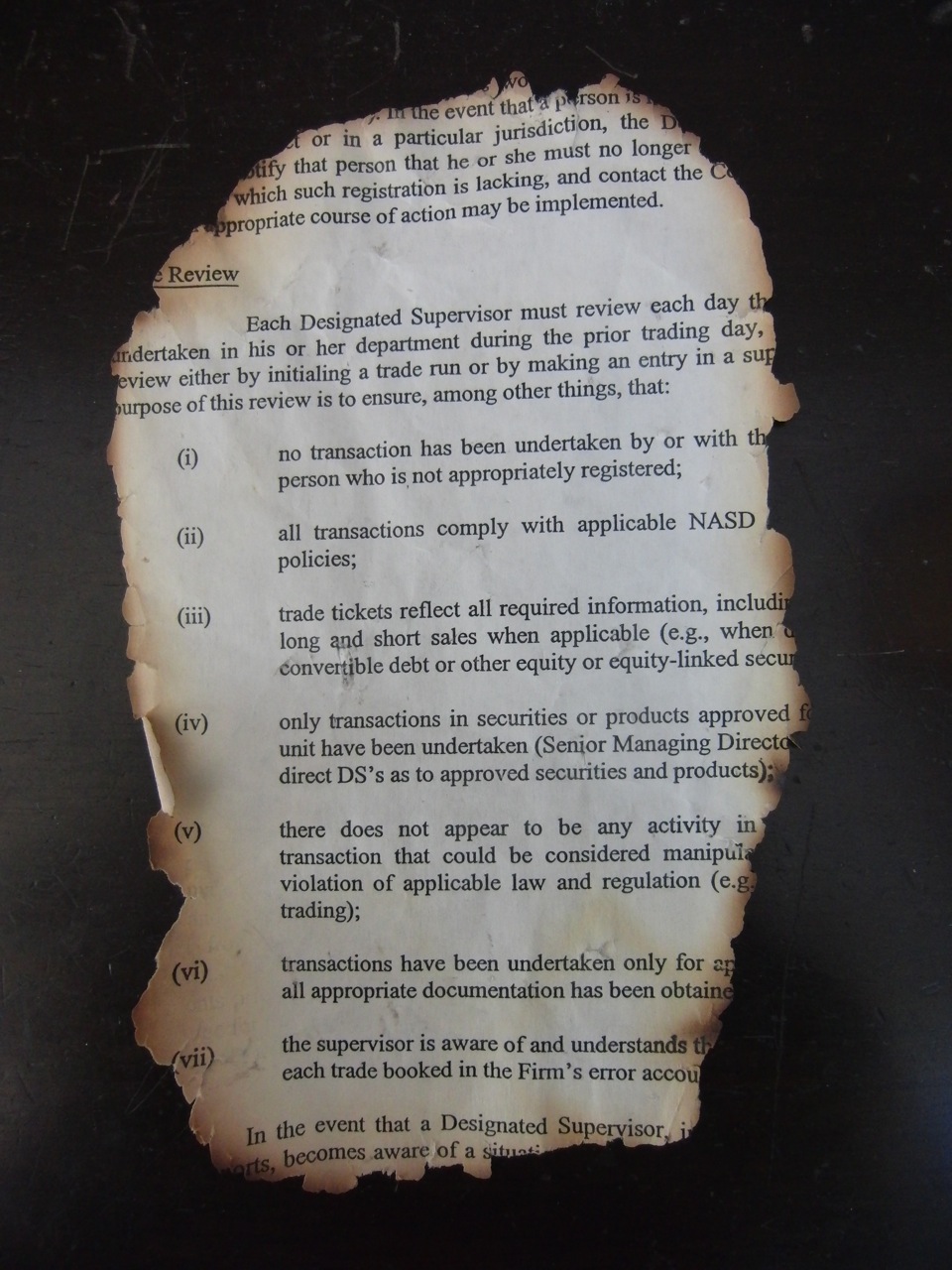

John and Dawn’s neighborhood was downwind from the towers, and the blizzard of dust and paper unleashed when the buildings collapsed scattered scraps, documents and calendar pages everywhere. John told me later he would go around in the weeks after the attack and fill up sacks with the paper that had drifted to earth. At one point, he sent me a small bag with a few of the items he’d found.

I puzzle over these fragments. They’re mundane: part of a financial firm’s rules for handling trades. A blank visitor log for a government office. Design drawings for airport terminal signage. A page from a desk calendar (the date happens to be my birthday).

There’s not a human mark on those scraps of paper. But they were handled by someone, somewhere, in a place we all saw destroyed. Touching them is like touching that place, touching that destruction, touching those who were lost.