Theme music

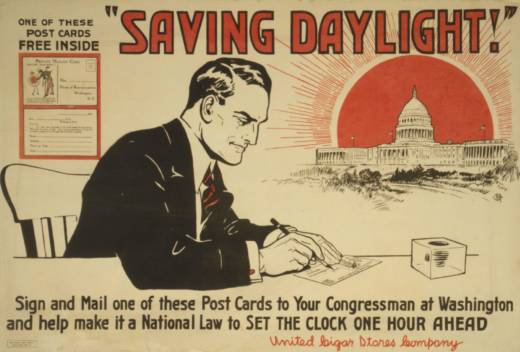

DANIELLE VENTON: Daylight saving time is this practice that we have of switching our clocks twice a year.

ALLEN-PRICE: To help us understand Proposition 7, I called my friend from a few desks down.

VENTON: I’m Danielle Venton. I’m one of the editors on the science desk here at KQED.

ALLEN-PRICE: Prop 7 could lead to the end of switching clocks in California. But before we get into how the prop works, let’s first understand how daylight saving time came to be a thing in the first place.

VENTON: It was an idea that has been kicked around for centuries. Benjamin Franklin, he calculated that the French could save some number of pounds of candles every year by switching their clocks. But the first country to institute it was Germany during the First World War. Then they brought it back for the Second World War and that was meant to save energy.

VENTON: It was voted on by California voters in 1949 to adopt the practice of daylight saving time. It was wartime and this belief that it would save energy and would help the war effort… it was a very popular notion.

ALLEN-PRICE: I’d always heard it had something to do with farms. Is that just a total myth? Is that not true?

VENTON: It seems to be largely a myth. I mean farmers are going to wake up when the sun gets up. Cows do not read clocks. You know, you bail your hay when it’s ready.

ALLEN-PRICE: Because Californians voted daylight saving time into practice in 1949, it’s up to us to vote it out… or, in the case of prop 7, vote to pass control onto the legislature.

VENTON: So if it passes, the state legislature will have the authority to vote on changing daylight saving time, and if they approve it by two thirds, and if the federal government allows, then California could maintain year round daylight saving time.

ALLEN-PRICE: So people can think of this as like step one in, at least, a three step process.

VENTON: Right. But it’s likely that if there is a lot of voter support for this then the legislature would follow the will of the people.

ALLEN-PRICE: How did this get on the ballot?

VENTON: So Assembly Member Kansen Chu…

KANSEN CHU: Kansen Chu. I’m a state assembly member representing District 25.

VENTON: From the South Bay heard about this issue from one of his constituents.

KANSEN CHU: I got this idea from my dentist. You know he was telling me there was a health impact.

MALE NEWS ANCHOR: New at Six. Potential daylight saving time dangers. Now that the sun sets later.

FEMALE NEWS ANCHOR: But the changing of the clocks can also disturb sleep. Something some experts blame for an increase in car crashes this time of year.

VENTON: There is consensus that it disrupts sleep schedules, that there’s a higher incidence of heart attacks and stroke.

ALLEN-PRICE: Supporters of Prop 7 say not only is daylight saving time hazardous for your health, but it doesn’t really save energy either. Studies have found that energy savings is pretty much a wash. On the other side of the coin you’ve got opponents of Prop 7 who say darker mornings could be dangerous for pedestrians.

VENTON: If we kept daylight saving time year round that would mean very dark mornings in the winter, some people worry that that puts children, in particular, at extra risk when they are traveling to school.

ALLEN-PRICE: Now California wouldn’t be the first place to try to ditch the clock switch. Arizona and Hawaii don’t do daylight saving time and neither do most countries in the world. Even if this prop does pass, things aren’t going to change overnight.

VENTON: Clocks would still change in November, of course, on November 2nd. And they would still change in the springtime. But the legislature would have the choice of keeping that change permanent.

ALLEN-PRICE: So potentially in a year, we would not be falling back?

VENTON: That’s right.

ALLEN-PRICE: Next we turn to proposition 12, the animal confinement prop. It was put on the ballot by the Humane Society of the United States. KQED Science reporter Lesley McClurg explains what it’s all about.

LESLEY MCCLURG: Californians are going to vote on whether or not animals should come out of cages, like, altogether. So it would take pigs, egg-laying hens and veal calves out of cages altogether, and it allocates a specific amount of space for each animal depending on which animal it is.

ALLEN-PRICE: Now there are some farms that are basically already doing this kind of farming, right?

VENTON: Yeah, exactly. I went to a small farm in Pescadero near the coast and a farmer there, her name is Dede Boies, showed me around the grounds. And she is really, really passionate about taking care of her animals in the most natural conditions that she can.

DEDE BOIES: So we pasture raise two different breeds of slow-growing chickens, and ducks, heritage turkeys and pigs. Right now we’re kind of looking at the set up we have, where all the animals get rotated.

MCCLURG: The animals are kept in a very large, very open space.

DEDE BOIES: This time of day, they’re pretty much in the shelter. But in the morning and evening they definitely spread out a lot more.

MCCLURG: And she’s just really against the idea of keeping animals confined in any way.

DEDE BOIES: The point for me is to raise animals in a way that they were intended to live.

ALLEN-PRICE: Dede Boies supports Prop 12 because she wants to see more animals raised without cages. If this prop feels vaguely familiar to you, there’s a reason why.

ALLEN-PRICE: Didn’t we already do this? I remember voting on this already.

MCCLURG: In some ways we did already. This was Proposition 2, back in 2008. It said that animals should have enough space to stand up, sit down, turn around and spread their limbs or wings. It didn’t allocate a specific amount of space, and industry basically argued that that was too vague, so they didn’t take the animals out of the cages, they just put fewer animals in the cages.

ALLEN-PRICE: So, is it fair to think of Prop 12 as kind of a redo of Prop 2? Only this time, like, with much more specific requirements?

MCCLURG: Yeah that’s right. And so it’s 43 square feet per calf. It’s 24 square feet per pig and each egg-laying hen will have to have a foot of space. I think what’s important about Proposition 12 is it not only includes animals in California and how they’re raised but also anything imported into California. So this will change the practices for producers all across the country.

ALLEN-PRICE: And as you might guess, not all those producers are thrilled about Proposition 12.

MCCLURG: I also talked to a guy named Ken Maschhoff. He’s a pork producer in Illinois.

KEN MASCHHOFF: We’re on the same land that my great great great great grandfather purchased in 1851.

MCCLURG: And he was really adamant that he believes in taking care of animals, but he actually specifically said the animals do not have rights.

KEN MASCHHOFF: But I believe that farmers, ranchers, veterinarians are animal welfarists. So there’s a difference between animal rights and animal welfare.

MCCLURG: And then we should take care of animals as best we can but we need to be cost effective.

KEN MASCHHOFF: [This] type of legislation actually affects low income people much much harder than middle or high income folks because they just can’t afford the cost of their food.

MCCLURG: And he says, you know, if consumers are willing to pay more these products are already available in the grocery store. You can already buy cage-free, organic, etc. products. Those are available. So why force everyone to do something that maybe they can’t afford?

ALLEN-PRICE: If Prop 12 passes there is some time built in for producers to adapt their facilities. Changes for pork and veal need to be done by 2020 and for egg-laying hens, it’s 2022.

ALLEN-PRICE: Last up, we’ve got Proposition 3. And what would a California election be without a water prop on the ballot? Voters just okayed a $4 billion water bond in June of this year. And here we are again.

FEMALE NEWS ANCHOR: A measure on the ballot this November could have major implications for our water here…

FEMALE NEWS ANCHOR: …Proposition 3 authorizes bonds to fund projects for water supply and quality.

MALE NEWS ANCHOR: It’s an $8.9 billion bond measure for water-related projects.

ALLEN-PRICE: If passed, Prop 3 would issue nearly $9 billion in bonds to fund a bunch of different water projects. The largest payouts go to projects that improve water quality, restore watersheds and help sustain our groundwater. There is some disagreement among environmentalists on this one. Supporters, like Save the Bay, say it will leave the state better prepared for a drought, and help fix our water infrastructure. But opponents, like the Sierra Club, say it benefits wealthy farmers in the Central Valley and taxpayers shouldn’t foot the bill for projects the private sector should cover. We’ve got more on Proposition 3 on the Bay Curious website. You’ll find a KQED Forum debate on the topic, plus a guide to all the propositions on the November ballot.

ALLEN-PRICE: This episode was produced by Ryan Levi, and me, Olivia Allen-Price. We’ll be back in your feed tomorrow morning for a look at Proposition 5, which could expand tax breaks for homeowners 55 and older. It’s a really interesting one. You definitely want to tune in. Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at KQED.