This story is part of the Bay Curious series “A Very Curious Walking Tour of Golden Gate Park.”

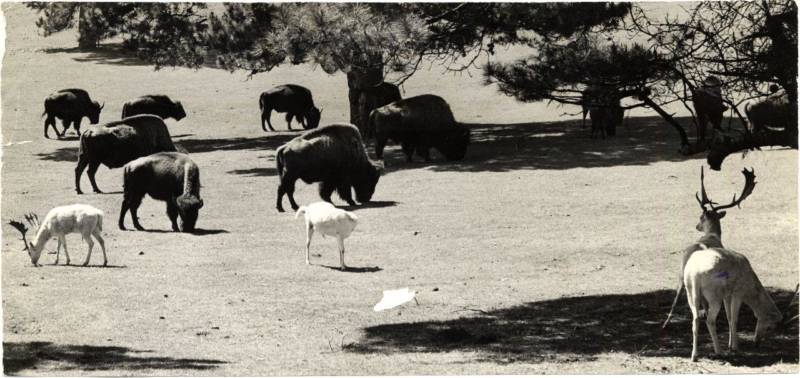

San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park: In our humble opinion, with so many treasures across almost 1,000 acres, it’s arguably one of the best urban parks in the world. There’s a pair of windmills that look like they belong in the Dutch countryside, and through an elaborate gate you’ll find the oldest public Japanese teagarden in the United States. But perhaps the wildest treasure in the park is the herd of American bison.

In March 2020, for the park’s 150th anniversary, a birthday gift of five new bison calves were added to the herd.

Seeing the bison in the park is unexpected, says Bay Curious listener Paul Irving. After all, bison aren’t native to San Francisco, and they certainly stand out in today’s urban setting. After years of cycling past the paddock, Irving asked Bay Curious: “What’s the story behind the bison in Golden Gate Park?”

The answer goes back hundreds of years.

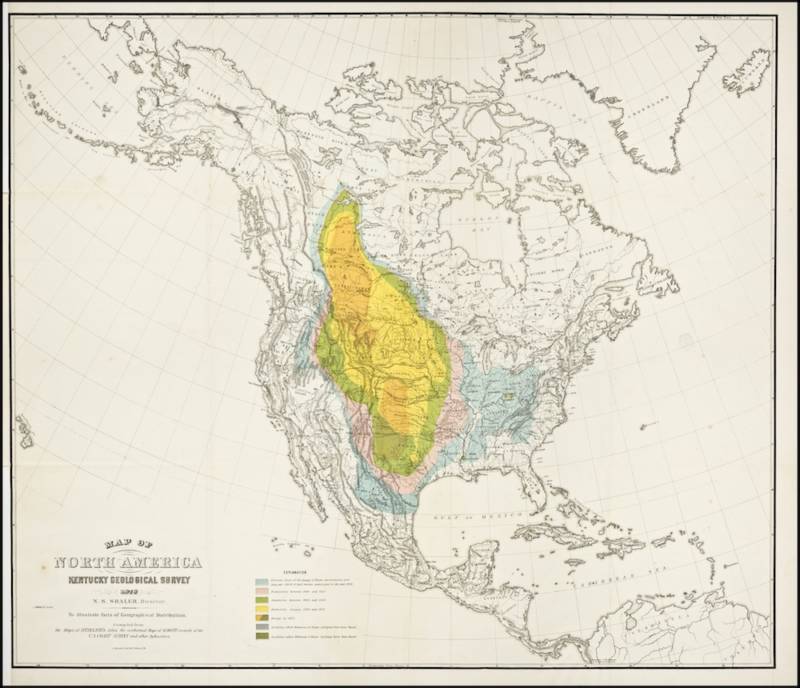

In the 1500s, an estimated 30 million to 60 million bison roamed American prairies. They grazed all over the West, from northern Mexico up through Canada.

As European colonizers moved into the West, the bison’s habitat was chopped up by railroads, or turned into farms. Imported cattle brought grazing competition and new diseases to the bison. But the greatest threat to bison was hunting. Bison meat was exported or eaten on the spot, skins were sent to commercial tanneries, and bones were ground up to make things like fertilizer and bone china.

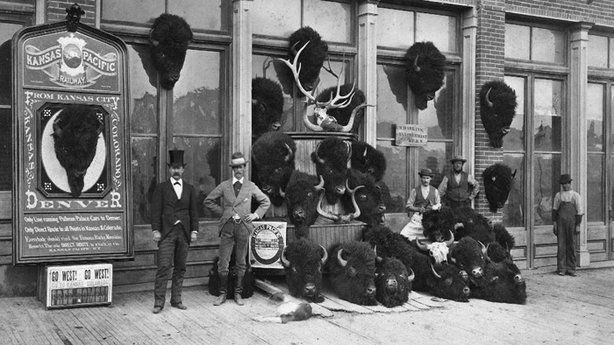

William F. Cody, aka Buffalo Bill, allegedly killed 4,280 bison over 17 months to feed construction crews of the Kansas Pacific Railroad.

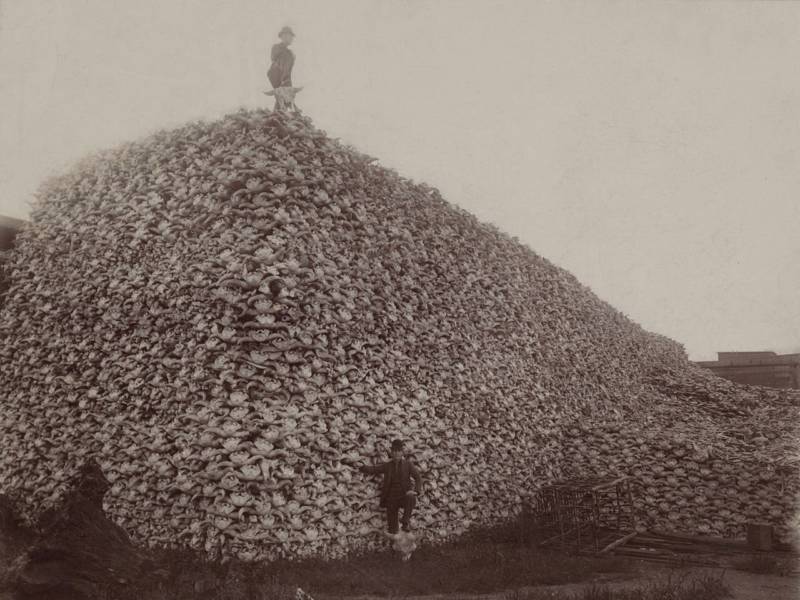

Bison also were killed for sport. Competitions were held to see who could kill the most bison (Buffalo Bill got his nickname at one of these competitions). Tourists on trains would shoot the animals from their seats, leaving the carcasses where they fell. In 1973, a railway engineer in Santa Fe said it was possible to walk 100 miles along the railroad by stepping from one bison carcass to another.

While the U.S. government clashed with Native Americans over land, the army encouraged the rampant slaughter of bison, which were an important native resource. One colonel even said to hunters, “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

By 1889, the estimated number of bison had dwindled to about 1,000.

The bison come to Golden Gate Park

It was around this time that work began on Golden Gate Park.

“When Golden Gate Park was created, the idea was to honor the Wild West,” says Phil Ginsburg, general manager of San Francisco Recreation and Parks.

To recreate the Wild West, the park needed bison.

The first bison was brought to the park in 1891. It was soon joined by more bison from private and public herds.

“Bison and several other animals were actually first put in a paddock, which is very close to where Kezar Stadium is today,” Ginsburg says.

The zoo had a captive-breeding program that produced more than 100 bison calves, though the program has since ended.

Over the decades, conservation efforts (and, ironically, an increased interest in bison meat) have brought the North American bison population back into the hundreds of thousands.

Today’s herd

The bison currently living in the pen in Golden Gate Park are not descended from the original animals brought to the park. The bison were replaced by a younger herd in 1984 and again in 2011. At the beginning of March 2020, the five new bison calves were added to the surviving 2011 herd.

Today, all the bison in the paddock are female.

“Having all females just keeps everything a little bit more calm,” says Ginsburg.

When there were bulls, the bison could get aggressive. One tried to maul a police officer on horseback, and another tried to escape by running into the Sunset District.

“Males become very aggressive around August because they’re fighting for dominance in order to breed with the females,” says Sarah King of the San Francisco Zoo, which takes care of the animals. “Then calves are generally born in the spring, nine months later, and that’s when the females get aggressive because they’re very protective of their offspring.”

Though they may appear to be slow, bison are powerful creatures. They can run over 30 mph, jump up to 6 feet in the air, and swim over half a mile, says King.

These days the paddock is calm. On any given day, you can see the bison either grazing or resting. Most of the excitement in the paddock is human-generated. For example: The streaker who was arrested for running into the paddock during Bay to Breakers.

A version of this article was first published on June 8, 2017. In the last few years some bison referenced in the original story have passed away.