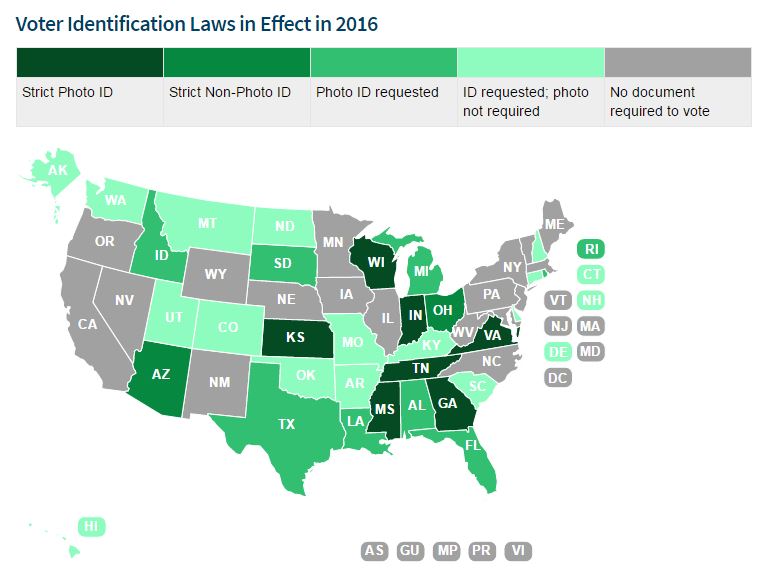

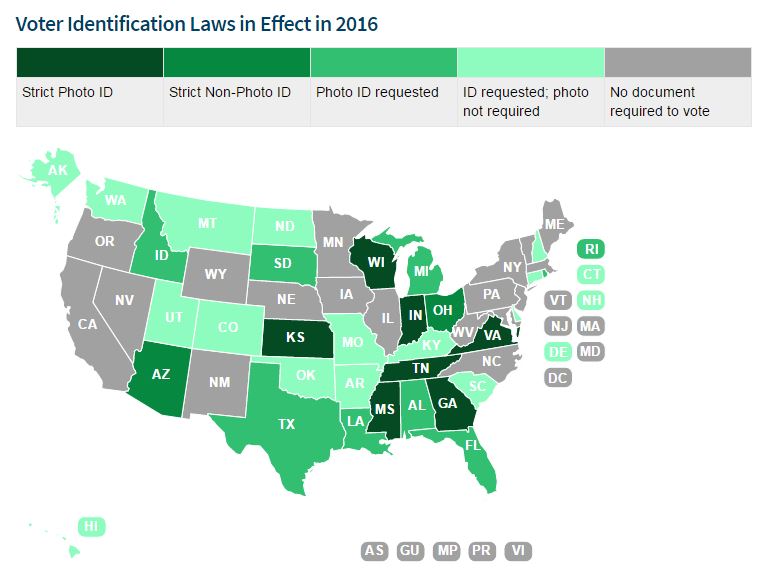

32 states currently require voters to show some form of identification at the polls, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Seven of them have strict voter ID requirements.

Roughly 11 percent of eligible voters don't have government-issued photo IDs, according to the Brennan Center.

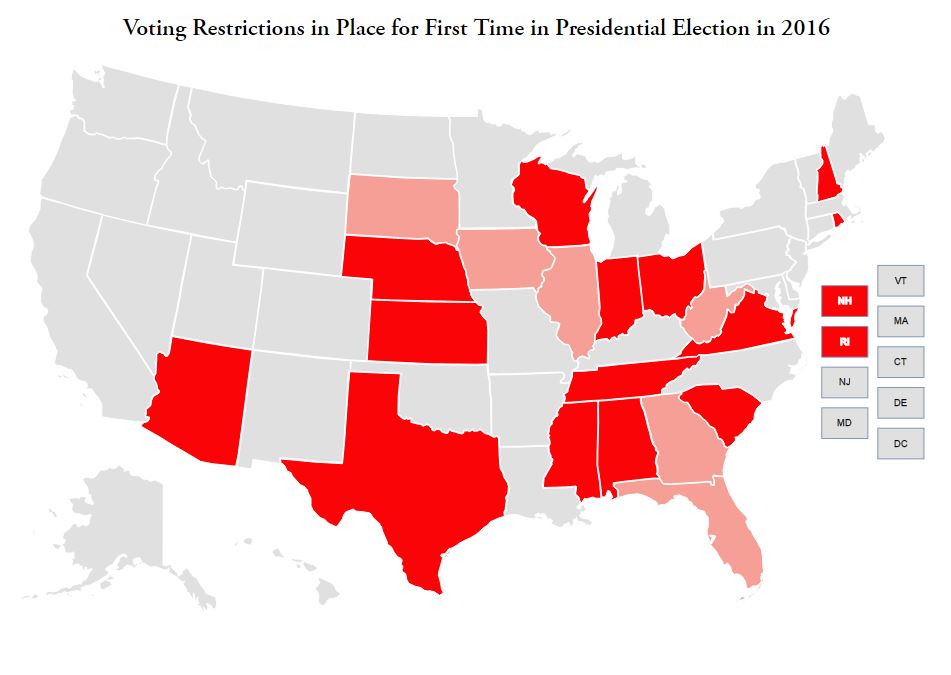

North Carolina's 2013 voter ID law was recently struck down by a federal appeals court, which found that the law was intentionally aimed at the black vote. Two separate court rulings this summer scaled back new voting restrictions in Texas and Wisconsin.

Voting rights advocates argue that stricter voting laws disproportionately suppress turnout among students, African-Americans and low-income voters, groups that traditionally lean Democratic.

Most new voting laws haven't been in place long enough to accurately measure their impact on participation. But several studies predict that these laws could thwart hundreds of thousands of otherwise eligible voters from voting. In one recent study, political scientists at the University of California, San Diego compared voter turnout from 2008 to 2012 in states that did and did not implement strict voter ID laws. In states that began enforcing these laws, voter participation decreased markedly, particularly among blacks, Hispanics and mixed-race groups.

Proponents of stricter laws counter that voter fraud remains a serious threat that needs to be addressed.

"Our Republic flourishes when citizens are confident that their vote is free, fair, and secure," notes Catherine Engelbrecht, founder of the advocacy group True the Vote. But concern over election fraud, she adds "jeopardizes our entire system of government, eroding our trust in elected leaders and undermining our confidence in the system by which they govern - beginning at the polls and rising up through the highest offices in the land."

But even though a majority of Americans favor voter ID requirements numerous non-partisan studies of voting records show that voter fraud is exceptionally rare and statistically insignificant.

In one recent investigation, Loyola Law School professor Justin Levitt found only 31 credible incidents of voter impersonation out of a sample of more than 1 billion votes cast.

"It's really not one America when it comes to voting," Judith Brown-Dianis of the Advancement Project explains in the documentary Electoral Dysfunction.

In fact, the text of the original Constitution doesn't actually include a single mention of voting rights; the founders left this to the discretion of states. Only subsequent amendments (namely, the 15th, 19th, 23rd and 26th) prevent voting rights from being denied to certain formerly disenfranchised populations (people of color, women, 18 to 20-year-olds). States, though, remain largely free to determine their own voting procedures.

"The Constitution, at the nation's birth, made no mention of voting rights whatsoever," Harvard University History Professor Alex Keyssar notes in the documentary. "[The Founders] were unsure, in fact, whether voting was a right or a privilege. And if it was a right, they weren't sure who the right actually belonged to."

It's an ambiguity that continues to play out today: voting laws vary drastically from one state to the next, helping to determine who's allowed to participate and who gets stuck watching from the sidelines.

Additional resources

Links to official election resources for all 50 states

Brennan Center: state-by-state student voting guide

Electoral Dysfunction (film) educator resources

True the Vote (advocates for stricter protections against voter fraud)

ProPublica: Everything that's happened since the Supreme Court's Voting Rights Act decision

The new voting laws have been mostly instituted in states with Republican-led legislatures, with the ostensible intention of reducing voter fraud. The changes, which snowballed after a 2013 Supreme Court ruling scaling back the Voting Rights Act, range from photo ID requirements and felon voting restrictions to shorter registration windows and limited early voting periods.

The new voting laws have been mostly instituted in states with Republican-led legislatures, with the ostensible intention of reducing voter fraud. The changes, which snowballed after a 2013 Supreme Court ruling scaling back the Voting Rights Act, range from photo ID requirements and felon voting restrictions to shorter registration windows and limited early voting periods.