You know that old stereotype about Victorians being genteel and of restrained dispositions? Lies. All lies. Turns out that nothing got these cats more excited than blowing stuff up.

Victorians Sure Liked Blowing Up Islands in the Bay Back in the Day

Let’s not forget that in 1896, Golden Gate Park horticulturalist John McLaren decided that exploding Bonet’s Electric Tower into a gazillion pieces would be way more fun than the city having its very own Eiffel Tower forever. Then there’s the mortifying fact that much of the destruction from the 1906 earthquake was caused by the doofuses who decided that dynamiting the streets was the best way to stop the spread of fire. (Obviously the situation was desperate but come on, people…)

Make no mistake: If ever there was an excuse to make something explode, humans at the turn of the century damn well used it. And once these maniacs set their sights on the Bay waters, a series of islands minding their own business providing perches for seagulls and whatnot just didn’t stand a chance. Considering them obstructions that posed a danger to passing ships, the Victorians quickly concluded that dramatically obliterating them into airborne shrapnel was the best possible solution.

What’s more, we know — thanks to some extremely diligent and detailed reporting at the time — that the relish everyone in the region took in all that wanton destruction was immense. Please now journey back with us as we examine just how much this unhinged generation of people enjoyed blowing crap up.

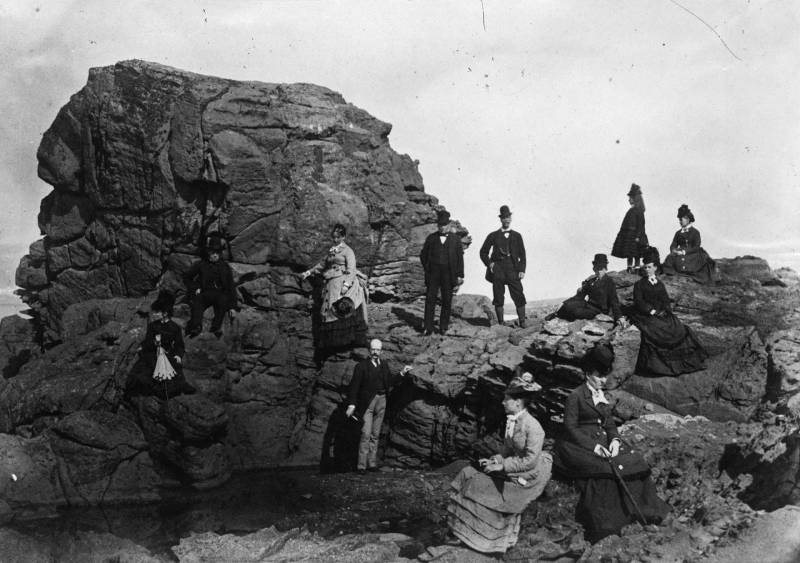

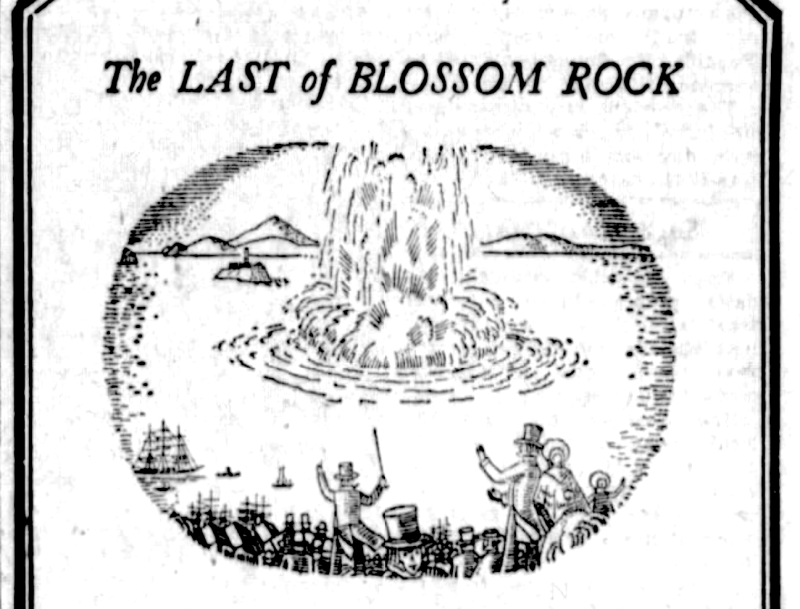

Blossom Rock

When Blossom Rock got blown to pieces by Colonel A. W. von Schmidt in 1870, the city of San Francisco collectively lost its damn mind. The San Francisco Examiner later reported:

For days and weeks the public was in a state of expectancy, and when the moment arrived, excitement was keyed up to the highest pitch. The occasion was made a holiday in the city. The entire town seemed to be on the bay or at the water front. Telegraph Hill never before held such a crowd. A big crowd scrambled on to the roof of an observatory and the roof collapsed, resulting in injuries to many. Out on the bay, everything that could get up steam or rig a sail and hold together was pressed into service, and all the craft was crowded with excursionists.

It wasn’t just the public that approached the end of Blossom Rock with zeal. Colonel von Schmidt went so hard, one can’t help but wonder if he had personal business with the outcrop. The San Francisco local had managed to win the contract to destroy Blossom Rock after coming up with a budget that was a quarter of the projected cost. Then he went about hollowing out the rock and jamming it full of explosives.

The column of water and debris that shot up after the island was detonated was 300 feet high and prompted the gathered, over-excited crowds to cheer with delight.

Psychopaths, one and all.

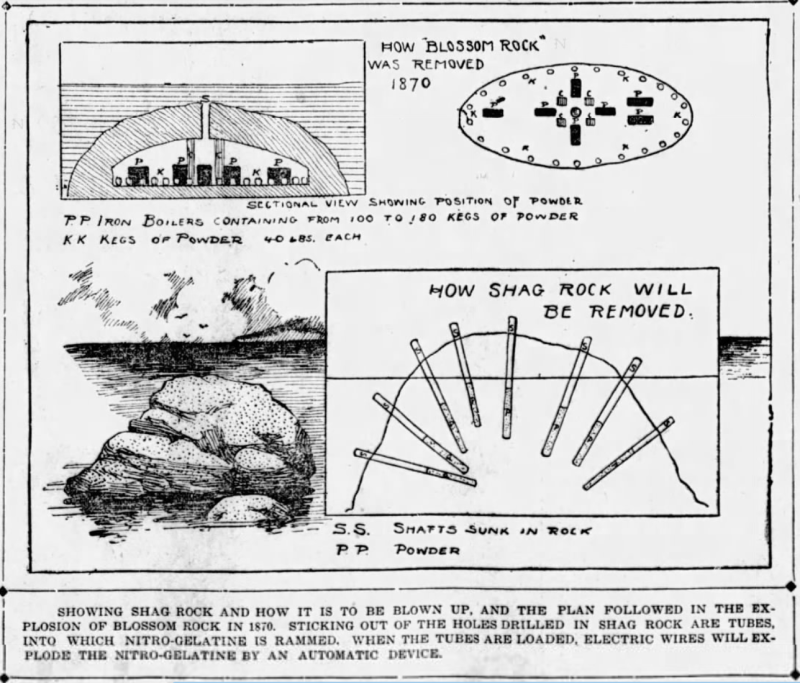

Shag Rock

Though very much appreciated by everyone who witnessed its destruction, the end of Blossom Rock was positively quaint compared to what happened to Shag Rock.

The 2,192-square-foot island met its end just after 3 p.m. on April 30, 1900, and the resulting explosion shot up 981 feet into the air. The San Francisco Call described it as “one of the most beautiful and impressive sights ever seen on the bay of San Francisco,” and went on:

In the twinkling of an eye, a huge mass of rock and water and splintered lumber … were flying heavenward. Long before the water had ceased mounting upward, the rock was falling back into the water and the splash, splash, splash of the huge pieces could be heard a mile away … The water over the spot once marked by Shag Rock continued its boil for nearly 15 minutes.

Thousands of spectators on Alcatraz, Angel Island, Telegraph and Russian Hills and at the Presidio marveled at the sight, and around 100 boats sailed out to see what was left of Shag Rock. “They witnessed one of the grandest sights ever seen on the bay of San Francisco,” The Call reported the following day.

Within days, people had already started to wonder if Shag Rock was blown up enough. “Nearly all the rock that got blown into the air fell back into the hole again and this has now to be removed,” one Call reporter wrote on May 4, 1900. “If divers and dredgers cannot do the work, then torpedoes will be used.”

These people were bonkers.

Shag Rock No. 2

The first Shag Rock had been considered a major shipping hazard, but No. 2, located half a mile north of Alcatraz, was almost more hated because the 1,863-square-foot rectangle of rock lay entirely underwater.

Once the first Shag Rock (150 feet from where No. 2 was) had gone, No. 2 was even easier to hit by boat, making it all the more treacherous. Within six months, the sandstone, quartz and basalt structure had, rather unsurprisingly, been annihilated by whooping Victorians. And this time, the explosion — made by 10 tons of nitro-gelatin spread across 150 charges — made it all the way up to 1,106 feet.

The San Francisco Examiner described the sight thusly: “From an artistic standpoint, the blowing up of Shag rock No. 2 was a perfect success.”

The Chronicle called it “one of the grandest spectacles ever witnessed in this part of the world,” and noted:

Impressive as was … the blowing up of Shag Rock … could not be compared in majestic beauty with yesterday’s display. Not only did the amount of explosive materials used yesterday exceed by an entire ton the quantity used in leveling the first rock, but the column of water which shot upward from the depths was unspotted by the earthen crust of the shattered rock and for several seconds after reaching its greatest height shone splendidly in the bright sun like a gigantic marble column.

Newspapers also happily reported on all the fish murdered by the explosion. Waiting fishermen rushed in afterwards to retrieve cod, perch, sardines and one 45-pound sea bass. Waste not want not, I guess?

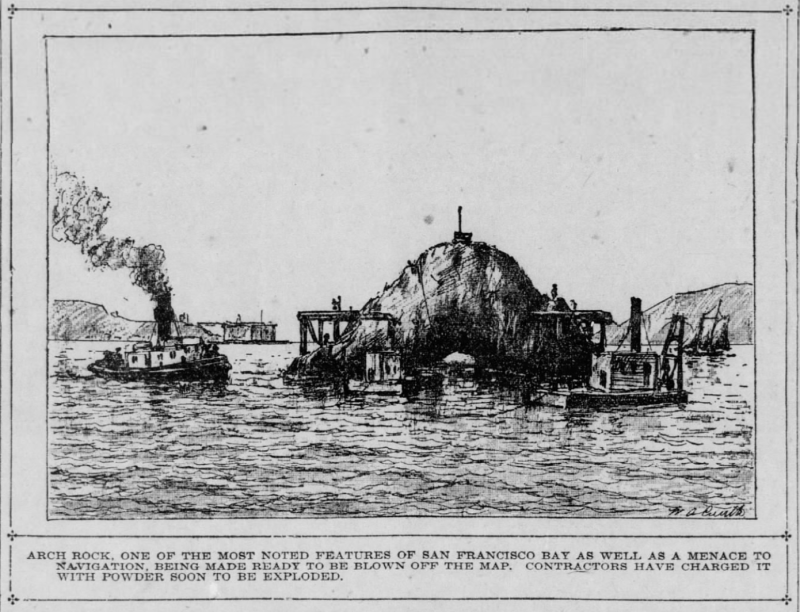

Arch Rock

The destruction of the 30-foot-high Arch Rock was at least a little controversial. Sausalito and Tiburon residents were most attached to the picturesque rock formation and begged local authorities to attach a beacon light to the land to make it safer, rather than removing it altogether. Predictably, those in charge opted for a solution involving 35 tons of gelatin packed into 250 charges instead. But not before the man responsible for that handiwork, Robert Axman, had allowed some ladies onto the explosives-laden rock formation to play with the charges.

On Aug. 16, 1901, The San Francisco Examiner reported:

Twenty-five members of the Technical Society of the Pacific Coast, civil mechanical and mining engineers, accompanied by the ladies of their families, visited Arch Rock yesterday morning on a tug as the guests of Robert Axman … The ladies stuck their fingers into this mountain-moving explosive yesterday afternoon. They probed and poked when the man in charge told them that it would not go off unless severely kicked. It comes in a black tar-coated package the size of a stove pipe and quivers to the touch like new cheese.

Nothing to see here!

Shortly afterwards, Axman had his daughter Florence detonate the explosives using “a tiny knob” on a barge that floated 4,000 feet away from the Arch. The public started gathering to watch a full two hours before the island was destroyed.

On Aug. 16, 1901, The San Francisco Call provided an elaborate description of the bomb:

With a low rumble and a sharp subsequent explosion this landmark of the northern bay flew helter-skelter into space … The emulsion of sea water towered aloft and hung like a grim, huge specter over the scene of destruction. It remained long enough for the sun to play upon it and produce glimmering, scintillating light effects … Timbers, rock and sea water beat into a foam spread for a half-mile around the one-time jutting rock. A small-sized tidal wave was kicked up.

A month later, the same newspaper made another, rather bleaker, observation. “All the shags and sea fowl that used to congregate on Shag and Arch rocks have disappeared since the work of destruction began. Seafaring men are now wondering what new abode they have found.”

Imagine that.