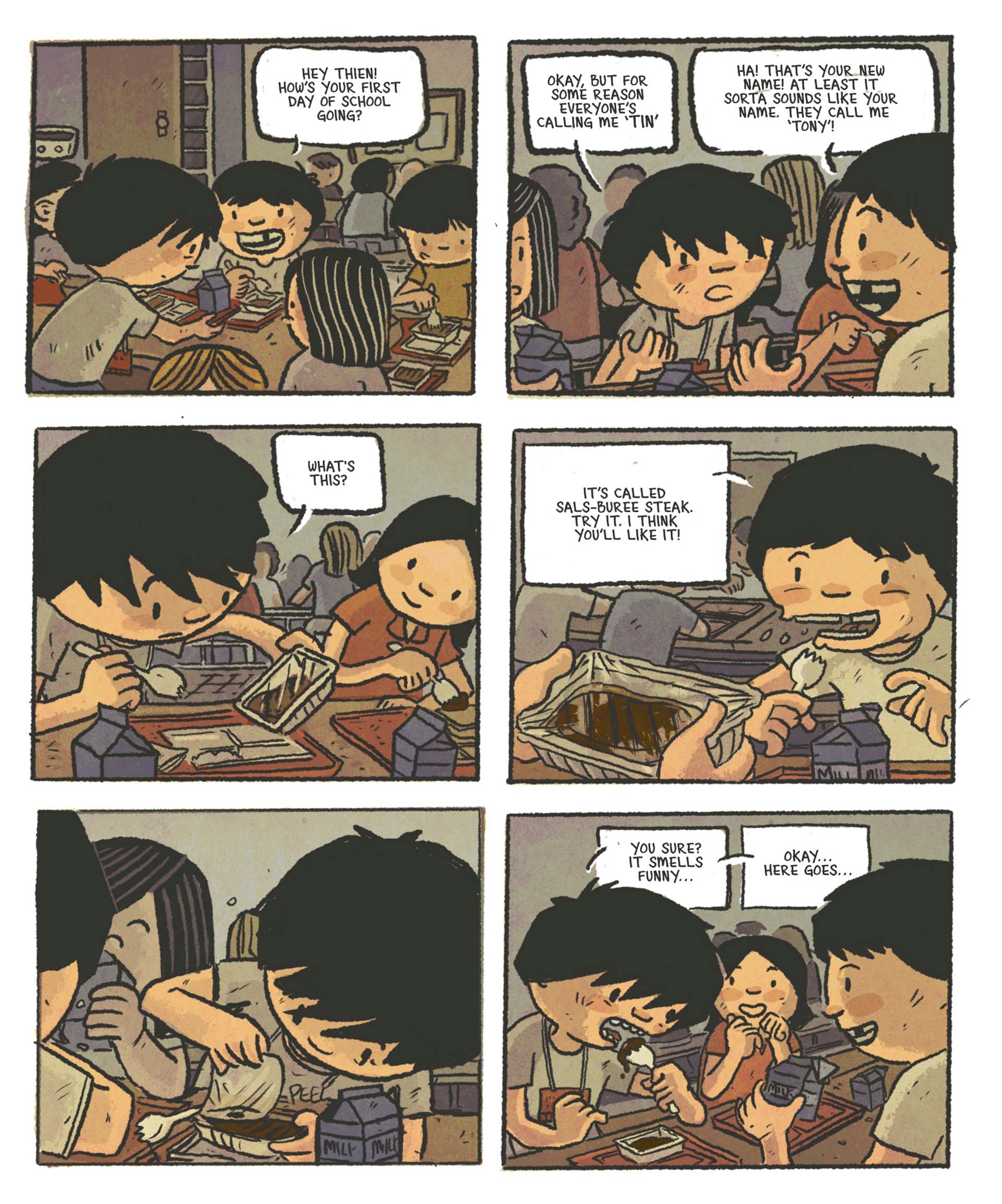

There’s one poignant scene when Pham eats his first bag of potato chips with his family after they’ve worked as migrant field laborers picking strawberries. Later as an adult, he memorizes important dates in U.S. history in order to pass his citizenship test while eating lunch in the teacher’s lounge. Often, food is at the center of it all, helping to nourish Pham’s identity and feed his family’s aspirational immigrant dreams.

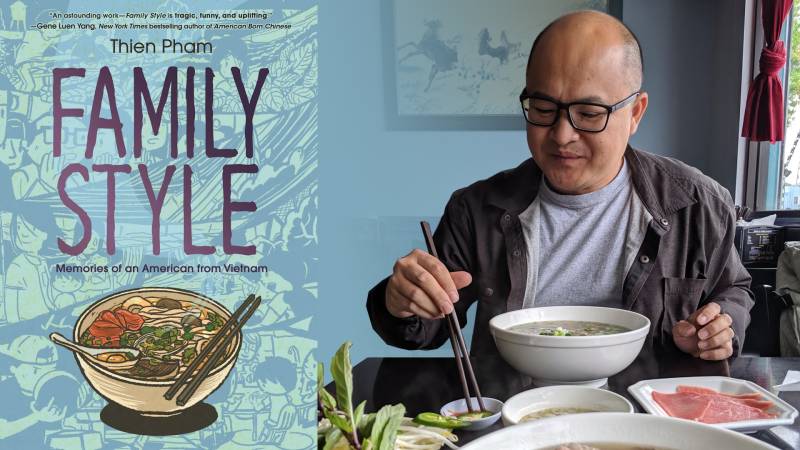

On the eve of his national book launch, I spoke with Pham about his memories of growing up in the Bay Area, his favorite San Jose restaurant and the beauty of being an immigrant.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

********

Alan Chazaro: Family Style is a graphic novel about food, family, diaspora, teenage angst, American assimilation and more. As a visual storyteller, where did you begin, and how long did it take to complete?

Thien Pham: I’ve wanted to tell this family story for a long time, but there were things preventing me from it in the past. I never had a tight enough connection with my parents to get the full story, my art style wasn’t where I wanted it to be and I didn’t have a fresh enough perspective. Coming to America as a Vietnamese immigrant has been told before. It’s a universal immigration story, and I didn’t know how to tell it at the level I thought it could be. I needed time to figure it all out.

During the pandemic, it just intersected for me in a weird way. I finally spent time with my parents and talked to them about it all, and we were all old enough to talk about the truth. I also felt at that point my art was at a level that could do the story justice. When I talked to my mom, I realized that what I told her was mostly food related. As soon as I got that last piece, I knew that was the angle for me to approach it: immigration told through food. It was the missing piece; it was already inside me.

After that, I just did it page by page. It was fast, in terms of drawing comics; it wasn’t agonizing or dragged out. It’s not often I get that. Maybe two or three times in my life I’ve had that feeling. That’s one of the reasons this book is so special to me. Who knows if I’ll ever have all that coming together so perfectly again? At the end of the book, there are strips of me talking to my parents and explaining how the book was created. I wanted to capture that in the book. It was magical.

Your first graphic novel, Sumo, was published over a decade ago. When did you realize you were ready to illustrate and write Family Style?

Everybody has stories in them, but it’s about recognizing when it’s time to share it. That’s crucial. I didn’t have any idea about my next big graphic novel. I would start and stop with things and nothing really stuck. I can only create when I feel a major emotional pull to do it. But between those graphic novels I’ve been drawing. I did short stories, food magazines. I was always honing my craft. Through these smaller projects I really found how to tell stories in my own voice. By the time the inspiration finally hit me, I was ready in terms of art and storytelling. I was at the point I could tell the story in the style I wanted.

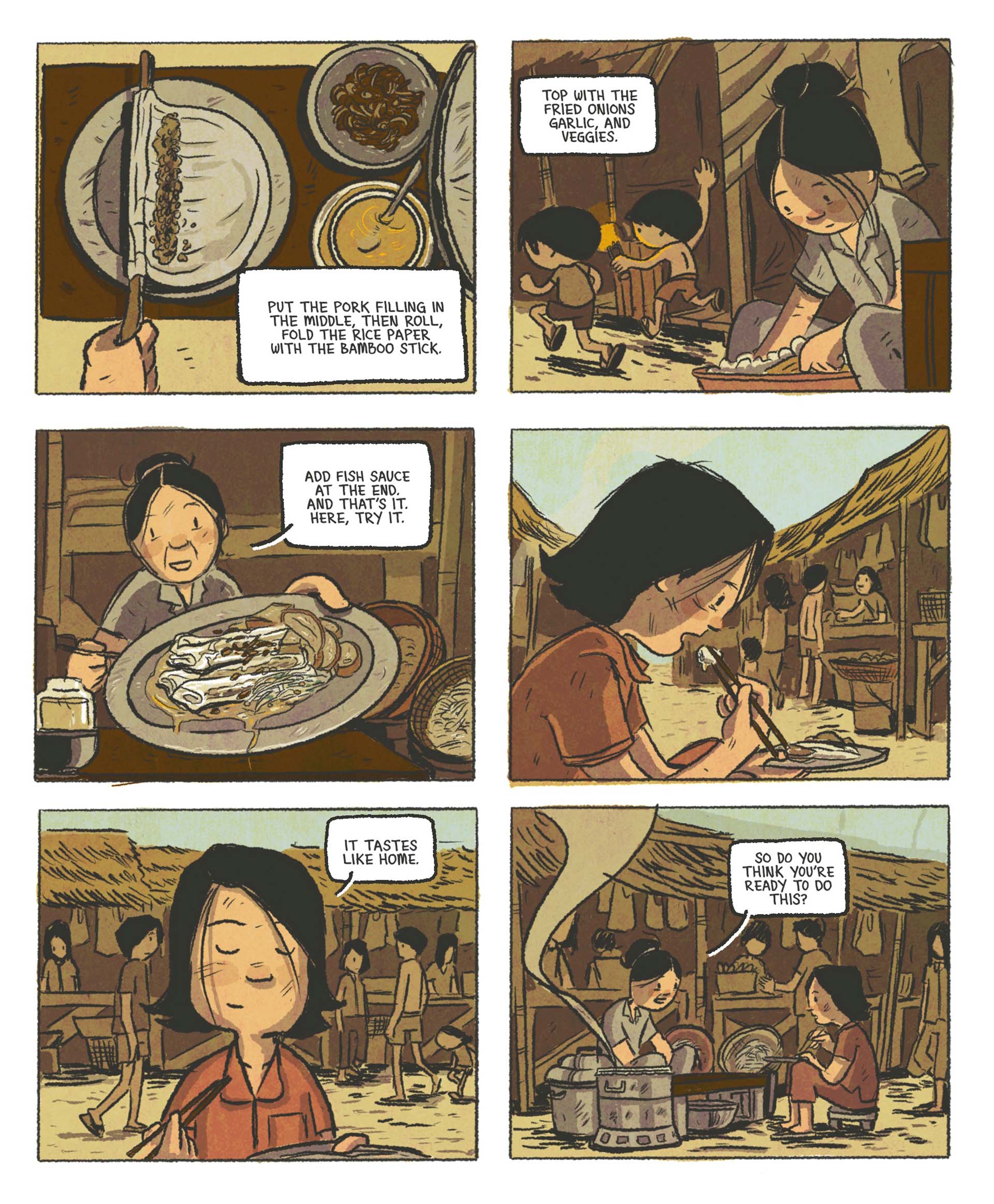

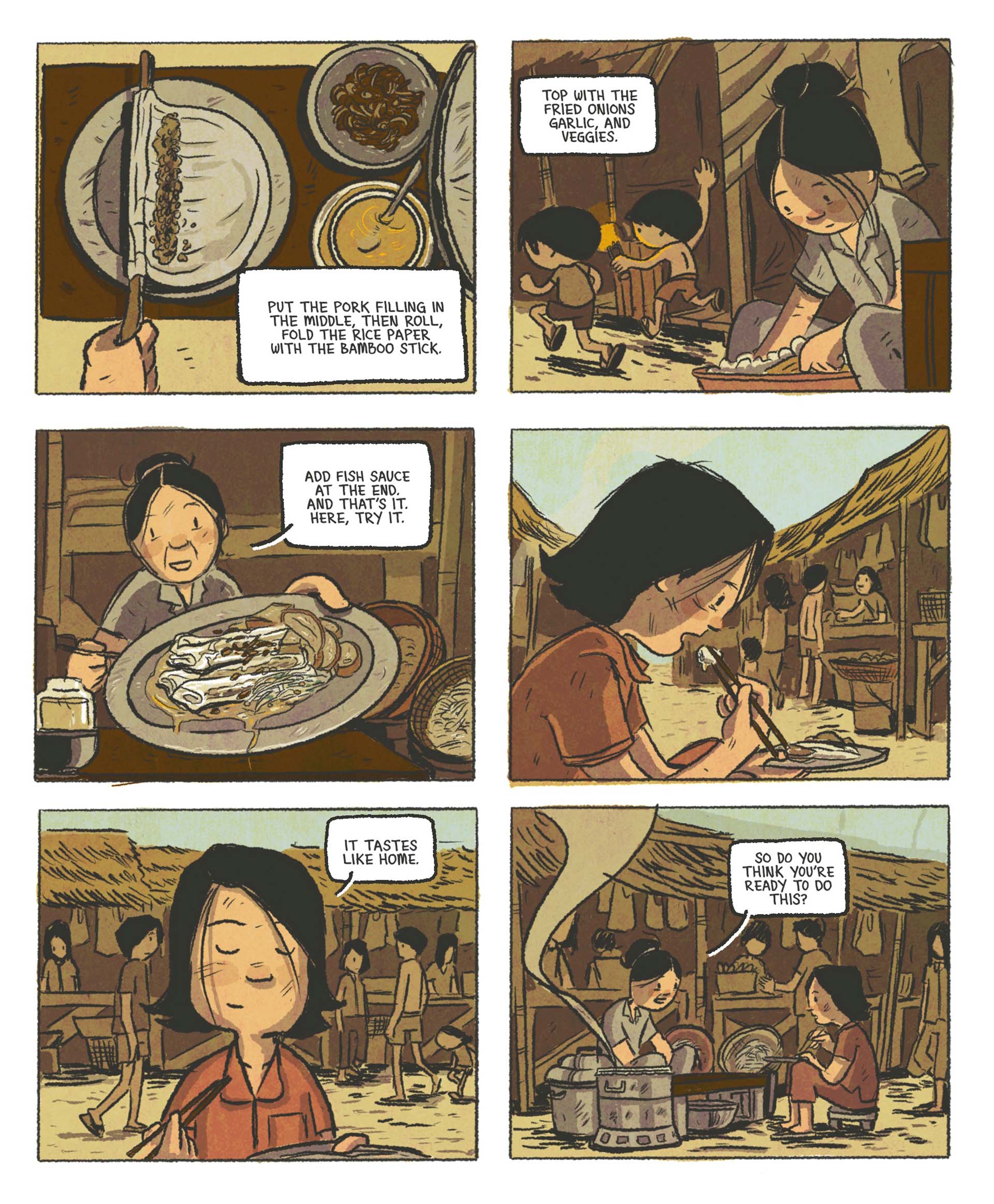

The book includes references to recipes related to your family’s experiences. What have you realized about the connection between food and family?

I always wanted to cook my mom’s food. I missed it. During the pandemic, you couldn’t just go to Vietnamese restaurants, so I started learning how to do it. Every day I tried to make something my mom made me when I was a kid. This is a very metaphoric thing in the book. I thought these simple meals she used to make were easy and took no time, and they were delicious. She made meals in 15 minutes for the family in between her work shifts. But when she described to me how they were made, I realized simple meals are very, very nuanced, and there are so many more things to it I never thought about.

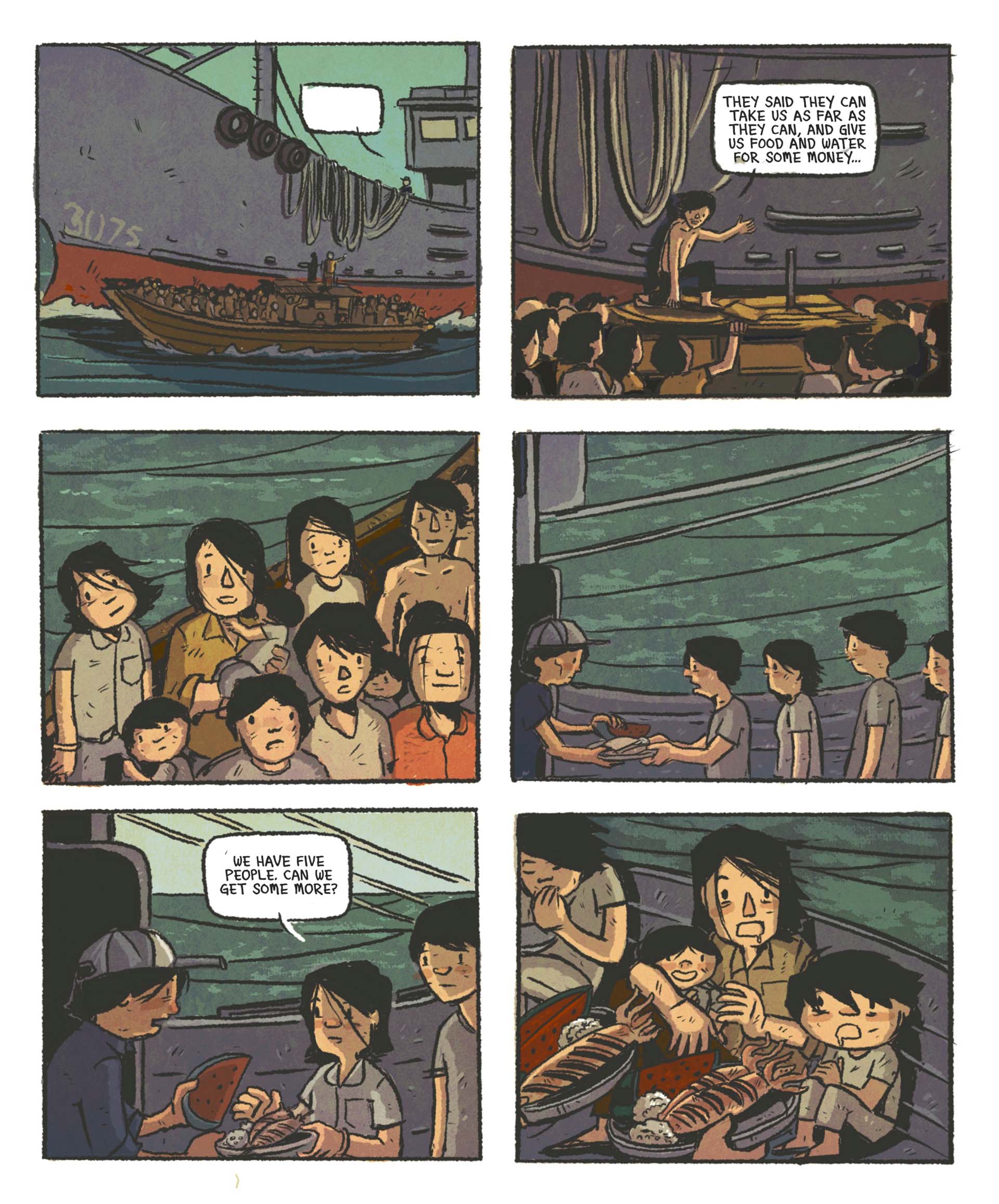

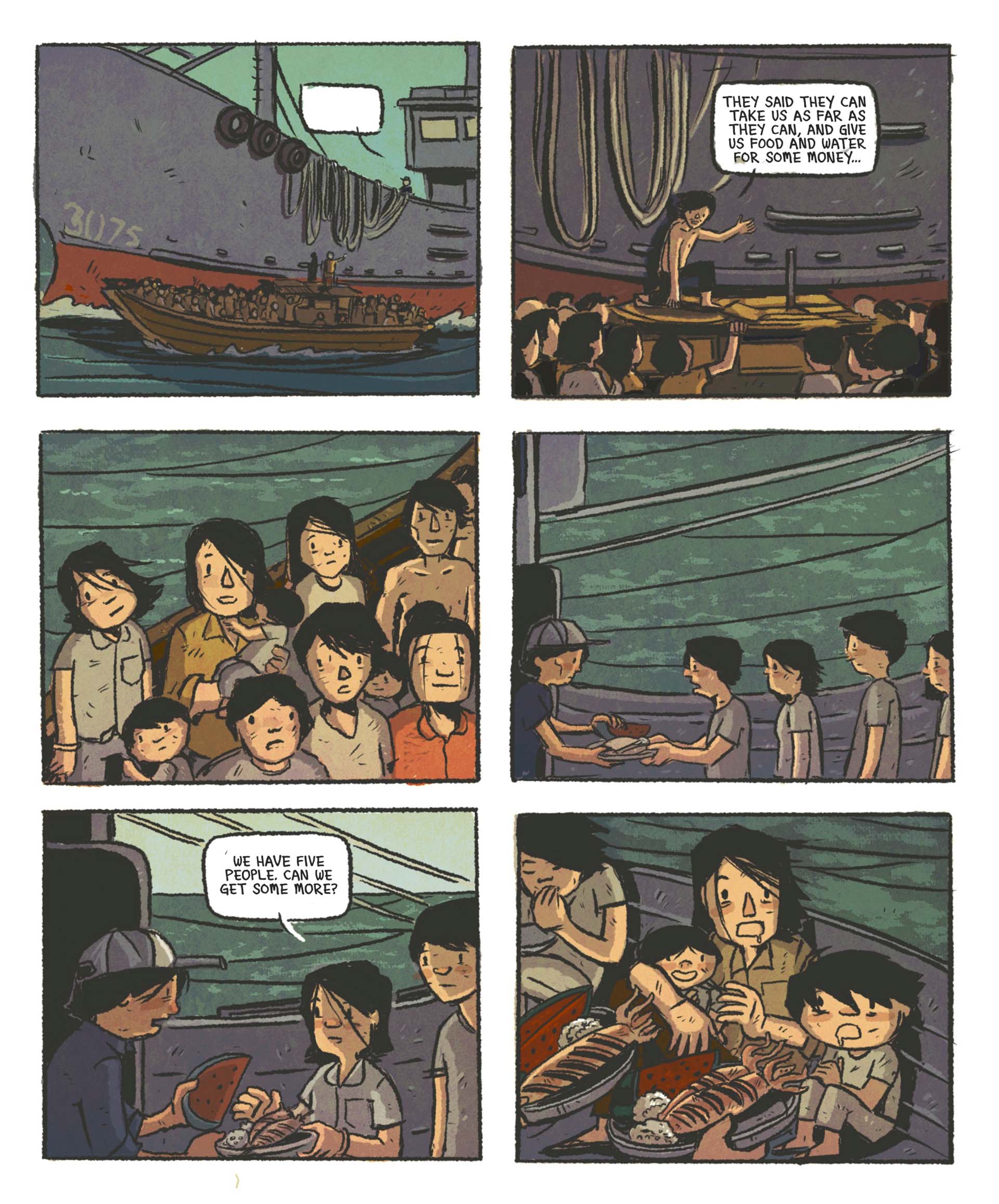

For example, something I thought was just fish sauce also had sugar and coconut soda and star anise. When I ate it I never picked up on those things. I realized how it mirrored our trip to America. My mom just says, “Yeah, we were on a boat and got here, and it was this and that.” But when you sit with the details, it’s like the nuance of a recipe with so much more happening. That made me realize that my parents were constantly trying to protect us when we were kids by making it look easy. Whether it’s not telling us about their hardships or making light of the work they did to provide dinner, they were trying to shield us.