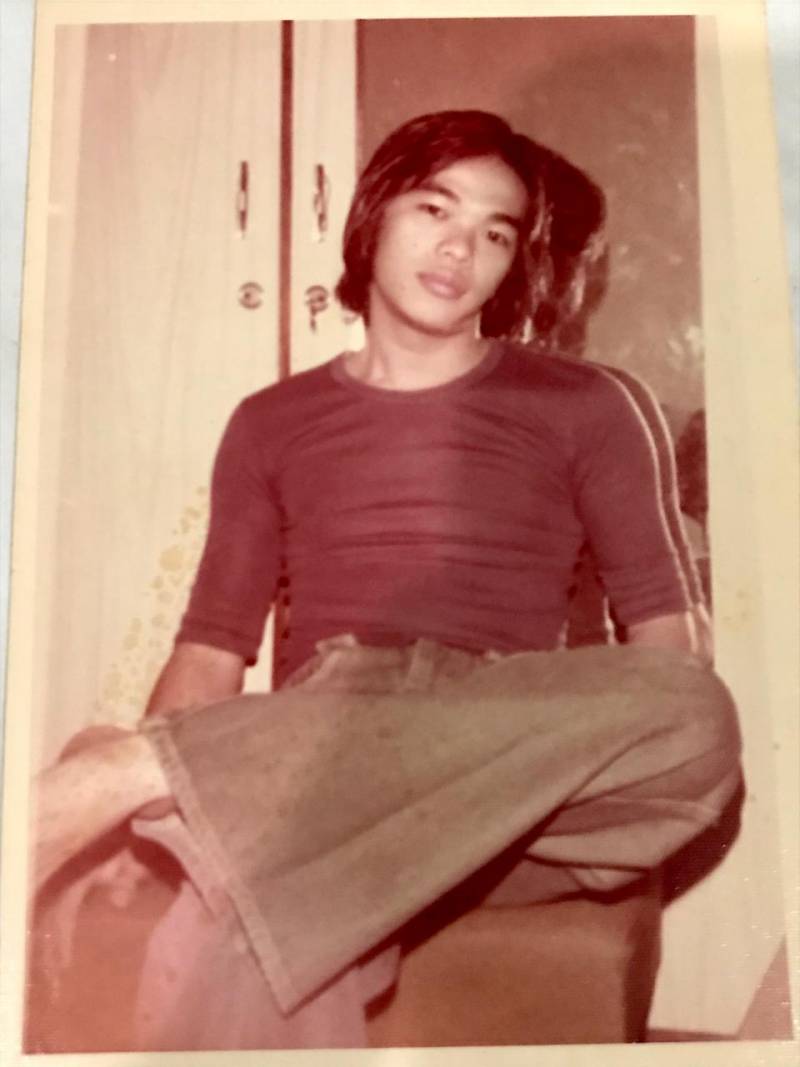

Bay Area resident Rachel writes in remembrance of her father Wahyu Lo. KQED is creating an online memorial to honor those who’ve passed due to COVID-19. If you have someone you’d like to pay tribute to, we invite you to share their story with us here.

My dad was a guy who enjoyed the simple pleasures in life. He grew up poor in the ghettos of Jakarta, one of 11 siblings. As a young man, he took a job on a remote island off of Java fixing televisions and other electronic devices for the workers that lived on the island and manned the offshore drilling rigs out at sea. Over time, he learned how to fix bigger and more important pieces of equipment for them and eventually, he began to offer general repair services for the oil and gas industry. With these humble beginnings, he grew what ultimately became a multi-million dollar business.

My dad met my mom, Fenty Wibowo, when they were in their early twenties and, together, they raised four children (Nia, Ady, Rachel and Maria). We kids can still remember living in a simple house with just a few rooms in the suburbs of Jakarta, riding three or four together on a motorbike through the city because that was our only mode of transportation. The four of us had the opportunity to go to college, live and work in the U.S., as well as travel the world and have experiences that would have been beyond the wildest dreams of our parents when they were our age.

Even with all his success, dad most enjoyed the simple things. While he owned beautiful houses, he preferred to spend his time at a place he called Ta-Kos, short for “Tanah Kosong,” which translates to “empty land.” Ta-Kos was empty land to begin with, a one-acre lot right in the middle of busy Jakarta, but dad turned it into a little sanctuary for himself. He built a small house of bamboo walls. Around the house he planted fruit trees that now supply at least a half-dozen varieties of mangoes among other things. He loved animals. Growing up we were surrounded by dogs, monkeys, chickens, parrots, iguana, ducks, turtles and many others; dad made it seem so normal. These days there are typically a dozen or more dogs running around the property. In addition to the house and garden, Ta-Kos also features a garage full of odd parts and projects in progress, a yard with an old boat over here, a defunct shipping container over there, and other odds and ends that might have been long since forgotten or just seemed like they might be useful someday.

Dad started coming down with some flu-like symptoms in early March and, while we urged him to go to the hospital given the growing pandemic, he insisted that it was no big deal and that he could just sweat it out working in his garden at Ta-Kos. My mom and little sister, Maria, eventually got him to check into a hospital. Unfortunately, the local health care system was already overwhelmed. Dad spent his last week in two different hospitals, where he was given a bed and some care. My mom, brother and little sister took turns around the clock just outside the room where he was quarantined with other sick patients.