California’s photographic history begins when California does. That is, when the state of California does (the land, its native people and their colonizers existed long before 1850, known by Ohlone and then Spanish names). But it was the Gold Rush, and the arrival of hundreds of thousands of prospectors—along with their diseases and dreams—that carried photographers west.

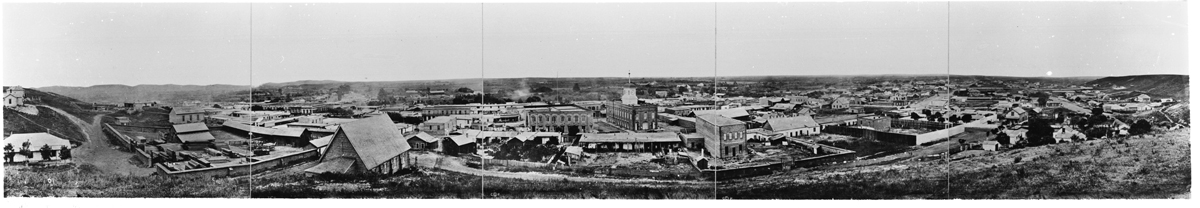

Boomtowns: How Photography Shaped Los Angeles and San Francisco, the latest exhibition at the California Historical Society, opens with a daguerreotype panorama from 1851 and closes with a gelatin silver print from 1949. Over that near-century, curator Erin Garcia groups images from California’s rival metropolises, charting the advances and setbacks in the growth of each city—and the key role photography played in selling ideas of these places to the rest of the country, as well as selling actual, physical land.

(It should be noted that San Francisco experienced most of the aforementioned setbacks, as it had a penchant for repeatedly burning itself to the ground.)

Boomtowns deftly underlines the power of photography to shape a city’s narrative and speaks to the importance of continually examining that narrative. Touring press around the exhibition, Garcia posed a series of questions that informed her curatorial approach. “Who are cities for?” she asked. “Why do they look a certain way? And who makes those decisions?”

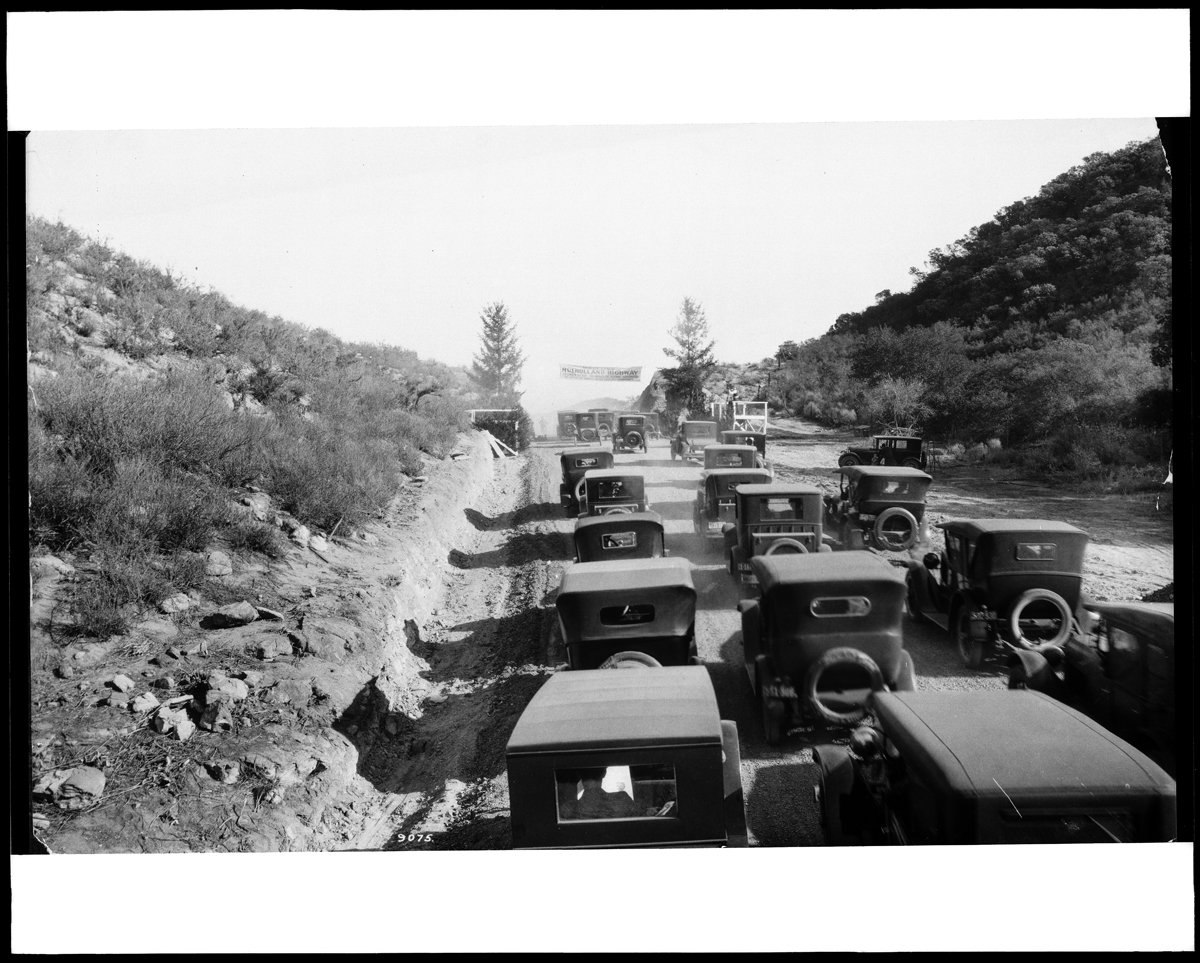

There are few people in the photographs of Boomtowns to answer that first question—the exhibition instead focuses on images of increasingly sturdy-looking buildings, roads and (especially in LA) highways, and the subsumption of the landscape into all of the above. More frequently, people appear in the margins, in descriptions of how these images were used. “California wants people like you,” reads the back of a 1911 photo postcard printed by Sunset magazine, advertising sunny Southern California living and cheap train fare to (white) recipients seeking to escape the cold, crowded and ethnically diverse cities of the East.