Trevor Paglen’s new show is called Impossible Objects, but the drawings, prototypes, and photographs on display at Altman Siegel document a project, that, while seemingly implausible, is very much real: he is putting a sculpture in space. This August, Orbital Reflector, a 100-foot-long, 6-foot-tall diamond-shaped object, will be fired into low orbit via a SpaceX rocket.

While the history of art is rife with astral intrigue, from the Russian avant-gardist Kazimir Malevich’s plan to reach the moon (years before the technology to do so was invented) to the “Light and Space” artists who engaged with NASA in the 1970s, there are few precedents to projects on the scale of Paglen’s. In our interview, he is quick to point out there are plenty of objects floating in space, but the few of them are artworks because, as he says repeatedly, “Space is really, really hard.”

Paglen is best known for his work examining military infrastructure — in distant photographs of CIA black sites, covert satellites, and landscape shots of internet cables. In recent years, he’s also developed a body of work using artificial intelligence to reveal the hidden biases of image classification algorithms. His work probes and inhabits the contradictions of mass surveillance by working within the structures he critiques. By launching his non-functional satellite from a military base, on a rocket with a spy satellite on top of it, Orbital Reflector may be the closest he’s gotten to working in tandem with those systems.

Near the front desk of the gallery is a scrappy charcoal drawing called View From Earth. A black square with tiny white dots and a star, it pays homage to Malevich’s famous Black Square painting, where the artist sought to express the underlying structures of the visual world (and in this case, the night sky) through abstraction.

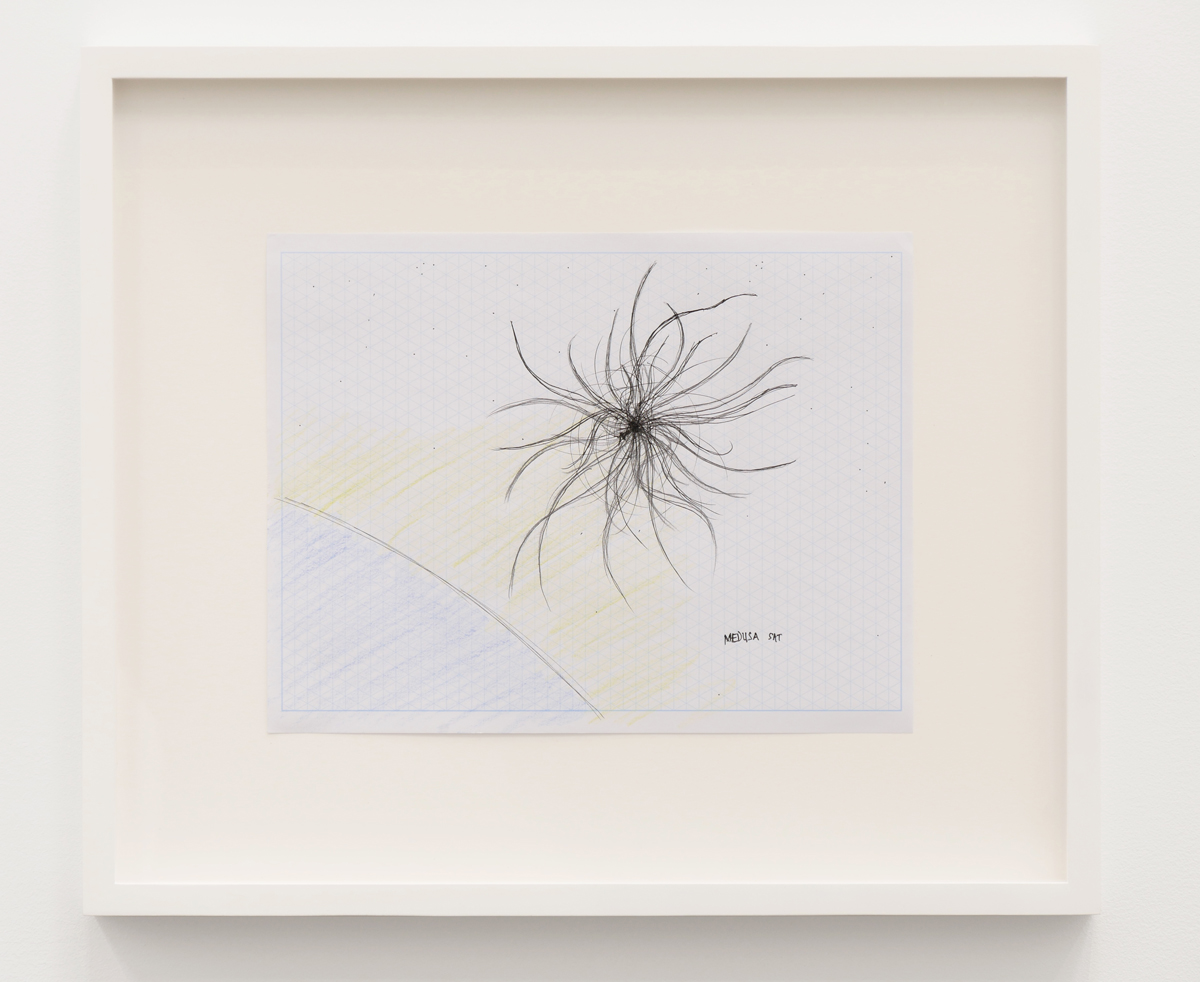

The exhibition begins with a series of photographs from Paglen’s ongoing series, The Other Night Sky, a project that follows and documents classified American satellites and other objects in orbit. Four of the images have their colors inverted, showing the charcoal lines of orbital paths against white backgrounds. “[The inversion] is the style that you use for more technical astrophotography,” Paglen says; it makes faint satellite paths clearer and highlights the aesthetics of the scientific style.