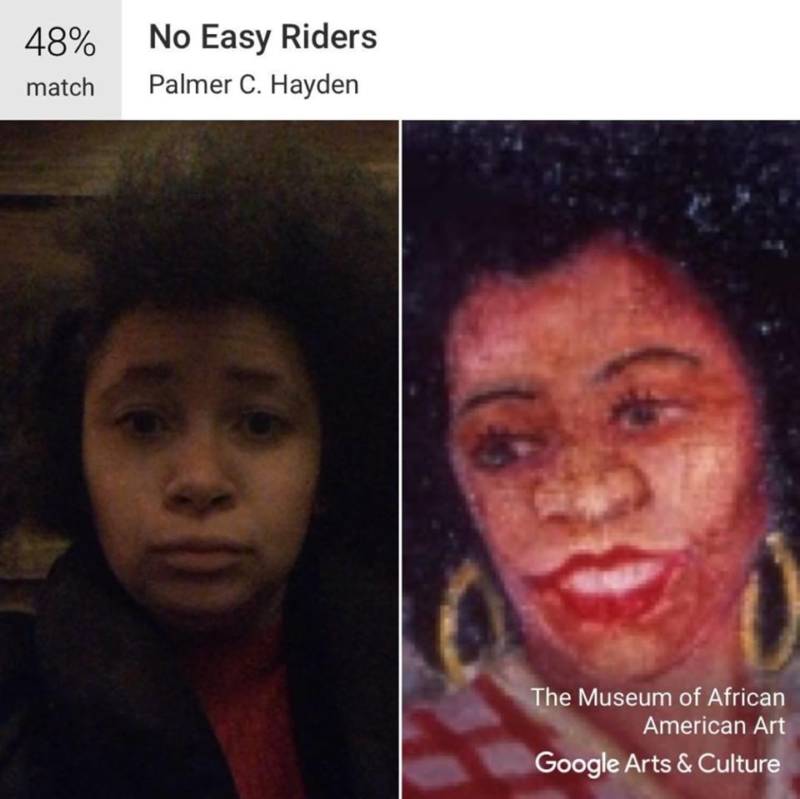

When an app asks you, “Is your portrait in a museum?” and you’re a person of color, it’s likely the answer is complicated.

Google Arts and Culture — Google Cultural Institute’s eager nod to art world institutions — released a wildly popular feature on their app this month that allows users to find their art doppelgänger.

Once you snap a selfie on the app, your “faceprint” is charted through a series of measurements (the distance between your eyes, the width of your nose, and fullness of your lips). Your image then goes through a matching process with over 70,000 works of art in Google’s database. The artwork candidates hail from powerhouses like the Louvre, J. Paul Getty Museum and Rijksmuseum on down to a handful of smaller art foundations and contemporary galleries.

If you’re looking for a complete list of artwork titles and origins, you’re out of luck. Intentional or not, Google has remained somewhat tight-lipped about the artwork they’ve cataloged.

Nevertheless, its source material is not exactly diverse. When I conducted a search of the 100 most recent posts tagged #googleartsandculture on Instagram, I found that 91 percent of the artwork was created by male artists, and 63 percent was created by European and American artists before the 20th century.