At the end of a rare appearance from Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries last week at the Asian Art Museum, an audience member asked the Seoul-based digital poetry pioneers what piece of literature has most influenced their work. Their matter-of-fact response: Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People.

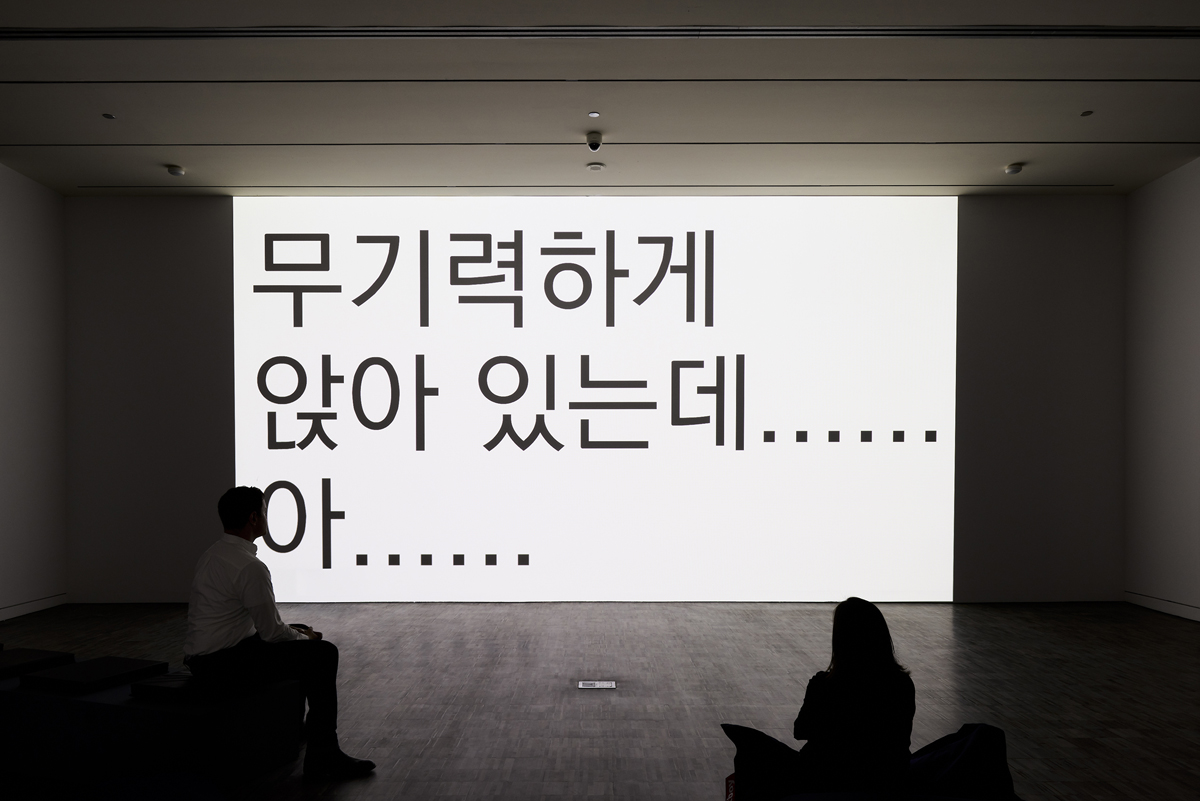

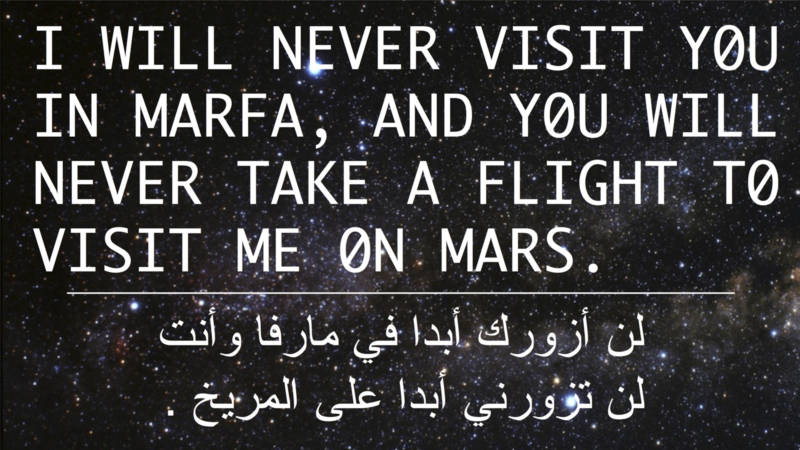

Like most of the elusive net art duo’s answers that night, the response was both unexpected and absolutely fitting. The duo (Korean Young-Hae Chang and American Marc Voge) makes Flash-animated poems that aren’t read so much as received. Most often appearing in black on a white background — and always in the font Monaco — their words don’t merely make up their poems, but perform them; pummeling you in quick succession, constantly changing sizes, and sometimes even trembling a little in place.

Each piece is synchronized to an original soundtrack (with some exceptions) that’s typically jazzy and percussive, with a world-music vibe that can’t quite be located on a map. But their work’s most mesmerizing characteristic is its tone. Often ending in exclamation marks, the statements feel urgent and propagandistic, demanding both attention and agreement. They’re sassy in both a self-deprecating and condescending way — and influential.

Seven of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industry’s durational poetry pieces (an hour’s worth, total) are on view at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum through Oct. 1 in a solo exhibition titled So You Made It. What Do You Know. Congratulations and Welcome!. According to the artist talk on opening night, when the museum tasked Senior Educator for Contemporary Art Marc Mayer with proposing a show earlier this year, he felt inspired to respond to President Trump’s “Muslim ban.” Young Hae-Chang Heavy Industries had recently finished a piece about the Syrian refugee crisis (the title of which eventually became the title of the exhibition), so Mayer and the duo began developing a collection of their pieces that would draw out themes of dread, power, freedom and xenophobia from their dynamic oeuvre.

Ah, arguably the most stirring piece in the bunch, starts off the looped projection, which fills two walls of an otherwise blank gallery — one wall showing English versions and the other playing Korean, Spanish, Swedish, Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese versions of the text (most of the duo’s works come in multiple languages). The narrative follows the internal monologue of a person who’s been pulled out of a line by men in uniforms to be questioned and ultimately detained — very similar to, if not explicitly the experience of someone being racially profiled by TSA agents. This ambiguity is what makes the piece provocative; it’s as much the possible recollection of an actual experience as it is a philosophical allegory.