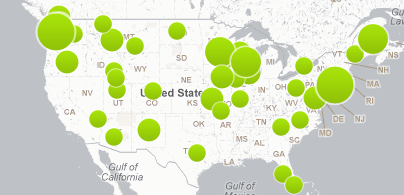

As the map illustrates, many areas in the country are in the grip of whooping cough outbreaks, everywhere but California. More on California in a minute. Let's first take a look at a new(ish) vaccine and see how its limitations might be contributing to the outbreaks.

In the 1990s, the U.S. and other developed countries switched from one kind of vaccine against whooping cough (also called pertussis) to another. The older vaccine was very effective but there were concerns about a rare side effect, a neurological disorder, which may (or may not) have been connected to the vaccine. More commonly, the vaccine caused the same minor side effects that we traditionally associate with shots: redness, soreness at the injection site, etc. Except that with the old pertussis vaccine, the side effects occurred more frequently.

In her wired.com blog noted science reporter Maryn McKenna recaps the research and wonders if there could have been an unexpected trade-off with this new vaccine -- that it is less effective and therefore contributing to the outbreaks we're seeing now. From McKenna's blog Superbug:

In the most recent research, a letter published Tuesday night in JAMA, researchers in Queensland, Australia examined the incidence of whooping cough in children who were born in 1998, the year in which that province began phasing out whole-cell pertussis vaccine (known as there as DTwP) in favor of less-reactive acellular vaccine (known as DTaP). Children who were born in that year and received a complete series of infant pertussis shots (at 2, 4 and 6 months) might have received all-whole cell, all-acellular, or a mix — and because of the excellent record-keeping of the state-based healthcare system, researchers were able to confirm which children received which shots. (NB: Queensland kids, like kids in the US, also receive boosters after the infant series, along with a final booster in their preteen years.)

The researchers were prompted to investigate because, like the US, Australia is enduring a ferocious pertussis epidemic. When they examined the disease history for 40,694 children whose vaccine history could be verified, they found 267 pertussis cases between 1999 and 2011. They said:

"Children who received a 3-dose DTaP primary course had higher rates of pertussis than those who received a 3-dose DTwP primary course in the preepidemic and outbreak periods. Among those who received mixed courses, rates in the current epidemic were highest for children receiving DTaP as their first dose. This pattern remained when looking at subgroups with 1 or 2 DTwP doses in the first year of life, although it did not reach statistical significance. Children who received a mixed course with DTwP as the initial dose had incidence rates that were between rates for the pure course DTwP and DTaP cohorts."

Even if the current vaccine is less effective than its forebear, McKenna makes clear that the vaccine is still highly valuable. Dr. Gil Chavez, state epidemiologist and deputy director of the department's Center for Infectious Diseases, concurs. "We are aware of reports of acellular vaccine being less effective," he told me in an interview. "From the onset of the use of these vaccines, we public health professionals try to weigh both safety and effectiveness. The new vaccines are very safe, so we, the public health community, went to that because of safety."

Which brings us back to the recent history of whooping cough outbreaks in California. While California is not suffering now, the Golden State had a fierce outbreak in 2010 -- 9,000 cases and nine infants died. In response, the state mounted a massive vaccination campaign for 11 to 18-year-olds. More than 97 percent of students enrolled in grades 7 through 12 were vaccinated during the 2011-2012 school year.