In the late 1990s, a new version of the whooping cough vaccine was introduced. The big benefit was that it had fewer side effects. But in the years since, evidence has been mounting that this newer vaccine loses its effectiveness -- and fast.

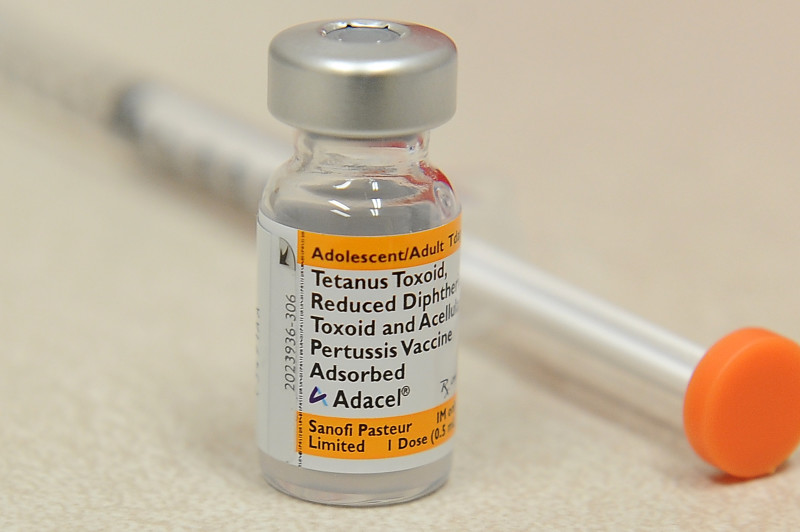

Now, another study sheds light on how well the "booster" dose works. California requires this booster -- called Tdap -- for all incoming 7th graders.

Researchers at the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center looked at the protection level of 175,000 adolescents in the Kaiser Northern California system vaccinated with Tdap. And just as with earlier studies, they saw that protection faded.

"What we found was the the Tdap vaccine offers moderate protection in the first year," said Dr. Nicola Klein, co-director of Kaiser's vaccine center, "but then that rapidly decreased over the next four years, so by the time we were at four years after vaccination, it was down to nine percent."

There have been two statewide whooping cough -- also called pertussis -- epidemics in recent years. The first was in 2010, the second in 2014, which was the first where all adolescents had received only the newer pertussis vaccine, the "acellular pertussis" vaccine: five doses by age 6, plus the booster before 7th grade. The 2014 epidemic was even more severe than the one in 2010.