In 2010 Broderick's group opened the state's first "teaching health center" -- the Valley Family Medical Residency Program. It has trained 12 doctors a year since then.

The teaching health center model is gaining traction. This summer, the Sierra Vista Family Medicine Residency Program will welcome its first four residents to Fresno. California's third teaching health center will be located in Redding.

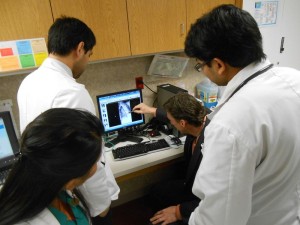

Still, traditional programs play a huge role in training the Central Valley's future doctors. UCSF-Fresno remains the largest provider of graduate medical education in the Valley, including 12 family medicine residents each year.

Gene Kallsen, the assistant dean of UCSF-Fresno, says the university and the teaching health centers share the goal of increasing the number of primary care doctors in the Valley.

But, Kallsen explains, UCSF-Fresno is blocked from growing its residency programs to meet the region’s needs for primary care doctors. A major one, he says, is a convoluted system that ties -- and caps -- the number of medical residents to the number of Medicare patients at a hospital. Once that cap is set, it can’t be changed.

“One of the barriers is that programs like ours can’t grow unless we identify new sites,” Kallen said. "We can only get federal funding for so many residents, and we live up against that cap.”

That’s where new programs, like the teaching health centers, come in.

“We’re not trying to compete with UCSF at all, and we don’t want to have that perception,” said Norma Forbes, the executive director of Fresno Healthy Community Access Partners. Her organization partnered with Clinica Sierra Vista to launch its Medicine Residency Program.

“This is a different model that we hope will grow the number of family medicine doctors," she says. "There is room for both types of training residents here in the Valley and across the country."

Forbes said the program follows a curriculum similar to more traditional family medicine residency programs. But residents at the teaching health center will gain experience with a variety of patients and procedures, instead of specializing in one specific type of medicine. She drew a distinction between the care offered at a large university hospital's outpatient -- or ambulatory care -- clinics and that of community health center's primary care clinics.

“Those primary clinics are free-standing and they are really focused on prevention and wellness -- and working with patients from birth to death," Forbes says."And when you get into ambulatory clinics associated with more urban environment hospitals, you run into the specialization.”

She is confident that the teaching health center model will help train more doctors who are dedicated to serving Valley communities and slowly remedy the region’s primary care doctor shortage. She hopes all of the program’s residents will practice in clinics in rural areas of the Valley after they finish their residencies.

“Our goal is to get 100 percent of them, all four of them (each year), staying right here, so we can truly increase the number of doctors through this residency program,” Forbes said.

The program currently has a three-year grant from the federal government.

Back at the teaching health center in Modesto, Dr. Broderick congratulated medical student Dr. Gewel de los Santos for helping a patient reach a healthy weight. She responded with outright enthusiasm.

Valley residents can only hope that more family medicine residents are as excited about practicing in the region.